Today, liberals and conservatives square off over religious liberty. Their shared past points to a better end.

This month the Supreme Court’s five most conservative justices united around a significant expansion of religious liberty that the Court’s three most liberal justices opposed. In Tandon v. Newsom the Court’s most conservative justices declared that some of the California state government’s COVID-related restrictions on religious services violated the First Amendment—though the Court’s three liberal justices, along with Chief Justice John Roberts, dissented.

The spectacle of conservative justices advancing constitutional doctrines of religious liberty over the opposition of the Court’s liberals has become the expected norm. This was true in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores (2014), a 5-4 decision in which the Court’s conservative justices ruled that a for-profit enterprise could be exempt from a government health care mandate on religious grounds—an interpretation that, again, the liberal justices unanimously opposed. Later this term the Court will issue a ruling on whether the First Amendment’s free exercise clause gives a Catholic foster care agency that receives government funds the right to refuse placements with same-sex couples on religious grounds. If the recent past is any guide, the conservative justices will vote to grant this right, while the liberal justices will dissent.

But although the pattern of conservative justices supporting expansions of religious liberty against liberal opposition on the Court no longer surprises most Americans, this phenomenon is less than three decades old. From the 1940s through the 1990s, liberal justices were far more likely than the Court’s conservatives to support expansive interpretations of the free exercise clause.

