A late antique bishop forces a rethinking of the Texas abortion law

As the controversial new Texas abortion law went into effect in early September, many historians of religion weighed in, focusing both on the historical attitudes of Christians towards marriage and reproductive rights, and on the complex history of recent America’s attitudes towards politicizing abortion (a topic on which my favorite American historian is the expert). But the subject that I keep mulling over is an ancillary question the law raised, with its $10,000 reward offer for those who successfully prosecute abortion providers: How does one put a price on a human life?

As it happens, the Church has been thinking about this question for a long time, providing both theological and practical responses. Theologically, evangelical Christians agree on the doctrine of redemption: the “buying back” of sinful humanity through Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. But the Texas law shows that in practice, valuing human life is more difficult to quantify. One early bishop, however, provides a thought-provoking answer in a context that has nothing to do with abortion, and yet is directly relevant to the issues at hand.

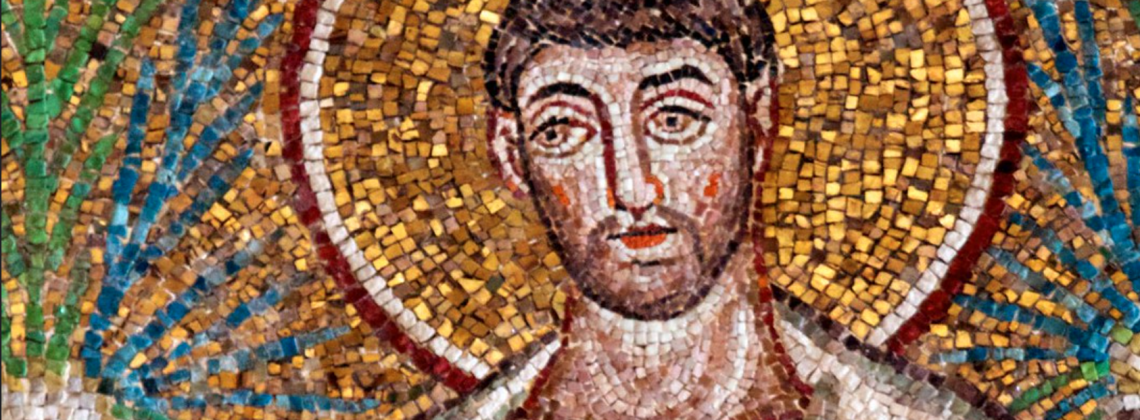

Sometime in the 250s CE, Cyprian, the bishop of Carthage, received a letter from a group of church leaders in Numidia, a region further south and inland from his city, informing him that a group of Christians, both men and women, were kidnapped by “barbarians” and carried off into captivity. The presumed purpose of the capture was the selling of the captives into slavery—a shockingly commonplace experience in the ancient world, and one that became a regular trope in Greek and Roman plays and novels. As for the captors, they were un-Romanized local nomadic groups. In his capacity as the bishop of Carthage, the Church’s largest see in North Africa, Cyprian was the de facto head of the Church in the region. Thus the Numidian pastors’ plea for his help makes sense. Cyprian’s response, while theologically rooted, is also deeply practical in providing a solution to this challenging situation.

Cyprian’s Epistle 62, devoted to this topic, opens with scripturally grounded words of compassion for the suffering of those who have been kidnapped. He is worried, in particular, about the fate of the young women in the group, who were at risk of experiencing rape and even sale into brothels. But after acknowledging the likely horrors the captives were experiencing even as he was writing his letter, Cyprian transitions to the practical solution, which involves cold hard cash. After all, Cyprian realizes, in such a case as this, words are cheap. In asking for his help, the Numidian pastors really needed not just prayer but financial assistance of a kind that their own poorer and smaller rural congregations were unable to provide.

Cyprian does not disappoint: He sends 100,000 sesterces for the buying back of the captives. The money, he notes in a letter, was collected from the contributions of the Carthaginian clergy, laity, and Christians from various congregations who happened to be visiting Carthage at the time. This was no small sum! While it is difficult to convert ancient currency into modern equivalencies, one estimate would place it at a million dollars in today’s currency. That Cyprian was able to raise these funds in short order for this emergency in a time when he and his church were dealing with many other emergencies, including an Ebola pandemic, shows just how critical the Carthaginian Christians considered their responsibility to buy back fellow Christians to be.

Yes, that context—pandemic included—is important. Just how beleaguered were the Christians in the Roman Empire in the 250s CE? The empire was in the middle of what would turn out to be its worst and most prolonged political crisis, with a rapid turnover of emperors and accompanying civil wars. The pandemic was just beginning its vicious twenty-year circulation through the empire, decimating communities, including Carthage, and sowing profound fear in all. Archaeological evidence of the plague provides shocking corroboration of the fear expressed in the writings of contemporary witnesses, including Cyprian, after whom this plague was eventually named. Kyle Harper has argued, in fact, that the pandemic was what ultimately plunged the empire into a deeper crisis. And for the Christians, this was the time of what may have been the first ever systematic empire-wide persecution, when in 251 CE, the Emperor Decius ordered everyone to perform a sacrifice by a specified date.

That Cyprian and the rest of the Carthaginian church raised 100,000 sesterces so quickly in order to redeem their Numidian fellow-believers speaks volumes. They were giving not from abundance but from a place of deep suffering of their own, at a time when no one could be certain when their own life might be taken from them by either the plague or through martyrdom.

I think there is a useful analogy here for us today, as we are living through a pandemic that has already claimed the lives of one in every five-hundred Americans, and resulted in more deaths than births in the state of Alabama last year, a first in the state’s history. What is a human life worth? And how do we show that we value it? At this moment a family in my church is walking through the process of international adoption in order to bring home a child with severe medical needs. Without help and resources, that child’s chances of life are low. Another family we know adopted internationally a sixteen-year-old a few years ago, right before he aged out of eligibility. Life expectancy in his birth country for those who grow up in the orphanage system is in the mid-twenties. By raising tens of thousands of dollars to adopt these children, and by sacrificing their time and energy for years thereafter, families around us offer concrete examples of what it looks like to value life by redeeming it in very literal ways.

How crudely, by comparison, the Texas law, with its monetary reward for informing on abortion providers, comes across, even as the state’s COVID-19 death rates remain among the highest in the US. Why not, instead, direct further funds to support vaccination to save lives, or provide additional resources for expectant mothers from low-income backgrounds, or even support families seeking to adopt or foster? Redeeming the lives of others should take such practical forms, precisely because of the theological assumptions that Christians share. “He who redeemed us on the cross through His blood is now to be redeemed by us through the payment of money,” reminds Cyprian matter-of-factly.

Nadya Williams is Professor of Ancient History at the University of West Georgia.

Nadya Williams is the author of Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan Academic, 2023), Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic: Ancient Christianity and the Recovery of Human Dignity (forthcoming, IVP Academic, 2024), and Christians Reading Pagans (forthcoming, Zondervan Academic, 2025). She is Managing Editor for Current, where she also edits The Arena blog, and Contributing Editor for Providence Magazine and Front Porch Republic.