The demands of capital savaged hope

An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South by Robert K. D. Colby. Oxford University press, 2024. 360 pp., $35.00

In May 1861, Sheppard Mallory, James Townsend, and Frank Baker sought refuge from slavery at Fort Monroe, Virginia. They were not the first enslaved people to seek protection from U.S. soldiers, but the response of Gen. Benjamin Butler, the Fort’s commanding officer, anticipated changes in how the United States pursued the war. Defining the three men as “contrabands of war,” Butler refused to return them to their owner, who had leased their labor to the Confederate army, and whose decision to sell them further south may have triggered the flight to Fort Monroe. Congress soon legalized Butler’s decision in the first of two Confiscation Acts. From the earliest months of the war, Lincoln’s war to preserve the union merged with enslaved people’s struggle for freedom. It became an often brittle alliance to save the nation by destroying slavery.

Robert K. D. Colby does not begin An Unholy Traffic with Fort Monroe. Still, this oft-told scene of the first “contrabands” reflects the forces at work in this excellent history of the slave trade, the lived experience of the Civil War, and the wartime destruction of slavery. Colby demonstrates that slave trading persisted during the Civil War because of—not despite—military, social, and economic upheaval. The uneven presence of moving armies both disrupted and reestablished slave trading networks. The threat of being sold might keep an enslaved person’s freedom dreams in check, or it could prompt a break for freedom to places like Fort Monroe. Robert Lumpkin’s infamous slave jail in Richmond, Virginia, operated right up to the evacuation of the Confederate capital. The slave trade even survived Appomattox.

Measured by price indexes, the slave trade reached its apex in the decade before the Civil War. Spurred on by the transportation revolution and the settlement of the Cotton Kingdom, prices for enslaved people outpaced the cotton market so that downturns in cotton prices no longer predicted downturns in the prices of people by the 1850s. This decoupling of cotton and slavery continued during the Civil War. Secession, King Cotton Diplomacy, and—eventually—an effective U.S. blockade of southern ports wrecked the cotton economy. These events disrupted the slave trade, but the internal buying and selling of humans became attached to the rise and fall of the Confederate state. “As nation struggled against nation, brother against brother, enslaved against enslaver, the commerce in slaves became both a sinew of war and an indicator of its course,” Colby notes. “It was a means of fighting the conflict, equipping its armies, and waging the home front battles the enslaved almost immediately inaugurated.”

The persistence of the slave trade reveals more than the emotional ups and downs of military and civilian morale. Trading continued in areas of Confederate control during setbacks as well as advances. Intergenerational wisdom among white Southerners held that land and slaves made the best investments. Even causal glances at eighteenth and nineteenth-century probate records or the 1860 U.S. Census reveal this pattern. Southern slaveholders’ wealth was tied up in land and, especially, people. “The high prices they willingly paid for human property,” Colby writes, “indicate that Rebels believed this would not change.”

Bleak wartime economic conditions encouraged white Southerners to double down on the slave trade. Inflation during the first three years of war rose at a rate of ten percent per month. Some goods rose 700% by the winter of 1862-1863. Colby indicates that markets for purchasing or renting enslaved labor prospered early in the war but not at the same levels. Inflation encouraged enslavers to turn paper currency into property: “The Confederacy lacked sufficient specie to make hard currency a viable investment option, and while some preferred other nodes of the slave economy (land or cotton), many considered the enslaved the most promising investment.” Widespread inflation also gave slaveholding debtors an opportunity to pay off their creditors. In war as in peace, wealthy white southerners balanced their investments during uncertain economic times by breaking up enslaved families and communities. The buying of enslaved people also reflected widespread confidence that, one way or another, the Confederate state would survive the war.

The faith in the continuation of slavery, right up to the end of the war, dashes neat timelines about an unstoppable march toward freedom. Modern Civil War historians, including Colby, situate African Americans as central participants in the downfall of slavery. The men, women, and children who fled to U.S. lines proved much more than so-called contrabands. Individual stories of men, women, and children made it difficult for U.S. soldiers and statesmen to hide behind abstract property rights. Collective action from manual labor to serving in the United States Colored Troops led African Americans to initiate a conversation about citizenship rights. And yet eighty to eighty-five percent of those enslaved at the beginning of the war were still enslaved at the end of it. Colby breaks from the triumphant narrative by counterbalancing the slave trade against self-emancipation.

The wartime slave trade serves as a reminder that the tools of resistance were also the weapons of oppression. If enslaved men and women feigned illness as a means of daily resistance, slaveowners might sell that person while endeavoring to conceal any illness. Forging loving partnerships within enslaved communities and bearing children, perhaps the greatest resistance to the dehumanizing forces of enslavement, created emotional bonds enslavers might one day manipulate with threats or break apart for myriad reasons. Even mobility worked with and against enslaved people when slaveowners sold off those engaged in visible resistance.

