Peter Jackson’s new documentary transports us back to a radically different age—one that feels strangely familiar

I’m a little embarrassed to admit how much time I’ve spent in the weeks since Thanksgiving re-listening to, reading about, and obsessing over the Beatles. Like so many other Americans, my family and I spent several days transfixed watching Peter Jackson’s latest filmmaking masterpiece, The Beatles: Get Back. The nearly eight-hour distillation of their storied twenty-two-day rehearsal/recording session in January of 1969 grants viewers the illusion of unfiltered access to the Fab Four’s creative process. Here they conceived, developed, rehearsed, and eventually performed seven or eight brand new songs, which formed the core of what would become their final album, Let it Be.

The cameras captured it all. It is magical.

From sixty hours of mostly never-before-seen video footage—filmed for a never-produced television documentary—along with another 150 of audio, Jackson meticulously restored, edited, and wove together a riveting narrative of creative energy, evolving friendships, playful waggishness, and the volatile trajectories of unrivaled global fame. Much could be said—and, of course, has been said —about Jackson’s project. It’s given us the rare gift of meeting the Beatles anew while breathing fresh life into longstanding questions about their final years: How did they work together? Was the music genuinely collaborative? Did their friendship survive? Did Yoko split up the band? And, of course, why did they stop performing live?

The band’s iconic forty-minute concert atop Apple Corps’ central London studios supplies Get Back with its thrilling and poetic climax. It was their first live performance in nearly three years. It would be their last. Jackson gestures to this fact near the documentary’s start in a brief synopsis of the band’s history. He focuses appropriately on their 1966 decision to end live performances and, functionally, withdraw from public view. Permanently. While there’s no simple answer to why they did so, Jackson highlights a culprit familiar to Beatles fans: John’s infamous Jesus quote.

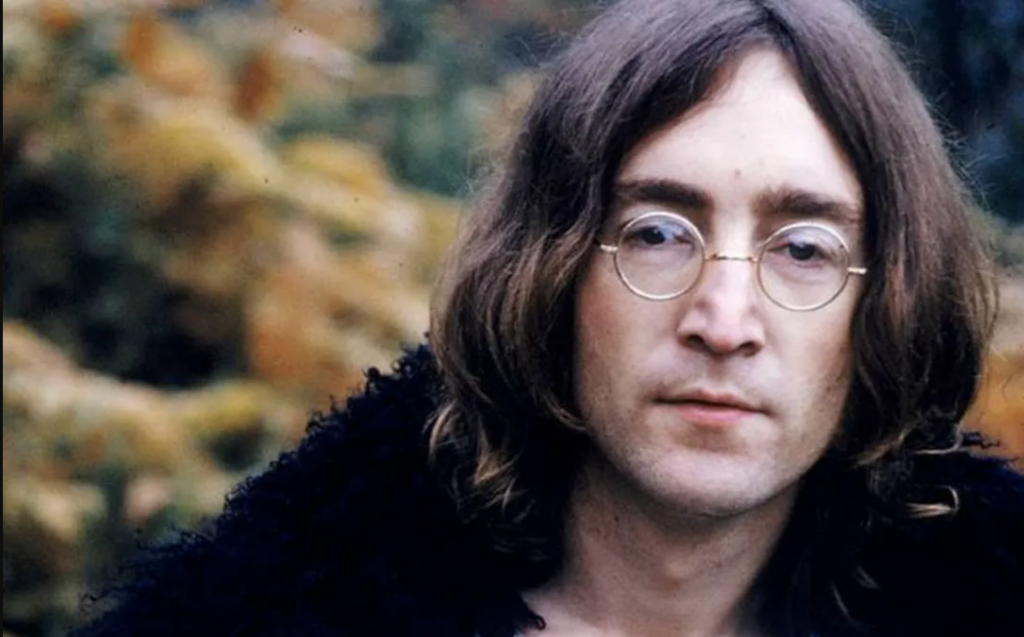

It seems I’ve always known that John at one point stirred controversy by declaring the Beatles “more popular than Jesus.” While the episode never struck me as more than a minor rumpus, the documentary suggests otherwise. In fact, Lennon’s comments and the American fallout may be among the most consequential events in the band’s existence. And a salient premonition of culture wars to come.

On March 4, 1966, the London tabloid Evening Standard published an interview with John in which the topic veered toward religion, a subject then consuming much of the eldest Beatles’ recent reading. In the notorious passage he would come to regret, Lennon stated, “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I’ll be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus right now; I don’t know which will go first—rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.” In the UK, Lennon’s blunt remarks caused no fuss or furor, a non-reaction widely interpreted as reflecting a nation already at peace with its own growing secularity. Their impact months later on American audiences would be starkly different.

It now seems quaint to think of information traveling abroad at a pace of months rather than seconds, but it took until mid-summer for Lennon’s remarks to gain popular notice in the U.S. Though republished in various American outlets in the late spring and early summer, it was the interview’s appearance on July 29 in the “Shout-Out Issue” of the controversy-courting teen monthly Datebook that sounded the national alarm. Copies of the interview spread quickly to radio stations across the country, especially in the South, fanning flames of anger and agitation wherever it went. Within a day or two, a nationwide movement arose determined to ban the Beatles from the airwaves and to urge the destruction of personal record collections and other band merchandise.

The band was set to launch an American tour on August 12, less than two weeks after the Datebook publication. Although failing at first to take the matter seriously, the band soon understood that the Jesus quote would consume them and their entire American tour. Newspaper editorials condemned the band as blasphemous and communist. Reporters continually asked the four to elaborate and clarify the meaning of John’s comments. Ex-Beatlemaniacs lined up to denounce their former idols, in some cases burning them in effigy. And resilient fans held screaming matches with emboldened detractors from coast to coast.

The day before the tour began, Lennon issued a formal quasi-apology. Insisting that he wasn’t comparing himself to Christ or trying to slander religious faith, Lennon reluctantly noted, “If you want me to apologize . . . if that will make you happy, then OK, I’m sorry.” Though his apology did little to dampen public outrage, the band managed to complete its fourteen-city tour. At each stop, they confronted lively protests, ongoing public denunciations, and growing threats of violence. Two performances in Memphis went on as planned despite a city council vote to shut them down: “The Beatles are not welcome in Memphis.” Someone hurled a lit firecracker on the Memphis stage while the band performed.

Everyone by 1966 knew the Beatles as a touring band. Jonathan Gould estimates that, since 1961, they had logged roughly 1,400 live performances worldwide. Following the Jesus-quote summer tour, they would perform publicly again only once more, the 1969 rooftop gig in London. The final brilliant years of the band’s existence are often and aptly described as reclusive.

It isn’t hard to argue that in August 1966 the Beatles’ most inventive and enduring musical output was still ahead of them. They would develop into far greater artists outside the public gaze than they were under its searing heat. But something about the Jesus-quote summer had unalterably changed the global phenomenon known as the Beatles. These cool and brazen poster boys of youthful rebellion crashed headfirst into the defensive ramparts of a still presumed Christian nation. And the once-beloved Liverpool mop-heads responded with retreat.

It’s sometimes tempting to treat the culture wars that now engulf our social and political lives as if they first emerged on a Manhattan escalator ride in 2015. We imagine that our deep political divisions and value-based differences are unprecedented. But the Beatles’ summer of 1966 reminds us that there’s nothing new about this kind of cultural warfare. The epic contest over American values kicked up that summer feels still irresolvable, and, as such, strangely contemporary.

That summer John Lennon the working-class artist exercised his free speech rights by deconstructing the pretensions of Western Christianity, exposing its hypocrisies and delusions. He and his mates were canceled by an angry mob of violent religious zealots.

That same summer John Lennon the elite artist arrogantly mocked and belittled the most cherished beliefs of his core audience in the American heartland. Those real Americans responded by exercising their rights of free speech, speaking out to protect their families and to preserve their heritage.

The ghost of culture wars future had pulled back the veil. A half-century later, what might that ghost be showing us today?

Jay Green is Professor of History at Covenant College. His books include Christian Historiography: Five Rival Versions and Confessing History: Explorations of Christian Faith and the Historian’s Vocation (edited with John Fea and Eric Miller). He is Managing Editor of Current.