Even Lamar can’t defeat the Super Bowl

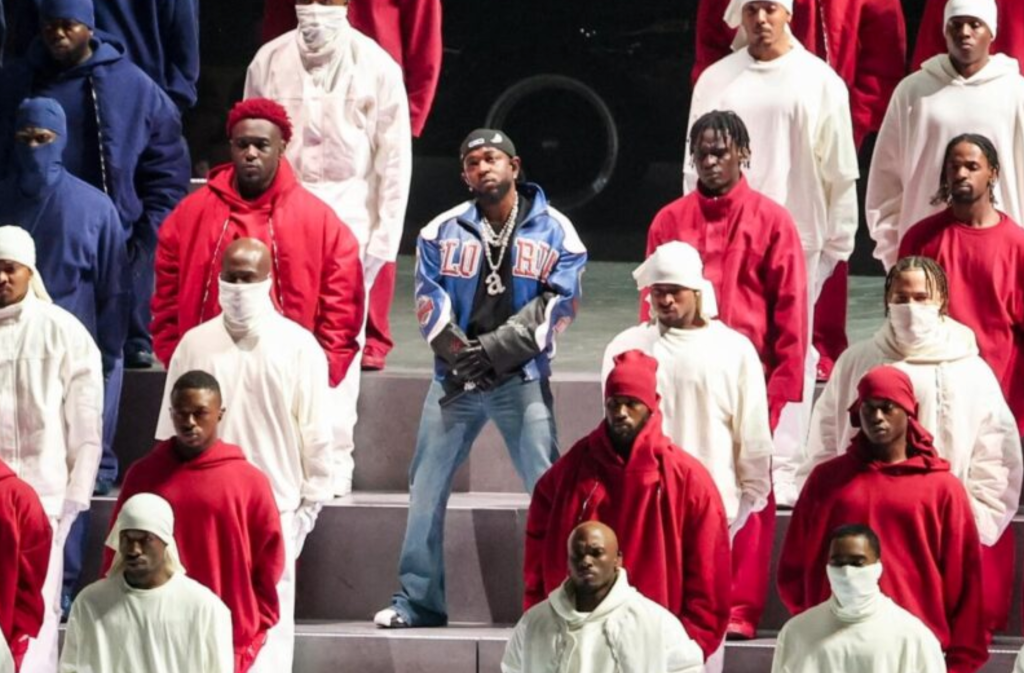

This week my social media feed has been filled with explanations of the symbols, imagery, and messaging of Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show. The comments sections have been a predictable mess. Behold the most recent skirmish in the culture wars.

There are two, largely disconnected, reactions.

Defenders of the halftime show have emphasized Lamar’s ability to speak to the alienation many feel right now: of the head-spinning events of our political moment, of the experience of Blacks and other minorities in America, and of the capacity of rap to say something substantive about our culture.

Critics focus on the technical aspects (e.g., it was hard to hear the lyrics) or the lack of visual appeal. To critics, the performance just wasn’t that entertaining and its overall point unclear; the lyrics were obscene; Lamar did not perform his biggest hits.

In a rare moment in the culture wars, I find both sides offering strong points. I agree with one side that the halftime show was a display of social criticism and artistry. At the same time, it’s also true that this criticism, delivered in the middle of the largest commercial event of the year, failed to conform to expectations—and thus blunted its own force. Whatever message the show intended to send was defeated before the Super Bowl started. Such is the nature of the Super Bowl.

This mess confirms Marshall McLuhan’s dictum that the medium is the message. This aphorism itself is famous, but McLuhan’s explanation of it is just as important: “This is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium—that is, of any extension of ourselves—result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.” In laymen’s terms, the “consequences” (in the case of the halftime show, its significance) are dictated largely by the technology (television) and by the framing of the substance within that technology (a halftime show of the Super Bowl).

On the technology of television, we might do worse than resort to a protégé of McLuhan’s, Neil Postman, who had very little good to say about television in Amusing Ourselves to Death. I am most familiar with Postman’s critique of televised religion, which I think makes a good proxy for art or social criticism. Religion, like social criticism, is about more than entertainment. Religion, like social criticism, is an uneasy fit with television, a medium whose most natural outputs are commercials, live shows, and drama series. In Postman’s words:

On television, religion, like everything else, is presented, quite simply and without apology, as an entertainment. Everything that makes religion an historic, profound and sacred human activity is stripped away; there is no ritual, no dogma, no tradition, no theology, and above all, no sense of spiritual transcendence. On these shows, the preacher is tops. God comes out as second banana.

