The fading of a republic yields harbingers aplenty

On November 7, armed insurrectionists led by a disgruntled candidate who failed to win the recent election for chief political office planned to assassinate the leader of the state. They then intended to storm the senate house, assassinate multiple senators, and install their leader, thus redeemed, in what they saw as his rightful position of political authority.

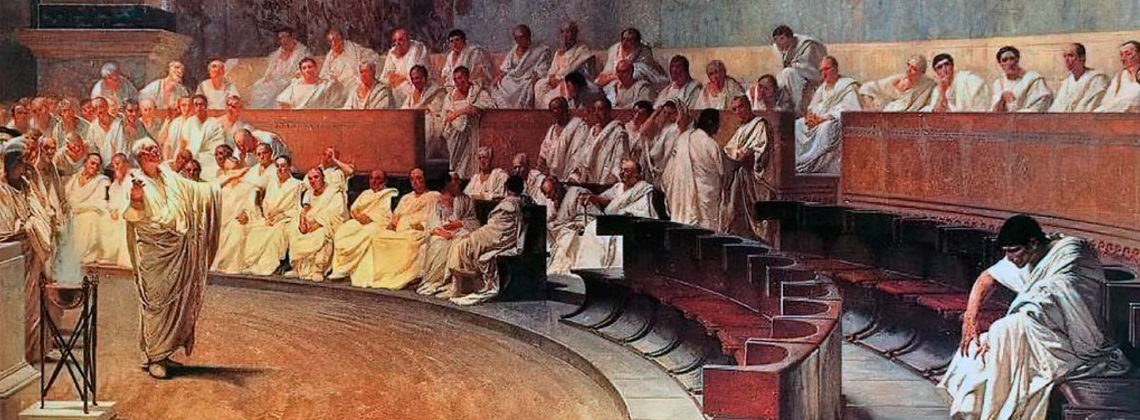

Or so, at least, wrote (and spoke) one of the chief targets of the coup, consul Marcus Tullius Cicero, in 63 BCE. Since antiquity Cicero’s four Catilinarian orations have been among the most widely known works of Roman literature. In his speeches Cicero reveals intimate details about the conspiracy, its leaders, and their aim of taking the republic by force.

But was Catiline’s conspiracy a true conspiracy? Or was the narrative of a grand conspiracy itself a hoax, a smaller crisis blown out of proportion by over-eager Cicero? So wondered some of Cicero’s opponents in later years. In 58 BCE, the plebeian tribune Publius Clodius Pulcher led the charge in turning public opinion against Cicero, whose acts as consul to suppress the Catilinarian conspiracy would eventually result in his exile from Rome.

On January 6, 2021, armed insurrectionists, egged on by a disgruntled candidate who failed to win the recent election for chief political office, stormed the U.S. Capitol building, where the Senate was meeting. They planned to assassinate multiple senatorial leaders and take over the political apparatus. But was this a true conspiracy? Or is the conspiracy narrative itself a hoax? Was all of this in reality a smaller crisis, deliberately blown out of proportion by over-eager liberal media? So ponders Roger Kimball, the editor of The New Criterion, in his recent lecture for Hillsdale College, published in the September edition of Hillsdale’s Imprimis. Although Kimball is not alone in asking this question, his speaking out on the subject as we near the first anniversary of the event reminds us that the past sometimes stubbornly refuses to stay in the past.

But what if both Clodius, the debonair aristocrat-turned-plebeian tribune, and Roger Kimball, the Ivy League-educated right-wing intellectual, are asking the wrong question? What if the real question is not whether the events in question involved a conspiracy or a hoax but rather what both the events and the continuing debates about them reveal about the health of a republic?

The Roman republic had not been well for a long time, concluded Sallust, writing about the conspiracy of Catiline in the late 40s BCE following another conspiracy: the assassination of Julius Caesar during a meeting of the senate on the Ides of March of 44 BCE, which effectively ended the Roman Republic. Sallust, once a promising politician and senator himself, turned to writing history as a consolation, a therapy of sorts, and an occupation to pass time after his political career had ended. In the process he invented the sub-genre of a monograph about a single war, and he wrote two of these: one about the conspiracy of Catiline, which Cicero suppressed so controversially, and another about the war with Jugurtha, the ally-turned-rogue king of Numidia.

In both works nostalgia for the bygone glory days of the Republic looms. The Roman character used to be so noble, Sallust laments—but look at it now! And this debasing of the Roman character Sallust blames for the fall of the republic through which he felt he was living. Around the time when Sallust was quietly sitting at home writing about the conspiracy of Catiline, Cicero met his end as part of the proscriptions of 43 BCE. Placed on the list of enemies of the state by Marcus Antonius for writing a series of fourteen virulent Philippics against him, Cicero was captured and beheaded shortly before he would have sailed off to yet another exile. Per Antonius’s request, Cicero’s head and hands were nailed to the rostra, the official location at which republican politicians once addressed the people. Few visuals as powerfully symbolize the end of the Republic and the free speech it once afforded its politicians.

In a vein similar to Sallust’s, David Barton and others rhapsodize about the founding of the American state as a noble Christian nation. Barton’s organization, Wall Builders, is determined to present American history as thoroughly Christian, attributing a deep faith to the founders. And it is that faith-based goodness and beauty of the original American state that the (nebulous) liberals have corrupted, and continue to corrupt, argue Eric Metaxas, Kimball, and David Barton, to name just a few.

Who are these “liberals”? Is one in fact either with them or against them? Or might there be a continuum? And what does it even mean to be a “conservative” now, anyway? Are denying that Donald Trump won the election and that the alleged “insurrection” of January 6 is just a liberal hoax two of the key criteria for distinguishing liberals from conservatives? Kimball, it appears, would say yes to the latter, at least.

In reality, conservative and liberal are shifting and confusing categories, as the original liberals and conservatives—the Populares and Optimates of the late Roman Republic—remind us. On that fateful day in the senate in 63 BCE, when Cicero first accused Catiline and his fellow-conspirators of plotting to assassinate so many senators and overthrow the republic, the liberal popularis Caesar spoke in favor of imprisoning the conspirators rather than executing them, Sallust tells us; in fact, Sallust provides what he claims was Caesar’s speech itself. On that day it took Cato the Younger’s solid and staunch conservatism to convince the senate that the death penalty was the only suitable punishment for treason. And yet, Cato would spend the rest of his political career promulgating a number of ethically grey measures, showing that in the Roman Republic, as in the American one, the labels sometimes do not matter, and politicians, liberal and conservative alike, are deeply fallible people.

Less than twenty years later, in April 46 BCE, Cato committed suicide in Utica as his final act of defiance against those who, he felt, were destroying the Republic. With the senatorial army’s opposition defeated, Caesar won that round of civil wars, not knowing that he himself would die less than two years later in the hands of another senatorial conspiracy. The history of the final decades of the Roman Republic abounds in such poetic yet tragic plot twists. For a country as politically divided as ours, these plot twists are apt reminders that events like January 6, 2021 are not one-time blips but are instead liable to be repeated.

The American state no longer is a republic, claims Kimball. On this point alone we agree.

Nadya Williams is Professor of Ancient History at the University of West Georgia.

Nadya Williams is the author of Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan Academic, 2023), Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic: Ancient Christianity and the Recovery of Human Dignity (forthcoming, IVP Academic, 2024), and Christians Reading Pagans (forthcoming, Zondervan Academic, 2025). She is Managing Editor for Current, where she also edits The Arena blog, and Contributing Editor for Providence Magazine and Front Porch Republic.