Young evangelicals are abandoning Christianity with increasing frequency. Are sites like Current nudging them toward the exits?

Early this summer Kevin Max, a founding member of the Grammy-winning Christian rap trio DC Talk, announced that he no longer considers himself a Christian. He stated that his decision came after a decades-long process of “deconstructing” his faith. Max became only the latest in a growing collection of high-profile figures to deconvert publicly, including Hillsong worship leader Marty Sampson, Desiring God contributor Paul Maxwell, singer Audrey Assad, Hawk Nelson’s Jon Steingard, and pastor and I Kissed Dating Goodbye author Joshua Harris. To name a few.

And these celebrity believers aren’t alone.

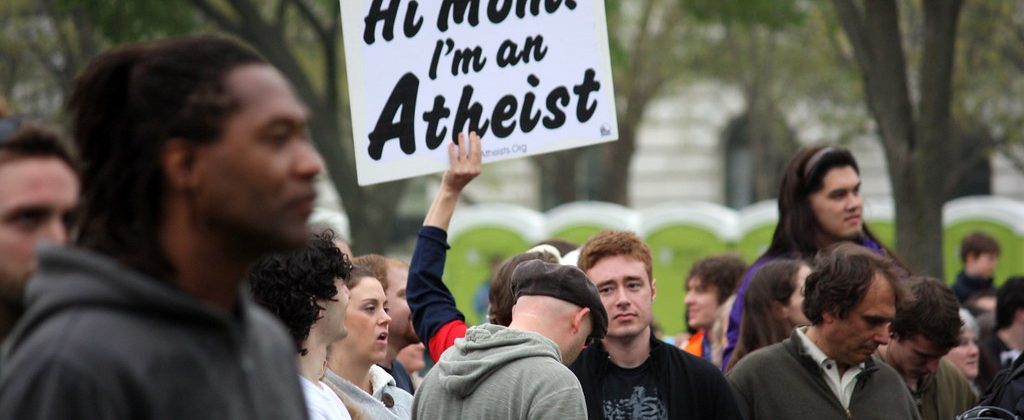

Over the past several years, a rising number of (especially) Millennial and Gen Z Christians have taken to social media to disavow the evangelical beliefs of their youth. A peek at YouTube reveals dozens (maybe hundreds) of “deconversion” and “deconstruction” stories that express a range of probing doubts about Christianity’s truth claims, often accompanied by heartbreaking stories of abuse, duplicity, and trauma experienced within varied evangelical settings. These frank, often soulful testimonies question, critique, reprove, and ultimately renounce the tenets of a faith once vocally and joyfully professed.

Meet the Exvangelicals.

A leading spokesman (and host of a podcast by the same name), Blake Chastain, considers Exvangelicals a diverse lot united only by what they have rejected. They elected to leave what Chastain calls the “totalizing mental and social environment” of evangelical Christianity, exchanging it for a liberating brand of “moral and religious autonomy.” Even so, Chastain is quick to lay down what he sees as a few non-negotiable commitments all share: “We embrace the LGBTQ community fully, are thoroughly feminist, denounce the role of white supremacy in society in general, and white evangelicalism in particular.” (It seems that giving up on the idea of fundamentals is easier said than done.)

In breaking with traditional Christianity, members of this movement (if that’s the right word) have indeed landed in various places philosophically. Some have shifted quickly to unalloyed atheism, while others express highly personal, non-institutional varieties of spirituality. Still others retain the label “Christian” while gravitating toward its most progressive expressions. One finds limited talk of theology among these Exvangelicals apart from repudiating the “rigidity” and “literalness” of evangelical faith. The paradigm shifts they have undergone seem more sociological than theological; more concerned with cultural claims than metaphysical ones.

What appears to drive Exvangelical passions most are deep frustrations—or, more often, embittered anger—toward the cultural tone, political posturing, moral stances, and innumerable hypocrisies they observe in the American evangelical subculture. Nearly pervasive concerns for justice and equity on matters of race, sexuality, and gender identity could no longer be squared with an evangelical culture increasingly tethered to the values of a contemporary Republican Party they consider regressive and corrupt.

