“Steinbeck was normally permissive with his editors on such points, though he strongly resisted what he called ‘collaboration’ . . .”

In Book Marks, an occasional feature at Current, I take fresh cuttings from old books (or about old books). They are often about writing, education, communication, and the life of the mind generally, though I reserve the right to snap a sprig of greenery that simply tickles the fancy.

Why look at old books? Because there’s a slat loose in the fence they’ve got us penned up in, and we can jiggle it free to see better what’s going on out there.

With each extended quotation I offer an orienting comment, but that’s not where the action is. The question is whether the words of those long gone may speak to you.

*

The novelist John Steinbeck wrote East of Eden, arguably his masterpiece (“I think perhaps it is the only book I have ever written,” he once remarked), in an unusual way: He wrote it longhand in pencil on only the right-hand pages of an oversized notebook that his longtime editor at Viking, Pascal Covici, had given him.

Concurrently, on the left-hand pages of that same notebook he wrote a daily letter to Covici, building up over the year (roughly the whole of 1951) that it took to complete the first draft, a running journal of commentary on the novel, on the work of writing, and on himself. It’s a remarkable text in its own right, which Viking recognized and published in 1969.

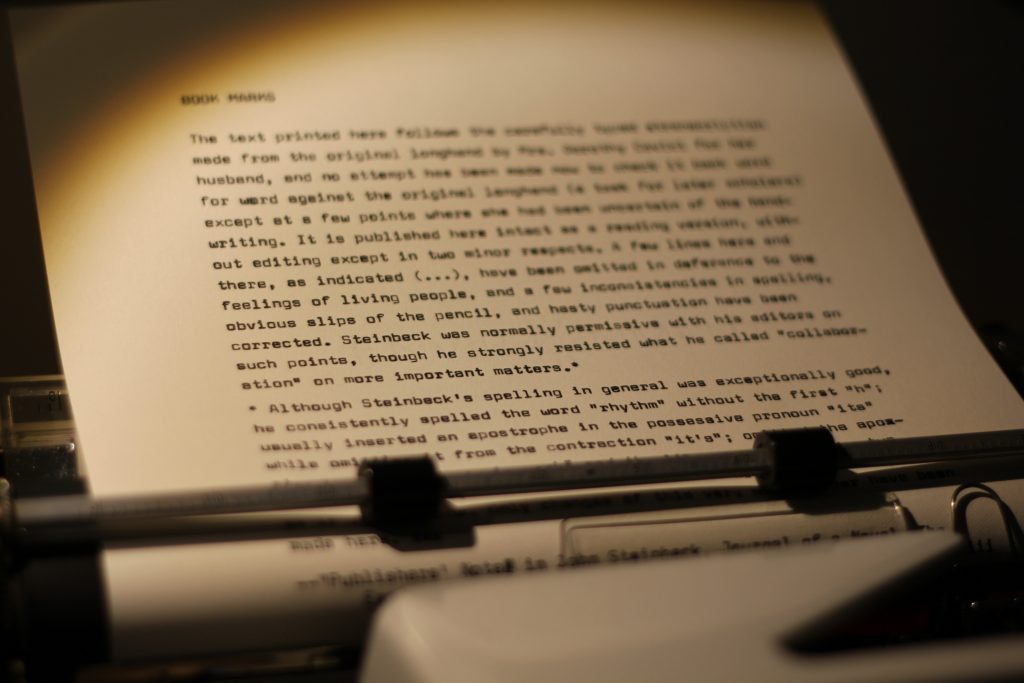

But that’s not what this Book Mark is about. Rather, it’s about a description from the book’s prefatory “Publishers’ Note” in which they describe their standards of transcription and editing, Steinbeck’s consistencies in spelling, and his permissiveness with or resistance to collaboration. Hear what the publishers have to say:

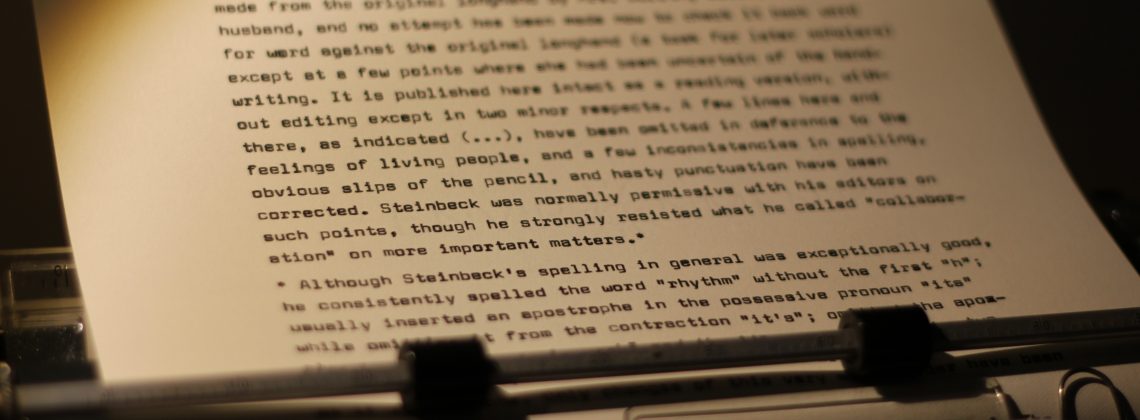

The text printed here follows the carefully typed transcription made from the original longhand by Mrs. Dorothy Covici for her husband, and no attempt has been made now to check it back word for word against the original longhand (a task for later scholars) except at a few points where she had been uncertain of the handwriting. It is published here intact as a reading version, without editing except in two minor respects. A few lines here and there, as indicated [. . . ], have been omitted in deference to the feelings of living people, and a few inconsistencies in spelling, obvious slips of the pencil, and hasty punctuation have been corrected. Steinbeck was normally permissive with his editors on such points, though he strongly resisted what he called “collaboration” on more important matters.*

* Although Steinbeck’s spelling in general was exceptionally good, he consistently spelled the word “rhythm” without the first “h”; usually inserted an apostrophe in the possessive pronoun “its” while omitting it from the contraction “it’s”; omitted the apostrophe from “the day’s work” and the like; tended to make two words of such compounds as “background” and wrote “of course” as if it were one. Only changes of this very minor order have been made here.

—”Publishers’ Note” in John Steinbeck, Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters (Viking, 1969; repr. Penguin, 1990), viii

I love reading about Steinbeck’s spelling idiosyncrasies. Delightful little details.

“Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters” is actually one of the books I’m reading right now. There are a lot of inisghts about writing sprinkled throughout among passing observations, novel talks, mundane details of life and invention schemes. A good read for anyone hoping to get a look behind the curtain (although he presents himself fairly consistently in the non-fiction he meant to publish).