The president of the Lutheran university in Indiana wants to sell a Georgia O’Keefe painting to pay for the renovation of two dormitories. The story caught the attention of New York Times reporter Kalia Richardson. Here is a taste of her piece:

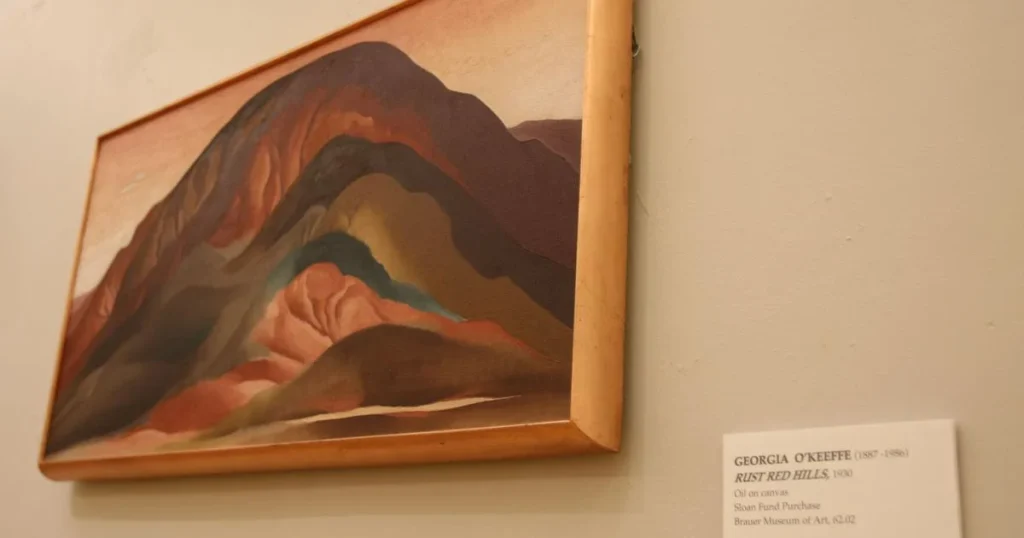

During his decades teaching literature at Valparaiso University, John Ruff looked beyond words, bringing his students to the school’s art museum to help them acquire what he called emotional wisdom. While discussing stories that originated in the Southwest, he would point out Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Rust Red Hills.” When he wanted to draw parallels to 19th-century American literature, Frederic E. Church’s “Mountain Landscape” was right there.

But those paintings may not hang on campus much longer.

Valparaiso, a Lutheran university in northwestern Indiana that is struggling with the declining enrollment seen at many schools, is planning to sell several works from the collection of its Brauer Museum of Art to raise $10 million for the renovation of two freshman dormitories, which it sees as key to securing its future.

The announcement angered many arts organizations and has divided the university: Last week the faculty senate approved a nonbinding resolution that sought to halt the sale and identify alternative ways to fund the renovations.

Richard Brauer, a retired art professor who served as the director of the museum that now bears his name, has told the university’s leadership he wants his name removed if the school goes through with the sale.

“It really does outrage me,” Brauer, 95, said. “I think it’s wrong; the museum profession calls it the worst practice. And I think it’s shameful.”

Valparaiso is among many private colleges and universities looking for ways — such as slashing the advertised tuition price — to combat declining enrollment among a generation of young adults more aware of the burden of student debt. Its enrollment has fallen 39 percent since 2016, to 2,964 students last fall; the law school was shuttered in 2020, and degrees such as secondary education and French have been discontinued.

In response, Valparaiso has developed a five-year strategic plan that includes improving the experience for first-year students. The residence halls date to the 1950s and 1960s, and administrators say they now require significant, expensive renovations. The paintings entered the Brauer’s collection during those same decades, and have since skyrocketed in value. The school saw an opportunity.

Valparaiso’s president, José D. Padilla, said in his announcement to students and faculty that the school was reallocating “resources that are not core or critical to our educational mission and strategic plan.” In a statement to The New York Times, he said that the decision to put the paintings on the market was not made lightly, but that “attracting and retaining students drives the tuition revenue that strengthens our ability to serve our students.”

Read the entire piece here.

Here is a response from 75 Valparaiso University faculty:

Dear Faculty Colleagues,

We, the undersigned, are writing to express our strong disagreement with the recent decision to sell valuable masterworks from the Brauer Museum of Art to pay for resident hall renovation and construction.

We agree with the concerns that our colleague, Gretchen Buggeln, has described in her memo to the faculty senate, dated January 17. We agree with the additional concerns articulated in a subsequent memo, dated February 7, which she and two other colleagues, Sarah Jantzi and Sara Gundersen, sent to the faculty senate. We also agree with the main points that Senior Research Professor John Ruff has raised in his open letter to the university’s president, dated February 6, and that our emeritus colleague Richard Brauer has raised in his email correspondence to the faculty senate, dated January 26, and to President Padilla, dated January 31.

While some of us had recently heard rumors about this decision to sell masterpieces from the Brauer, many of us did not learn of that decision until it was announced via email by President Padilla as a fait accompli on Wednesday, February 8.

We are deeply hurt that such a weighty decision, involving key pedagogical and cultural resources that many of us use in our regular teaching each semester, was made without consultation with the Brauer’s university-authorized Collection Committee, which oversees the museum’s holdings, or with other faculty members, especially with those whose scholarly expertise and research relate directly to the mission of the Brauer Museum and more broadly to that of the university. The lack of shared governance and of transparency about the process by which this decision was made has undermined our trust in the administration.

The sale of the paintings is unethical for the reasons that Dr. Buggeln and others have stated. It will ultimately harm the university, its mission, its integrity, and its image. Given this breach of the trust of benefactors who have enriched our university over many decades, who will ever consider giving a substantial art donation to our university in the future? How can such potential donors trust that the intention of their gift, stipulated at the time of their bequest, will be honored by future Valpo leaders?

