Over at Jacobin, Melissa Naschek interviews New York University sociologist Vivek Chibber about identity politics and the Democratic Party.

Here is a taste:

Melissa Naschek: The Democratic Party has become almost synonymous with identity politics. How did the Democrats get to this point?

Vivek Chibber: Let me start by agreeing that Kamala Harris didn’t run on identity politics. So why is her loss being attributed to identity politics? Is it untrue?

She didn’t run on identity. In fact, compared to Hillary Clinton, Harris steered clear as much as she could from identifying herself as a woman and as a person of color and —

Melissa Naschek: Right. Trump even tried to race-bait her.

Vivek Chibber: Yes, and she didn’t take the bait. So that observation is true, that she didn’t run on it.

Nevertheless, it is also true that identity politics played a big role — although not a deciding role — in her defeat. The deciding role was economic issues. Largely, it didn’t really matter that she didn’t run on identitarian terms. She was going to lose anyway because of economic issues.

But make no mistake: even though the association with identity didn’t cause her defeat, it was a big factor. And to ignore that would be a big mistake.

So how did she and her party become so closely identified with identity politics, and what role did it play? First of all, even though she steered clear of it, the party has been propagating it in a very aggressive way over the past six or eight years. So dropping it at the eleventh hour didn’t fool anyone. And that’s why Trump’s ads were so effective in attacking her as somebody pushing identity politics down people’s throats — the Democrats had been doing it for eight years already.

As with so many things in our political moment, it goes back to the initial Bernie Sanders campaign. The Democratic Party’s answer to Bernie Sanders’s propagation of economic justice and economic issues was to smear him as somebody who ignored the plight of what they love to call — their new term — “marginalized groups,” which is people of color, women, trans people, all matters dealing with sexuality. This was their counter to the Sanders campaign, and they’ve used it assiduously now for eight years.

So, if in the last two months they decided to pull away from it, who do they think they’re fooling? Literally nobody. And that’s why the turn away from identity politics failed, because it just seemed so ham-handed and insincere. Nobody bought it.

As for the deeper question about the roots of identity politics in the Democratic Party, I think it’s a historical legacy in two ways. The first is an obvious one. Coming out of the 1960s, when the so-called new social movements emerged, the Democrats were the party that upheld and supported those demands. Even when they were demands for the masses, not just for elites, this party supported them — unlike the Republicans, who were the party that resisted the feminist movement and the Civil Rights Movement. So that’s one historical legacy.

The second legacy is slightly more subtle, which is that, coming out of the New Deal era, the most important electoral base of the Democrats was the working class, and this class was overwhelmingly located in urban centers, large cities, because that’s where the factories were. After the ’80s, the geographical location of that electoral base didn’t change, it was still cities, but the cities changed. Whereas cities used to be the place where blue-collar workers and unions were based, by the early 2000s, cities became reorganized around new sectors — finance, real estate, insurance, services, more high-end income groups.

The Democrats were still relying on the cities for their votes, but because the cities’ demography had shifted, it had a profound effect on the electoral dynamics. Affluent groups became the base of the party, and race and gender became reconceptualized around the experiences and the demands of those affluent groups.

So the Democrats were depending on a much more affluent voting base than they had in the past. At the same time, organized pressure from working-class minorities and women was declining because of the defeat of the union movement, and the main organizations taking their place in the Democratic Party were the nonprofits and business.

Take the issue of race. In the high tide of liberalism, the black working class had a voice inside the Democratic Party through the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and the trade unions, and they brought anti-racism into the party through the prism of the needs of black workers. When the unions are dismantled and trade unionism in general goes into decline, who is voicing the concerns of blacks? It’s going to be the more affluent blacks and black political officials that have come up through the post–civil rights era.

And those politicos, by the 2000s, are spread all across the country. There’s a huge rise in the number of black elected officials, mayors, congressmen, etc. And they now no longer have any reason to cater to working-class blacks because workers are politically disorganized. The political officials end up captured by the same corporate forces as the white politicians — but they get to have the corner on race talk.

By the 2000s, race talk and gender talk has been transformed from catering to the needs of working women and working-class blacks and Latinos to the more affluent groups who are the electoral base of the Democratic Party in the cities. And even more so by the politicos who now have increased in number tremendously, aided by the NGOs that do a lot of the spadework and consultancy for the party. What’s missing is 70 to 80 percent of those “marginalized” groups who happen to be working people.

So the Democrats are the party of race, the party of gender — but race and gender as conceptualized by their elite strata. That’s the historical trajectory. And that’s why, within the party, they leaned on this distorted legacy, because it was a form of race politics that fit with elite black interests.

Melissa Naschek: Can you explain further what the civil rights movement was fighting for and why this vision of racial justice didn’t survive the 1960s?

