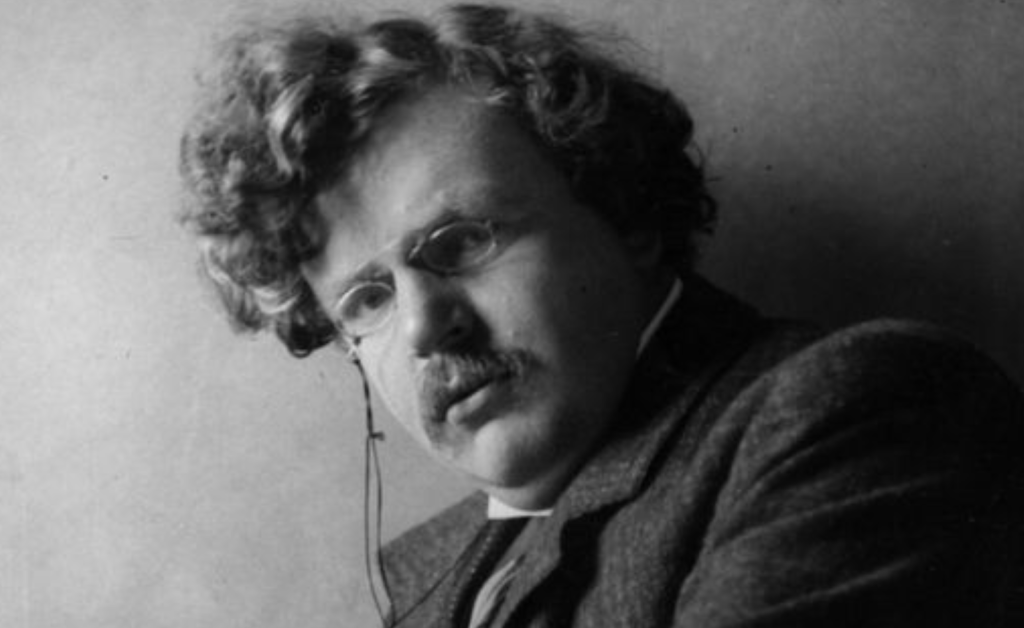

Chesterton’s ‘The Everlasting Man’ is one hundred years young

Oscar Wilde was a naturally spiritual person, whereas G. K. Chesterton was a naturally worldly one. Wilde was drawn to the ethereal, while Chesterton was drawn to the earthy. Wilde’s idea of a night out would have been to see a lighter-than-life production of Swan Lake, while Chesterton’s would have been to go down to The Swan to have roast beef, potatoes, and a pint of ale. Yet Wilde and Chesterton had one thing in common: a mischievous delight in inverting a truism in order to startle people into seeing a truth.

Chesterton’s masterpiece, The Everlasting Man (1925), turns one hundred this year. It still smirks with paradoxical inversions:

“The statement that the meek shall inherit the earth is very far from being a meek statement.”

“It was none the less like the modern ideas because it was as old as Asia; most modern ideas are.”

“Superstition recurs in all ages, and especially in rationalistic ages.”

Dale Ahlquist has produced a new edition, which he expanded to an even more substantial girth by including his own introduction, notes, and commentary. Ahlquist, however, refuses to play the straight man. Like Bing Crosby with Bob Hope, he is ever scheming to steal some laughs as he boisterously accompanies Chesterton on The Road to Rome. For instance, see Ahlquist’s note explaining Chesterton’s reference to Louis de Rougemont (a name that turned out to be an alias used by the fabulist Henry Grin): “His greatest actual accomplishment was meeting G. K. Chesterton and being mentioned in The Everlasting Man.”

Chesterton wrote The Everlasting Man as a Christian retort to H. G. Wells’ The Outline of History (1920). Chesterton praises Wells’ bestselling book, then drily observes: “The one thing that seems to me quite wrong about it is the outline.”

The Everlasting Man seeks to tell the story of humanity in a way that most emphasizes what most matters. It has two parts, “On the Creature Called Man,” and “On the Man Called Christ.” The first part underlines how different in kind (rather than just degree) people are from all other creatures. Repeatedly Chesterton pushes back against the fashion of seeing human beings as just another animal species: “It is customary to insist that man resembles the other creatures. Yes: and that very resemblance he alone can see. The fish does not trace the fish-bone pattern in the fowls of the air.”

Chesterton is not impressed with those who try to span this vast gulf by imagining that there must have been some now undetectable bridge, same fragment of the ruin of which we can pretend we are just on the verge of finding—this “talk of searching for the habits and habitat of the Missing Link; as if one were to talk of being on friendly terms with the gap in a narrative or the hole in an argument, of taking a walk with a non-sequitur or dining with an undistributed middle.”

The so-called cavemen are often depicted in our culture as almost the same as the lower animals, just stupidly grunting and dragging women about by their hair. Yet that depiction is simply made up. What we actually know for sure about the cavemen is that some of them were artists. This is indisputable because some of their paintings have survived. Yet this fact reveals that they really were human beings and therefore radically different from all other creatures: “It sounds like a truism to say that the most primitive man drew a picture of a monkey” and “it sounds like a joke to say that the most intelligent monkey drew a picture of a man.” Chesterton teases readers with his speculation that perhaps the prehistoric cave dwelling with the paintings of animals was a daycare center decorated with a mural for entertaining the children. I remember once touring a museum. The guide remarked that for a long time the objects in a particular case had been misidentified as everyone thought of these people as “primitive savages,” and therefore could only imagine them possessing weapons or tools. It became obvious, however, once this stereotype was set aside, that these objects were children’s toys.

Part Two is on the Christ, the Everlasting Man of the book’s title. As it happened, for my sins, while I was reading Chesterton’s masterpiece I was also reading: Letters from Julia: Light from the Borderland: A series of messages as to the life beyond the grave received by automatic writing from one who has gone before (1899). In it, our loquacious, reputedly deceased source tries hard to reassure Christian readers by saying orthodox things, especially emphasizing salvation through Jesus Christ. Nevertheless, her theme is what life is like after death, and these assertions are casually—indeed, apparently naively—in marked contrast to Christian teaching. Julia insists that to be embodied is to be encumbered. The joy of the afterlife, according to this spirit guide, is the freedom that comes with not having a body. She is apparently entirely ignorant of the very existence of the doctrine of the resurrection of the flesh, let alone of its profound import.

Chesterton wants to make the familiar strange; he wants bored, determinedly modern people who were raised as Christians to arrive back where they started and know the place for the first time.

G. K. Chesterton was a man of this world. His God is the God of earth and altar. The gospel story starts in another cave, in Bethlehem, the place where God himself became incarnate in Jesus Christ. This is a startling revelation: “It is no more inevitable to connect God with an infant than to connect gravitation with a kitten.” You can reject this story, but don’t pretend it is just the kind of thing that all religions and cultures have always said. You must see the claim for what it is, in all its utter strangeness. And you might show some curiosity when you also observe that age after age has announced that the Christian faith has now been discredited, yet it somehow always rises again. Truly did Christ declare, “Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away.”

Chesterton was an earthy man because he was right with God and man. He believed in—and proclaimed—a gospel in which the Eternal One decided to take on flesh, to become truly human, to become earthy, to dwell in a body formed from the dust of the ground.

Timothy Larsen teaches at Wheaton College and is an Honorary Fellow at Edinburgh University. He is the author of Twelve Classic Christmas Stories: A Feast of Yuletide Times, John Stuart Mill: A Secular Life, and the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Christmas.

GK exemplifies how Christian scholarship can be fun.