According to our mission statement, “Valparaiso University is a community of learning dedicated to excellence and grounded in the Lutheran tradition of scholarship, freedom, and faith.” Those of us who teach and serve here seek to prepare “students to lead and serve in both church and society.” We want our students to be moral leaders in church and society. This decision, however, and the way in which it was made, communicates to our students that “the end justifies the means” and that “original covenants and trusts can be broken if, by doing so, we will reap easy and immediate financial gains.” Certainly, our students will see the problem with how such a sale would violate historic promises and basic ethical principles relating to museum practices.

We are dedicated to excellence, and we recognize this same commitment in the current and previous administrators of the Brauer Museum. If Valparaiso University truly values excellence, then it should provide students (and the wider community) with exemplars of excellent visual art. The aim of such art, in part, is to stir the human imagination (an activity that is so crucial to all academic disciplines), to inspire people to adopt new and hopeful perspectives, to feed souls, and to motivate people for just ends. The liberal arts are not simply a shiny veneer on our professional degrees. The liberal arts are at the heart of our university’s mission, which, in part, is to liberate people from ignorance and prejudice, and to liberate them for leadership and service. The visual arts are crucial to that endeavor. They can help to reveal problematic and laudatory aspects of our world and human beings; they can speak truth to our minds and souls; they can elicit empathy, point to justice, and shed light on realities that only artists can unveil.

This proposed sale of the paintings runs contrary to the university’s Lutheran heritage of supporting the visual arts and the other humanities. Martin Luther’s close friend was the important artist Lucas Cranach Sr., whose woodcuts adorned Luther’s translation of the Bible. Luther’s theology has influenced many other artists from Albrecht Dürer to Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, and Sadao Watanabe, and they have each brought “word and image” into a creative dialectic for the sake of summoning faith and exhorting people to loving service. Subsequent Lutheran theologians, notably Paul Tillich, have also stressed the revelatory power of excellent visual art, to reveal the sacred, and to shed light on human beings and the rest of God’s creation. Is it any wonder that O. P. Kretzmann promised to fulfill Percy Sloan’s wish to operate the Sloan Collection as “actively as is the college library” for the benefit of students and the community?[2] In the same vein, President Huegli was right to stress the importance of the arts, and he did everything he could to ensure that Valpo students would learn about world cultures. What would our late colleague Prof. Gus Sponberg, who cared so much about the centrality of the arts for human flourishing, say if he were alive today? We can only imagine how he and so many other former Valpo professors, especially those whose passion was sparked by the arts and the humanities, would lament this recent decision.

We will end this letter by citing the advice of the late Richard R. Caemmerer Jr., former professor of art at Valpo (and one of the great American-Lutheran artists of the twentieth century). Prof. Caemmerer was often consulted about liturgical art in Lutheran congregations and those of other Christian church groups, and he occasionally encountered individuals who said, “Why are we spending so much money on art when we could be directing our money to [fill in the blank]?” Prof. Caemmerer’s response is our counsel to President Padilla: “Find the money elsewhere so that you can support both the artwork and [fill in the blank].” Our art collection and resident halls are both important. Do not play one against the other. A third way must be found to maintain both things.

Please, do everything you can to reverse this imprudent action. We can find another way to avoid selling our most valued art treasures in order to improve resident halls. (What will Valpo’s leaders do in twenty years when these same buildings need renovation again? Sell more masterpieces? Who will buy them? What will happen to Valpo’s historic treasures?) This action is not just the sale of a few paintings. It is the sale of part of our institutional identity, part of our institutional soul. It undermines our integrity as a liberal arts university that is grounded in the Lutheran tradition.

Many of the students who are currently living in our resident halls do not want the university to sell these precious masterpieces merely to make their living spaces “more attractive” to prospective students. As a Valpo first-year student told one of us on Friday, “I didn’t come to Valpo to live in a fancy dorm. I came here to get a quality, affordable education. I live in Brandt Hall, which probably could use some updating, but I don’t want such improvements to be at the expense of these important pieces of art.”

Finally, we do not intend this letter to be a public rebuke of President Padilla. We want to support his efforts to lead our university. We especially commend him for his Christian witness to students and others (for example, when he talks about “Homeless Jesus” with first-year students and when he speaks “heart-to-heart” with graduates, as he did at the December commencement). We simply disagree with the proposed sale of these paintings. We hope that this decision will be reversed, and we are ready to think creatively about how to fund the proposed resident hall renovations and construction. We should be able to safeguard our art collection and do this other thing as well.

As some of you know, I taught at Valparaiso from 2000-2002 as part of the Lilly Fellows Program in Arts and Humanities.

I don’t know what I’d do if I was on the faculty at Valpo. The administration should have convinced–or at least TRIED to convince–the collections committee to sell the paintings, for sure. Should they sell them to renovate 1st-year dorms? Since the invention of universities, students have lived in spartan–monastic?–circumstances in order to have access to the life of the mind. MY ideal of the university says it is better to live in barracks and have access to great art (and a French major) than to live in modern comfort for…let’s just say, the emerging alternative.

But, 10 million dollars is a lot of money–even for Valparaiso these days–and “get it from someplace else” is easy for people like me to stay. If students won’t come without fixing the first-year experience, then what good are the paintings? You don’t destroy the village in order to save it–absolutely. It wouldn’t destroy the mission of my family or my church if we needed to unload valuable art to keep going. The university? in this case? Tough to say.

This is the dilemma of liberal education–and institutions committed to it–in the time and place we live.

John, I did not know you were a Lilly Fellow back when. I was a representative to the Network lately, and have respect and appreciation for the program and my friends involved going way back…