If the slave trade served as an “economic safety valve” for Confederate slaveowners, it also gave them a powerful weapon against the freedom dreams of enslaved people. “Slave commerce could neither hold emancipation at bay nor entirely offset enslaved people’s exodus,” Colby writes. “But at an individual level, it permitted slaveholders to counter the revolution unleashed by the war and lent them a potent weapon to wield gains their bondspeople’s aspirations.” As the war dragged on, slaveholding men and women turned to the marketplace for retribution over even small infractions. Slaveholders doubled down on cruelty in the final months of their power to break up families. Indeed, these final years marked the greatest fracturing of enslaved families.

The greatest challenge of recovering the history of the wartime slave trade is that most surviving records come from the perspective of enslavers. Testimony from enslaved people, with several important exceptions, is almost always filtered for and through the eyes and ears of white Americans. Yet Colby is a meticulous textual historian who spends relatively little space on speculation. He closes this gap with a concluding chapter on the ways freed people sought to restore the bonds of family broken by the wartime slave trade. For people like the brothers Richard and John Johnson, the reunion took more than four decades. No reunion ever took place between Richard Johnson and his mother, Upshur, who filed a pension application thinking her son was long dead and died herself before the Johnson brothers exchanged letters in 1906.

A second way Colby brings focus to African American experiences is by introducing and concluding the book at the same place—Robert Lumpkin’s slave jail, or what enslaved people called the “Devil’s Half Acre.” The author’s opening vignette narrates how Lumpkin took fifty men in chains from his jail to the railroad depot on April 2, 1865. The slave trader failed to convince railroad officials to aid him in fleeing the capital to a place still safe to sell human property. The concluding chapter returns to Lumpkin’s jail—and a debate between the self-emancipated Harriet Jacobs and a former slave trader. The public exchange—a Black woman rejecting a slave trader’s claims of benevolence—demonstrates what had changed in only a month, and it foreshadows the long struggle to come over the memory of slavery. Colby’s brief epilogue summarizes the history of Devil’s Half Acre as symbolic of the broader forgetting and remembering of the slave trade.

Today Devil’s Half Acre, nearly obliterated by I-95, has become a center of Richmond’s recent self-reckoning with the legacies of war and slavery. Far from forgotten, this reimagined space serves as a model for how other sites of the wartime slave trade might tell their stories. If this unfolds, An Unholy Traffic will be an essential guide for thinking about the big picture of slave trading, war, and the experience of slavery’s downfall.

Evan Kutzler is a public historian and an associate professor of history at Western Michigan University. He is the author or editor of several books, including Living by Inches: The Smells, Sounds, Tastes, and Feeling of Captivity in Civil War Prisons.

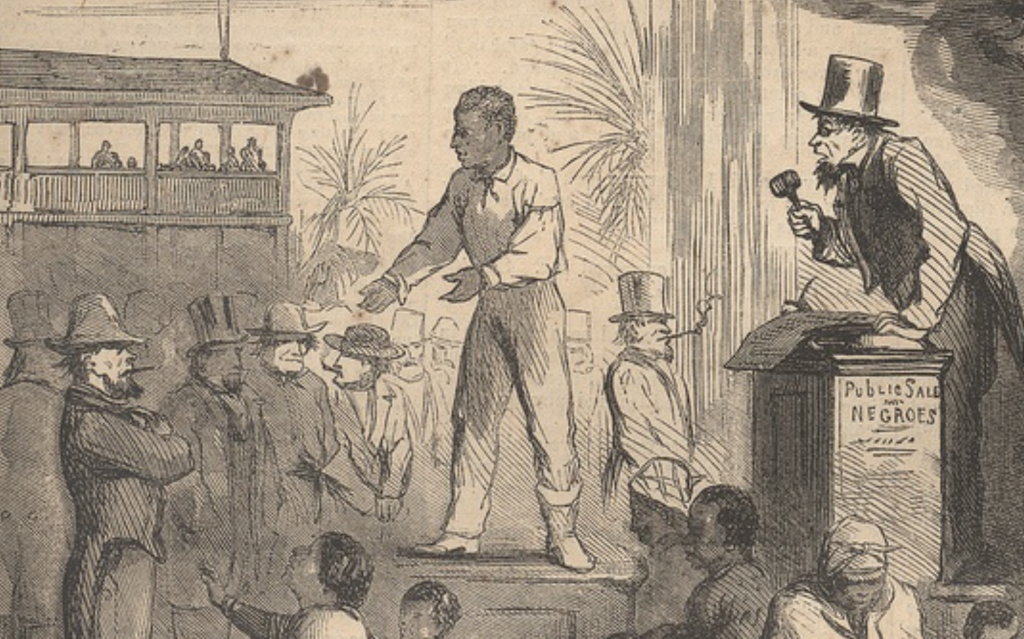

Image: Thomas Nast, c1865