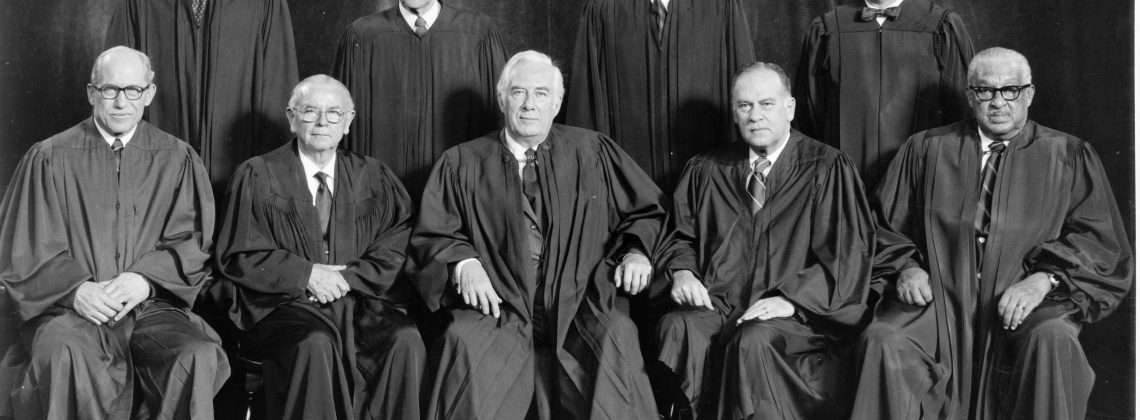

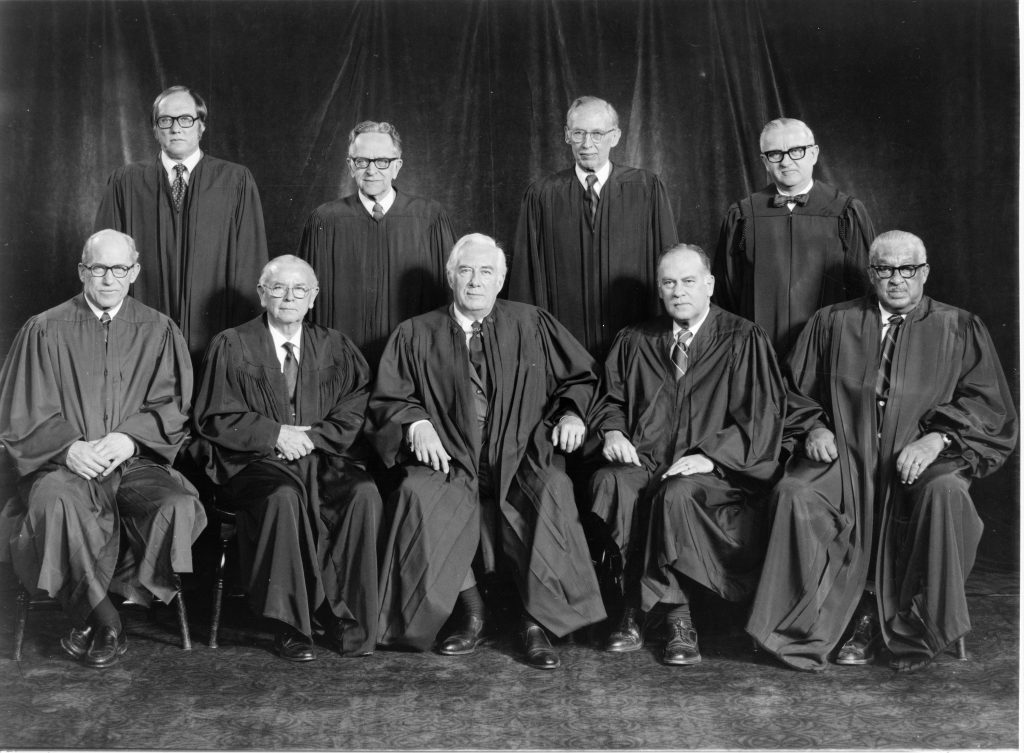

As recently as 1990 the Supreme Court’s most conservative justice at the time, Antonin Scalia, authored an opinion in Employment Division v. Smith restricting religious liberty. Scalia’s majority opinion declared that the First Amendment’s free exercise clause did not protect two members of the Native American Church who were fired from their jobs for violating Oregon’s ban on peyote because of their ritual use of the prohibited substance in religious services. The three dissenters in the case included the Court’s two most liberal justices: William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall. They were joined by Harry Blackmun, best known as the author of Roe v. Wade.

The liberal justices’ defense of religious liberty in 1990 was the culmination of a decades-long postwar phenomenon in which the liberal Warren Court, followed by liberals on the Burger Court, repeatedly voted to expand the free exercise rights of religious minorities who objected to government regulations that violated their conscience. The Court’s liberal majority voted that the state could not compel Jehovah’s Witnesses to salute the flag (1943), deny unemployment benefits to Seventh Day Adventists who lost their jobs because of their refusal to work on the Sabbath (1963), or force Amish children to follow their state’s compulsory school attendance laws (1972). At the time the only dissenters to these Court affirmations of individual liberty were some of the Court’s more conservative justices; the liberals were stalwart supporters of the expansion of free exercise doctrine.

Liberals during the postwar era prized the right of conscience because they were civil libertarians who wanted to protect individuals’ right to dissent. Their views were bolstered by the existentialist philosophy of the 1950s and 1960s, which emphasized the role of the individual in arriving at moral decisions and acting upon them—as Thomas More did, for instance, in A Man for All Seasons (1966), a movie produced at the height of this liberal celebration of conscience.

So strong was the liberal defense of conscience in this era that many liberals believed that it superseded other rights they prized, such as the right of equal access to abortion services. In 1973 Senator Frank Church, a pro-choice Democratic senator known for his civil libertarian views, responded to Roe v. Wade with the Church Amendment, which protected an individual or medical facility receiving state funding from being required to assist in sterilization procedures or abortion services if such actions were contrary to the institution or the individual’s “religious beliefs or moral convictions.” A Democratic, liberal-leaning, mostly pro-choice Senate approved the Church Amendment by a vote of 73 to 16.

Why did this change? Perhaps it is because contemporary progressives no longer define freedom primarily in individual terms but rather in terms of group equality. The liberals of the Warren, Burger, and even early Rehnquist courts were shaped both by the existentialist philosophy of the 1950s and 1960s and by the liberal reaction against the Red Scare of the early postwar era, as well as the Vietnam War that followed it. Protecting an individual’s right to dissent against the majority on the grounds of conscience was what differentiated the United States from a totalitarian country, they believed.

But at the end of the twentieth century, liberals who were shaped by the civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights movements began to see equality as a more fundamental, non-negotiable value than the preceding generation of liberals had. Conscience rights were not sacrosanct if they were used to deny inequality to others, they now believed. When they did defend religious freedom, they focused less on rights of individual conscience than on the rights of religious minorities to be accorded equal treatment with other groups in expressing their religious identity—such as the right of Muslim women to wear a hijab without harassment.

Sometime between the mid-1980s and the late 1990s, conservatives also shifted on religious liberty. Rights of conscience they once had viewed as a potential threat to social order now seemed to be the last defense of a beleaguered conservative Christian minority. In 1972, the Court’s two most conservative justices—Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist—had dissented against the Court’s expansion of religious liberty in Wisconsin v. Yoder, the decision that exempted the Amish from compulsory school attendance laws. Tellingly, by the late 1980s, conservative lawyers were making Wisconsin v. Yoder a cornerstone of their defense of parents’ right to homeschool their children. And in the twenty-first century, conservative Supreme Court justices such as Scalia, the author of the majority opinion restricting religious liberty in Employment Services v. Smith, became strong advocates of religious freedom when dissenting from the liberal majority’s advocacy of equality for gays and lesbians.

So today those who believe that rights of conscience are paramount may feel that conservative justices are their cause’s only champions. But historically, conservatives have not been particularly reliable defenders of the rights of conscience, and it may still be too early to tell whether their newfound interest in the cause is a sign of a genuine reconsideration of the issue, or merely an expression of their longstanding concern to secure the interests of the religious mainstream.

In any case, the cause of religious liberty would be best served if liberal justices as well as conservatives rediscovered the cause that a previous generation of liberals fervently advocated. Is it too late to hope that today’s liberals and progressives can rediscover the right of conscience and the civil libertarian priorities of Frank Church and the Warren court?

Daniel K. Williams is a professor of history at the University of West Georgia and the author of several books on religion and American politics, including God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right and The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship.

Daniel K. Williams is Senior Fellow and Director of Teacher Programs at the Ashbrook Center at Ashland University in Ohio and is the author of several books on religion and American politics, including God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right and The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship.