If recent research is right, politics and religion are even more tangled than we tend to believe

January 6, 2021: A shirtless man in a horned hat, his face painted in red, white, and blue stripes, struts across the senate floor. “F*ckin’-A, man! You guys are patriots!” he exclaims as he walks past others who are examining papers on desks. He points to a man lying on the floor in front of the Senate dais, blood trickling down the side of his face from a rubber bullet wound. “Look at this guy . . . covered in blood. God bless you, man.”

Minutes later, this same excitable man removes his horned cap in reverence as he leads other men in the chamber, via megaphone, in a communal prayer. “Thank you Heavenly Father,” he begins, “for this opportunity to stand up for God-given unalienable rights. . . . Thank you divine, omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent creator God for filling this chamber with your white light and love. . . . and for filling this chamber with patriots that love you and that love Christ.”

These scenes played out in a video recorded by a New Yorker reporter who followed Capitol insurrectionists into the Senate. The footage, ultimately used as evidence against the insurrectionists, presents a haunting picture of one of the strangest and most disturbing moments in American political history. That a group of violent men, some claiming that they came to hang the Vice President, would choose to stop and pray in the name of Jesus, presents us with a question: What does Christianity, or religion in general, have to do with what occurred on January 6?

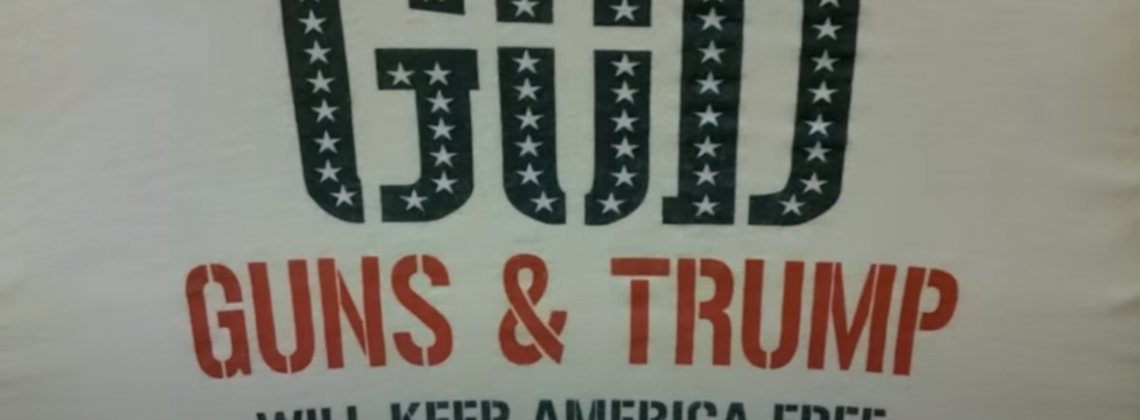

Some may ask how a group of self-described followers of Jesus could feel called to engage in violent insurrection. Here’s perhaps a better question: How did a group of men who were willing to violently stop an election outcome also see themselves as followers of Jesus? Is it always religion that influences our politics? Or is it possible that politics influences and even becomes our religion? Considering the recent scholarly work on American politics and religion, I suggest that religious identity in the United States is often downstream from political identity.

Most research on religion and politics assumes that religious ideologies are “upstream” from political beliefs: It is religion that shapes one’s politics, this thinking goes; people are religious first and political second. If America’s evangelical Christians associate with the Republican party, it is because the Republican party supports policies conservative Christians consider to be important.

This makes sense if we assume that religion is the identity that drives people’s social behavior. And in many ways religious belief does affect politics. Religious affiliation can affect everything from an individual’s level of civic engagement to the policies they consider most important when picking candidates.

But in her book From Politics to the Pews: How Partisanship and the Political Environment Shape Religious Identity (2018), Michelle Margolis argues that assuming it is religion that influences individual political beliefs is too simplistic. She presents a “life-cycle theory” of religious affiliation. Drawing from work in sociology, political science, and psychology, Margolis suggests that the timeline of the average American’s evolving relationship with politics and religion is backwards from what most work on the topic would insinuate. Individuals do not have a univariate relationship with religion. Many American teenagers question or leave their faith in their late teens and early twenties. Usually, those adults who do continue in their faith return to more consistent religious practice only after they have grown older and often when they have started to raise children.

This growing line of research suggests that Americans develop political beliefs and affiliations as a result of their experiences in adolescence. Living through crises, scandals, wars, and major political changes has a psychological effect that can influence a teenagers’ political leanings for most of their adult lives. By the time a person is old enough to raise a family, they are likely to hold to a certain set of political beliefs based on their experiences with politics while growing up.

Margolis uses US survey data to track religious attendance and political affiliation over time. Her findings suggest that the life-cycle theory is largely correct. Americans become less religious in their adolescence and young adulthood, but then a portion of those same individuals return to a more consistent religious practice, including weekly church attendance, belief in God, and belief in the power of prayer. Others make the decision to not return to church. Margolis finds that in the United States, political affiliation—identifying as a Democrat or Republican—has an effect on whether these individuals return to religion when they are older. Young adults who identify as Democrats are less likely to return to church when they are older compared to young adults who identify as Republican. She makes this case with multiple sets of surveys while also controlling for other demographic variables that might impact religious affiliation. In other words, there is evidence that Americans take their religious cues from their political affiliations.

What does this mean?

Margolis’s point is that we underestimate the power of partisanship on social choices. It is possible that the events of January 6 are less an indictment of the power of religious belief to lead people to act irrationally than a moment that highlights how politics itself can hijack the way Americans view religion.

In light of this research, along with what I saw in that video, I find myself reexamining my own social decisions. Do I choose where I go to worship, who I get coffee with, and who I associate with more because of my faith or because of my politics? The answers to such questions may not leave one comfortable, but they are a necessary place to start in unpacking the relationships between the political, the religious, and the social.

It is also well to consider that although society is often described as a divided set of systems and spheres of power (the religious, the political, and the economic are different systems that interact through various institutions), at the personal level these “spheres” are not so easily separable. Experiences help us form coherent stories about the world around us. Political and religious ideas can easily reinforce each other, influencing how we behave and what we do. Our identities are fluid in a way that institutions are often not able to reflect accurately.

If I walk into an American church on any given Sunday, I might well hear words that echo the horn-hat man: “Thank you divine, omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent creator God for filling this chamber with your white light and love.” That these words were spoken in the name of Jesus in the evacuated Senate chamber over a bloody man, hurt from a rubber bullet, should force us to reconsider what drives our beliefs and decision making. January 6 was not a one-off event. It should issue a caution to all of us: Maybe we don’t really understand how we’ve come to believe what we believe and say what we say.

Henry Overos is a PhD student at the Department of Government and Politics in the University of Maryland College of Behavioral and Social Sciences. His research focuses on the role of historical legacies on current-day politics, advances in computational social science methods, and the intersection of religious identity and democracy. He currently works with the Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Computational Social Science at UMD.

Henry Overos is a PhD student at the Department of Government and Politics in the University of Maryland College of Behavioral and Social Sciences. His research focuses on the role of historical legacies on current-day politics, advances in computational social science methods, and the intersection of religious identity and democracy. He currently works with the Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Computational Social Science at UMD.