A haunted and haunting journey through uncanny (big) valley

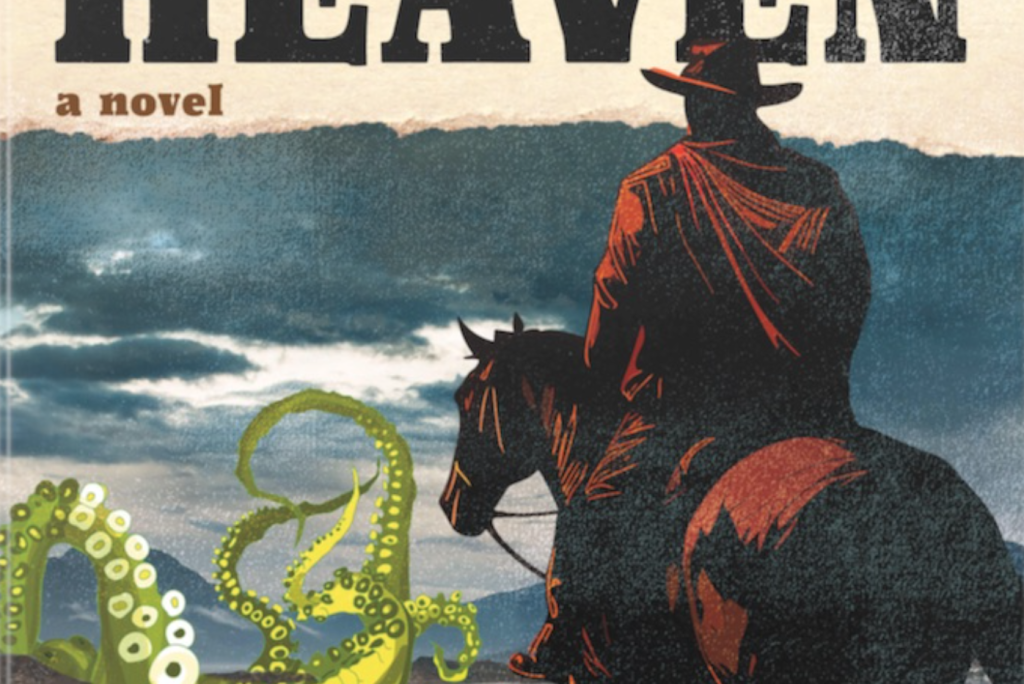

The Country Under Heaven by Frederick S. Durbin. Melville House, 2025. 321 pp., $20.99

Two classic literary and film genres are the Western and horror. The typical Western motif follows a hero and a villain, each of them living outside of town and in comfort with violence. The villain uses his proficiency to terrorize the townsfolk while the hero comes to their aid. At the end of the story, the hero vanquishes the villain and rides off into the proverbial sunset.

Horror boasts greater variety. Usually these stories begin with normal people going about daily life. At some point, a barrier breaks between the natural world and the supernatural. At first denizens of the natural world refuse to acknowledge the supernatural. When their scientific means of explaining the strange occurrences fail, though, they are eventually forced to deal with the reality of the supernatural. They are aided by some kind of spiritual leader, like Van Helsing in Dracula, who helps to vanquish the otherworldly evil.

What if we combined these two genres? That is what novelist Frederic S. Durbin does in his latest, The Country Under Heaven. The book advertises itself as a combination of Louis L’Amour and H.P. Lovecraft. This seems fair enough. Durbin is to be commended for a bold, original take on two different genres. Does he succeed?

The novel is the tale of Ovid Vesper, a Civil War veteran haunted—literally—by his wartime memories. The tale begins in 1880 in Missouri, with Ovid visiting an old war buddy and his wife, both suffering from their daughter’s unsolved murder. One day a traveling show comes to town. Doctor Bellerophon Cinch promises to bring a “message from beyond.” He does just that, channeling the murdered young woman, who reveals her slayer’s identity. A chase and a shootout ensue, ending poorly for the murderer.

This is the first in a series of tales as Ovid wanders around the American West for the next decade. The story is told in episodic fashion. The novel, not unlike Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, is a series of short stories loosely following a larger arc, all featuring Ovid as the main character.

Ovid is pursued by a spirit he calls the Craither (i.e., creature). In each story the Craither appears, clearly signifying Ovid’s unreconciled grief and horror from the war. The Craither seems related to a power Ovid has: the ability to see the future or into other worlds.

In each chapter, Ovid arrives in a new place, meets some nice people, and begins to settle down. We get hints, however, of some portentous, foreboding circumstance. Next, Ovid is forced to use his powers of second sight to help solve the problem, usually at some cost to those whom he has befriended. Finally, in typical Western fashion, he leaves to pursue his fortune elsewhere.

For someone haunted by war memories, Ovid seems remarkably unaffected by his recurring bouts with the paranormal. Whether encountering aliens from another world or dragons, he has the most amazing encounters and then seemingly forgets them by the next story. Ovid doesn’t really grow or change from his experiences. He witnesses considerable death in this novel, sometimes as a result of his own gunplay, but it doesn’t seem to alter his behavior.

In this sense, Ovid resembles Indiana Jones, or Scully from the television show The X-Files, who after each encounter with the spectral seems to forget and must learn again in the next movie/episode. While Ovid doesn’t have to relearn his respect for the supernatural, he does appear remarkably insouciant regarding each ensuing unnatural occurrence. And his fellow Westerners, surely not as accustomed to the paranormal as Ovid, take the unusual rather nonchalantly.

Consider this: If you had as many encounters with horrifying beasts and otherworldly monsters as Ovid Vesper, you might think twice about wandering the Western plains. One might either become a hermit to spare people the horrors that seem to follow, or perhaps move to a big city where presumably ancient, hidden evils have already been rooted out by the sheer number of people. If you are literally being followed by a ghost, perhaps you shouldn’t bring that ghost to your friend’s house.

Durbin fails to create the verisimilitude and sense of foreboding that typically makes horror work as a genre. One thinks of Agatha Christie’s Endless Night (not a detective novel). Christie instills in her story a sense of tension and apprehension—a sense that something is just not right. In short, the novel is genuinely creepy.

There is nothing creepy about The Country Under Heaven, however. The ready acceptance of the unusual by most characters detracts from the tension that is at the heart of true horror stories. If you saw a dragon erupt from the Kansas plains, your next reaction probably wouldn’t be “Well, gotta get these cattle to Dodge City.” The stories do not reach that ambiance of eerie foreboding that makes horror stories such naughty fun.

Durbin would have been better served by doling out his supernatural elements more judiciously rather than wantonly. He could have kept the gunplay to a minimum rather than making it commonplace. The character of Bellerophon Cinch presents unrealized possibilities. He appears in one story and is referenced in another. He seems a notorious character, a master of dark arts, lacking in scruples. One wants to learn more about him. But he is introduced early, referenced once more, and then disappears.

While The Country Under Heaven is a bold effort, as a Western it lacks adventure and a consistent villain, and as a horror story it stops short of the intriguingly uncanny that represents that genre at its best. Still, those who truly like monster stories—and good stories in general—will enjoy this novel.

Jon D. Schaff is Professor of Political Science at Northern State University in Aberdeen, South Dakota. He’s the author of Abraham Lincoln’s Statesmanship and the Limits of Liberal Democracy and co-author of Age of Anxiety: Meaning, Identity, and Politics in 21st Century Film and Literature.