Dueling historical narratives have long been at work in our midst. Only one is on the side of the angels.

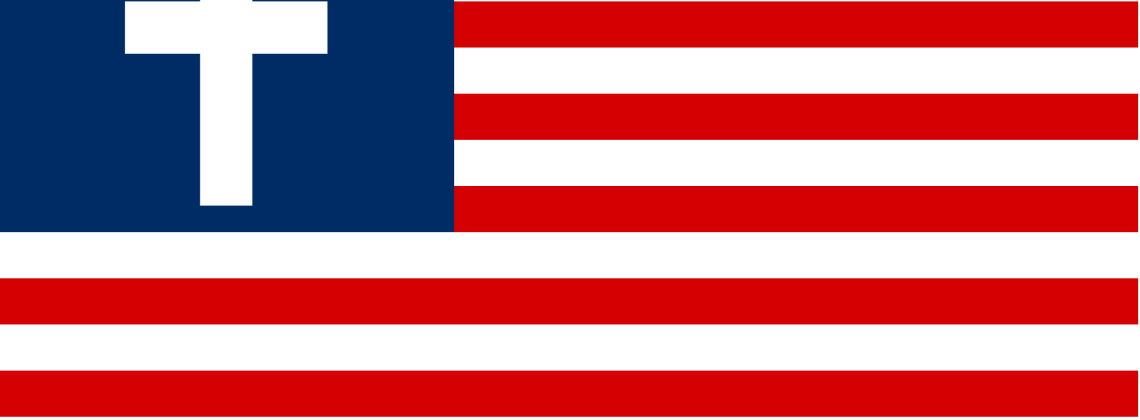

Photos of the Capitol Insurrection in early 2021 showed a perplexing variety of symbols: Christian crosses and wooden gallows, Trump flags and Gadsden flags, Crusader costumes and militia outfits. But where many secular observers only saw confusion, some scholars of religion saw the underlying unity: White Christian Nationalism.

Before the 2016 elections, there was little discussion of Christian Nationalism outside academic circles. During the Trump Presidency the discussion seeped into Christian circles. And after the Capitol Insurrection it garnered widespread media attention.

With attention comes contention.

To many Christian conservatives, “White Christian Nationalism” sounds like a left-wing smear: an accusation of racism affixed to their religion, joined with a sneer at patriotism. For some secular progressives, it merely confirmed their longstanding conviction that religion has no place in politics.

Both views are mistaken. White Christian Nationalism is an old and powerful current within American Christianity. But radical secularism is not the only alternative. There is a third tradition of political theology in the United States, a different understanding of its civic creed. It is a middle way that some call “American Civil Religion.”

White Christian Nationalism and American Civil Religion are not the same.

White Christian Nationalism is best understood as a historical narrative: “America was founded as a Christian nation; the founders were orthodox Christians; the founding documents were divinely inspired; America is divinely favored (whence its power and wealth); it must remain pure, otherwise it will be punished.”

It is a false narrative. The Declaration contains a reference to “Nature and Nature’s God” that is more deistic than Christian; the Constitution makes no such references at all. The religious views of the Founders ran the gamut from Calvinism through deism to perhaps even atheism.

Does this mean that the secularists are right—that the United States was founded as a “secular republic”? Not exactly. The Constitution did mandate an institutional separation of church and state. But this did not require an intellectual separation of religion and politics. Theological ideas did influence Revolutionary ideology and popular understandings of American democracy.

The American Civil Religion is also a historical narrative; it goes like this: “America was founded on a civic creed; its founding values are freedom, equality, ‘the general welfare,’ and a ‘more perfect union’; the nation has often fallen short of these ideals, but it continues to pursue them; should it fail, democracy will fail with it.”

Revolutionary era thought drew on two main sources: political philosophy and Protestant theology. The founders knew their Locke but also their Cicero. They were influenced by small-r republicanism but also by what we now call classical liberalism—and not just ideas of the “radical Enlightenment” but the “religious Enlightenment” as well.

The American Civil Religion narrative draws on biblical tropes, including “Exodus,” “covenant,” and “millennium.” The Revolutionaries were fleeing English “slavery,” placing themselves under law, and “beginning the world anew.” They saw no logical contradiction between democracy and Christianity.

This blend of prophetic Christianity and civic republicanism is the germ cell of the American Civil Religion.

Like the American Civil Religion narrative, the White Christian Nationalism narrative also pulls on Scripture. It weaves together three strands of early Protestant political theology:

-

- The idea that the Puritans were a chosen people, the new world their promised land, and the natives the Canaanites;

- The view that the Second Coming would be preceded by a final and imminent battle between the forces of good and evil, between the natural and supernatural;

- the idea that God made the “races” separate and unequal, with Africans “marked” black and condemned to perpetual “servitude.”

These two traditions may be old, but they are far from dead. Trumpism is, among other things, a reactionary and secularized version of White Christian Nationalism. It is reactionary insofar as it sheds the polite euphemisms of “American exceptionalism” that took shape during the Cold War in favor of full-throated language about blood, violence, and race. And it is secularized insofar as it abandons the Christian categories of good and evil and replaces them with those of the German jurist Carl Schmitt, who famously argued that all modern political concepts are secularized theological concepts. For the Christian distinction between good and evil Schmitt substituted an opposition between friend and enemy.

The American Civil Religion is not dead either. In an inaugural address rich in religious references, Joe Biden acknowledged the “ugly reality” of” racism, nativism, fear, and demonization,” but insisted that the nation’s “better angels” would once again prevail. In a more secular vein, Amanda Gorman spoke of “the hill we climb”, the “city on a hill” that is yet to be built.

America is at a crossroads. One path leads forwards towards a multiracial democracy, a nation of nations and a people of peoples. Another leads backwards towards Herrenvolk democracy: a nation of nativists and a people without pigment.

America has been here before: in 1787, 1877, and 1968. Each time it took a step forward, then a step backward. Each time, racial equality was sacrificed on the altar of white power: by slaveowners (1787), so-called “Redeemers” (1877), and proponents of “law and order” (1968).

Which path will it choose this time? The answer is open.

But much will depend on the choices white Christians make in the years to come. Will they join together with their Christian brothers and sisters—and with secular Americans committed to democracy and equality? Or will they once again confuse liberty with power and Christianity with whiteness?

Through the Civil War, the Great Depression, World Wars, and 9/11—through struggle, sacrifice, and setbacks—our better angels have always prevailed. At this decisive moment, we need them to prevail once more.

Philip Gorski is Professor of Sociology and Religious Studies at Yale University. His most recent books are American Covenant (Princeton, 2017) and American Babylon (Routledge, 2020). He is currently completing a book on white Christian Nationalism with Samuel Perry.

Philip Gorski is Professor of Sociology and Religious Studies at Yale University. His most recent books are American Covenant (Princeton, 2017) and American Babylon (Routledge, 2020). He is currently completing a book on white Christian Nationalism with Samuel Perry.