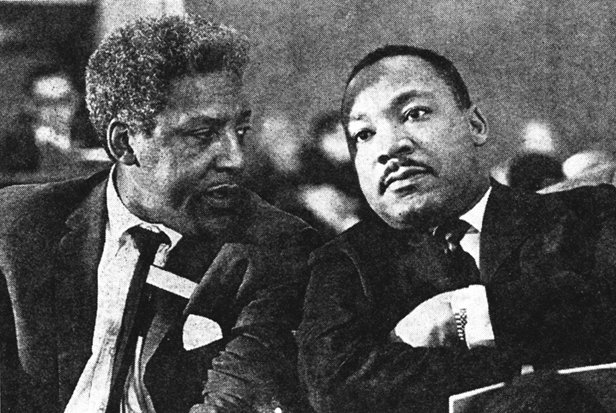

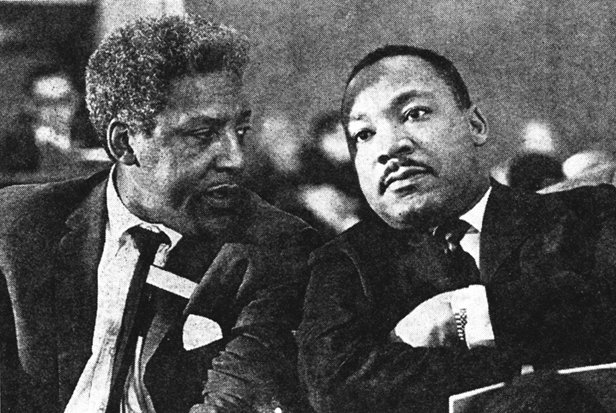

Vivek Chibber: This is a very good example of two different ways of approaching the question of race. The version that has been buried was in fact promoted by Martin Luther King Jr himself and his main lieutenants, especially A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin. Both of them were crucial in pushing for an agenda in the civil rights movement that went beyond simple political rights to insist on what you might call economic rights for black Americans. And famously, the March on Washington was a “march for jobs and freedom,” not just for political equality.

Randolph wasn’t an isolated figure in the trade union movement in his insistence on achieving racial justice through economic demands. The CIO had been pushing this since the 1930s and 40s, and it was very deep inside the Democratic Party by the ’60s.

Why did it go so deep into the party? Not because elite blacks were pushing it, not because black electorate politicians were pushing it — there weren’t that many of those. It was because black workers were able to find a voice for themselves and some political influence through the trade union movement. The CIO probably did more than any other political organization for working-class black Americans.

It wasn’t just Randolph and Rustin but also King. It’s important to remember King came out of the Christian socialist tradition himself. All of them insisted then that the anti-racist agenda has to also be an agenda of economic redistribution, of having jobs, of having housing, of having medical care. It must be this broad agenda.

Now, two things happened here that were crucial. There isn’t a lot of scholarship on this, so we have to rely on anecdotes and what little analysis there is. But Bayard Rustin famously said that, after the Voting Rights Act was passed, the black middle class largely dropped out of the movement.

Why did that happen? Probably because they had got what they wanted — they got the ceiling on political participation lifted. They had the promise of political equality. But if we turn to economic demands, they were much less interested. They already had decent economic resources. They were much less interested in fighting on that front. But these were the very issues that were really pressing for the vast majority of black Americans — housing, medical care, employment, decent education. And none of this could be achieved without economic redistribution.

The problem that Rustin and King face after 1965 is not just that the black middle class drops out of the movement. The problem is that once you change the focus from political rights to economic redistribution or economic expansion, the degree of resistance from the ruling class also changes. Capitalists will be more likely to give you political rights because that doesn’t directly affect their economic power. But once you start making demands that actually require economic resources, the resistance is also going to be greater, which means your strategy has to change.

So the problem is, first of all, that one chunk of your movement — the black middle class — has dropped out just when the resistance from the business community is going up. Your coalition has narrowed. Second of all, there’s no way a fight for redistribution will ever be won by the black working class alone. Even if you could organize all the black workers, the fact of the matter is that, in 1965, black Americans comprise around 12 percent of the population. It’s a very small minority of workers going up against the most powerful ruling class in the world. In order to have any chance of succeeding against this class, to the point where they’re willing to give you your economic goals, you also have to bring in the white working class. There’s no way around it.

So even if all you’re worried about is the fate of black Americans, you have to turn it from a black movement to a poor people’s movement. Because if you don’t bring in the white workers, your race goals will not be met. That’s what King realized. Even if you’re just concerned about race justice, you now have to be a universalist. You have to be somebody who puts class politics as the instrument toward race justice.

But they come to this realization at the worst possible moment. The unions are starting to go into decline, progressive forces are on the defensive, austerity is setting in. Eventually, the black elites take over. Up until the mid-1980s, the Congressional Black Caucus was still a somewhat social democratic force. But after the ’80s, black politicians largely become beholden to corporate interests themselves.

By that point, the King-Rustin vision of race justice has been replaced by the black elite and the black middle-class version of race justice, which leaves black workers, and later Latino workers, out of the picture altogether. And you get what we today call identity politics.

Read the entire interview here.