Disappointment, aggravation, and rage against the many foibles and hypocrisies found among Christian believers are not a new phenomenon. They are as old as Christianity itself. And, at least since the Enlightenment, public renunciations of personal faith aren’t especially novel either. But the tenor and contextual specifics driving this recent spate of deconversions give this moment a unique feel. I believe the current wave of evangelical defections signals a kind of inflection point for conservative Christianity in America, where a distinct set of moral, cultural, and political vexations are directly fueling personal decisions to abandon the faith, especially among younger Christians.

For me, the Exvangelical phenomenon places our work at Current in an awkward and challenging position. While we cover a wide range of contemporary topics, it is no secret that we give a lot of attention to American evangelicalism, and the spotlight it receives here tends to be sharply critical. John Fea’s blog has long been an established and trusted source for news and commentary about American evangelicals and, again, the picture it paints rarely puts them in a flattering light. It is hard to avoid the brute recognition that the varieties of analysis and commentary published on this site supply fresh kindling for the already smoldering flames of Exvangelical cynicism and bitterness.

Let me be clear. Current is not an evangelical publication. It is not even a religious one. We are happy to publish writers from any and every perspective, whether religious or non-religious. We would just as happily publish pieces by individuals who claim the Exvangelical label. (Pitch us here.) Our commitment to free and open dialogue is intrinsic to our vision for Current. However, as we have indicated elsewhere, the editors of Current are, in fact, evangelicals. We worship at evangelical churches, teach at evangelical colleges, are committed to the historic Christian missions of our schools, and care deeply about the faith of our colleagues, students, and alumni. Many of the writers who publish essays and commentaries about evangelicalism on this site share these convictions and concerns.

I do not highlight this tension and my own ambivalence about it in order to apologize for our coverage of American evangelicalism. Far from it. Rather, I do so to acknowledge the dilemma this coverage poses for those of us who are motivated to pursue our brand of “warts-and-all” truth-telling out of a love for Jesus and his Church.

There is a serious and vital tradition in the human sciences of evangelical scholars who have devoted their professional lives to exploring the patterns and practices of evangelicalism. And the results have sometimes been disappointing, shocking, and even heartbreaking. Along with John Fea, writers like Jemar Tisby, Beth Allison Barr, and Daniel Williams, alongside journalists like David French and Michael Gerson, shine an uncomfortable light on past and present practices of conservative Christians. While far from perfect, this tradition of critical scholarship is rooted in caution, honesty, and nuance. But it’s also a part of a much older religious tradition of prophetic truth-telling that aims at repentance and reform.

Attending to and exposing ugliness found among brothers and sisters within our own communions is a sensitive but significant kind of noticing-the-log-in-our-own-eyes exercise, which is a vital feature of Christian faithfulness. We take that seriously. Among those who engage in this kind of work the temptation to join the ranks of the Exvangelicals is admittedly real. And more than a few have surrendered to it. Just as there is power in faithful Christian witness, a tarnished witness has consequences.

But I must continually remind myself that observing the broken practices of deeply flawed believers—my own especially—bears no necessary implications for the validity of Christianity’s truth claims. In fact, they remind us of our great need for a Savior. I hope my Exvangelical friends will contemplate this truth as they observe my own weaknesses and flaws, along with those among my larger evangelical family.

Jay Green is Professor of History at Covenant College. His books include Christian Historiography: Five Rival Versions and Confessing History: Explorations of Christian Faith and the Historian’s Vocation (edited with John Fea and Eric Miller). He is Managing Editor at Current.

Jay Green is Professor of History at Covenant College. His books include Christian Historiography: Five Rival Versions and Confessing History: Explorations of Christian Faith and the Historian's Vocation (edited with John Fea and Eric Miller). He was Senior Editor at Current.