Substitute “preacher” with “social critic” or “artist,” and “God” with “social criticism” or “artistic message,” and we see how any attempt to intentionally convey meaning in television beyond the medium’s conscribed strengths is, to say the very least, facing an uphill battle.

Yet it is not just that Lamar performed a complex and layered social critique—what Postman calls an “authentic object of culture.” It is that he tried to do so at the halftime of the Super Bowl. Why he would try is obvious. If the ratings are to be believed, this was the most viewed halftime show in Super Bowl history, with more than 133 million people watching. What better platform upon which to speak one’s truth?

On the other hand, the format of the halftime show does not allow for anything but the most commercialized, (de)contextualized forms of sensation. As Postman observed (and he wasn’t even contemplating the special demands of a halftime show): “Television is at its most trivial and, therefore, most dangerous when its aspirations are high, when it presents itself as a carrier of important cultural conversations.” The same problem plagues the “He Gets Us” ads and Jeep commercials that offer musings on the nature of freedom. In effect, every year the Super Bowl halftime show is a genre that “presents itself as a carrier of important cultural conversations.”

Consider the framing of this year’s rendition:

The segment begins with an announcer declaring, “The National Football League welcomes you to the Apple Music Super Bowl Halftime Show.” A portal shaped like the Apple icon transports the viewer to the football field, where the first image is the four PlayStation video game controller symbols (surely this imagery is coincident with the Apple-Sony partnership on VR and video games signed in December 2024). Thirteen minutes later, after Lamar’s final “Turn this TV off,” the announcer’s voice returns, reminding viewers that the performance was brought to them by the National Football League and Apple Music. Within less than three seconds, the announcer notes that a six-month plan of Apple Music is only $2.99/month.

As Americans—as TV watchers—we are largely oblivious, because of its ubiquity, to the drastic context shifts the medium feeds us moment by moment. Beer commercials follow the most dramatic and serious scenes of television shows. The local news program shifts from a heartbreaking crime story to lighthearted banter. But our obliviousness doesn’t mean we are protected from the associated harm.

There’s a reason movies don’t stop for commercial breaks in theaters. There’s a reason most Americans find it cringe-inducing for a speaker to self-promote during a commencement speech. There’s a reason a baby shower is not the time to cajole a group into a discussion of the most recent humanitarian crisis, even if that crisis is unfolding in real time.

And so, to put it plainly, there’s a reason trying to say anything of substance during the middle of the Super Bowl is destined to be misunderstood, dismissed, discarded. That reason is that the medium of television is already stacked against this purpose, and the Super Bowl halftime show raises that stack to a towering mountain.

This is especially true from a Christian perspective—which I say as one who enjoys the Super Bowl. In the Book of Revelation, John the Seer has a disturbing and extended vision of Babylon at the height of its worldly power. It is the center of commerce and luxury, the epitome of culture and class. It is riven with sexual immorality, self-obsession, violence and greatness. It connects all the peoples of the earth for its own benefit. I wonder if, in whatever mind-spinning images John experienced, an impression of a modern Super Bowl flashed across his eyes.

The Super Bowl, for all its glamor, entertainment, and fun, is riven with luxury, exclusivism, and (most recently) gambling. February 9, 2025, is now the day in history that the most people on the planet gambled on a single sporting event. More than sixty-eight million American adults (nearly one quarter of all) gambled away more than $23 billion. Across the country more than half-a-billion dollars’ worth of alcohol was consumed.

But there is one final danger of which the defenders of Lamar’s halftime show must beware. By elevating his performance as a model of social criticism, we risk altering our collective expectations of social criticism itself. As Postman concluded about religion and television, “The danger is not that religion has become the content of television shows but that television shows may become the content of religion.” Replace “religion” with “insightful cultural criticism from our country’s leading artists” and the point stands yet stronger.

The Super Bowl halftime show produced exactly what it was intended to produce. We are the poorer for it (though the NFL is the richer) if this extravagant annual commercial is not understood as simply that and nothing more.

Daniel G. Hummel is an American historian and Director of the Lumen Center on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His work can be found at www.danielghummel.com