What do contemporary Christians living in America have to learn from Christians around the world experiencing actual persecution?

Each Sunday my church prays for people across the globe who face ostracism, imprisonment, and even death because they are Christians. The social and political costs of practicing Christianity are especially high in places like Somalia, North Korea, Eritrea, Afghanistan, and Sudan, to name just a few, and the number of people who daily suffer for their faith seems to be rising.

Praying for globally persecuted Christians is a good discipline for our congregation. It helps us see the power authoritarian leaders exert in suppressing democracy, trampling liberties, and weakening the institutions necessary for civil society. But such prayers are also important for reminding us that persecution isn’t just an unfortunate biproduct of the Christian story. It is one of Christianity’s central and theologically necessary features. And it is real.

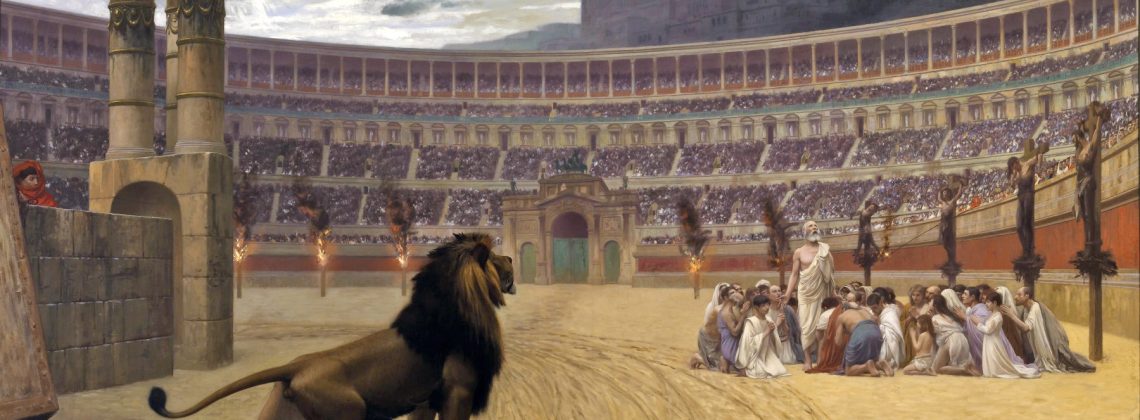

The earliest followers of Jesus navigated the ancient world as a fledgling sect within a barely tolerated minority religion in the vast Roman Empire. Centuries before Christians learned what it could mean to wield political power, marshal armies, or command majority populations, they experienced the world as a lowly, rag-tag bunch of subjugated peons, regularly victimized, imprisoned, tortured, and murdered.

The New Testament scriptures give voice to this spirit. In his first sermon recorded in Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus anticipated persecution for his followers, audaciously calling future recipients “blessed.” Jesus of course suffered and died in a very public way, forging a path of poverty, torment, and martyrdom for those who would “take up their crosses” and follow. Walking in the way of Jesus would mean experiencing a life on earth marked by over-againstness. “If the world hates you, keep in mind that it hated me first.”

The story of Christianity is indeed punctuated with episode upon episode of believers facing abuses, assaults, and agonizing deaths. (Let’s set aside for our purposes here how much this story is equally punctuated by Christians causing abuses, assaults, and agonizing deaths.) The Apostle Paul—himself an erstwhile persecutor—would become one of Christianity’s chief sufferers: imprisonment, beatings, hunger, exposure, and, ultimately, state-sponsored execution. Many others would follow. From Saint Peter to Saint Lucy, from Lazar of Serbia to John Huss, from Jim Elliot to Oscar Romero, exclusion, loss of liberty, and death have been staples of Christian faithfulness.

It is therefore no stretch or distortion to describe persecution as an essential feature of Christianity’s meaning and message. It is fully baked into the cake, and it has been from the beginning.

Regarding persecution, we might expect to find the brightest lights shone on Christians living under Islamist and other authoritarian regimes on the far side of the world. And there is no shortage of such examples! But the persecution that commands our greatest attention involves Christians living within the oldest, the freest, and most Christian democracy in the whole world: the United States of America. In other words, American Christians are obsessed with the persecution that they themselves are supposedly experiencing, or at least the specter of persecution that is lurking around the corner IF WE ARE NOT VIGILANT IN STANDING AGAINST IT!

In American politics, historian Richard Hofstadter described this tendency as “the paranoid style.” The Christian writer Alan Noble has called it the “evangelical persecution complex.” It assumes that vast impersonal forces or perhaps cabals of sinister elites are conspiring to suppress our freedoms, to undermine our faith, and to thwart our virtue. American Christianity, we assure ourselves, is always embattled and forever standing on the precipice of destruction. A single puff (or the election of the wrong presidential candidate) will surely extinguish it forever!

This tendency isn’t new. It’s been around throughout American history in one form or another, though the specific threats to faith and liberty are ever changing. Several such threats that have dominated the Christian imagination since World War II include Communism; Racial Integration; Removing Prayer from Public Schools; Women’s Liberation; Abortion Rights; The Gay Agenda; Secular Humanism; Teaching Biological Evolution; Islamic Sharia Law; and Marriage Equality.

At first glance, this appears to be simply a list of culture war issues that have mobilized the Christian right over the years. And it is. But the problem I’m describing isn’t the issues themselves. At least some of them have been genuine concerns worthy of resistance. The problem is the catastrophic rhetoric that nearly always accompanies the raising of these issues, persuading Christians that persecution looms just around the corner. Obsessive alarm and fear-stoking over critical race theory and transgender bathrooms are recent cases in point.

Stolen valor is a term used for imposters who falsely claim to have served in the military or wear unearned military awards or medals. Such imposters seek the glory and praise that justly goes to those who sacrifice and suffer without having done a shred of sacrificing or suffering themselves. It is a shameful, dishonorable form of fraud and, since 2013, a federal crime.

I have come to think of American evangelical claims of persecution amid the comparatively low stakes of our culture wars as a form of stolen valor. That isn’t to say these issues aren’t important or even vital. Some of them reflect serious concerns. They just don’t come close to the impending specter of persecution. And persecution is too theologically important to trifle with as we too often have. The easy evangelical adoption of the language of persecution in reference to our political slights and defeats cheapens its theological meaning for those who face the real thing day after day.

One New Testament writer summed up the difficult road that current and future Christ followers would travel. It is a challenging road that none of us should pretend to walk, living as we do within the relative comforts of our American middle class lives. “Some faced jeers and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment. They were put to death by stoning; they were sawed in two; they were killed by the sword. They went about in sheepskins and goatskins, destitute, persecuted and mistreated— the world was not worthy of them.”

Indeed, we are not.

Jay Green is Professor of History at Covenant College. His books include Christian Historiography: Five Rival Versions and Confessing History: Explorations of Christian Faith and the Historian’s Vocation (edited with John Fea and Eric Miller). He is Managing Editor at Current.