The social media environment inverts our deepest wisdom

I remember the most mortifying moment of my undergrad career, and it wasn’t the time I told Eric Miller I was becoming an anarchist after a bad breakup. It did, however, happen in his class—freshman humanities at Geneva College, circa April 2009.

All semester we’d been covering Dr. Miller’s blackboards before class with snippets of poems or lyrics or favorite quotes from books and movies that had to do with whatever topic was under discussion. Now it was the last day of classes before summer break, and the blackboard graffiti tackled that theme. I made my contribution: “Summertime, and the living’s easy”—credited to Sublime, the 90s ska/punk band.

In my defense, it is a line from Sublime’s “Doin’ Time.” To my eternal chagrin, I had absolutely no idea that the line was originally Gershwin’s, from Porgy and Bess.

I wasn’t musically illiterate either. I was nineteen years old and in my rock-music-rebel phase—that was the year my contribution to our dorm floor’s mix-CD of everybody’s favorite songs was Blue Öyster Cult’s “Don’t Fear the Reaper.” But I had taken years of music lessons and had been the piano accompanist for my church since I was twelve. I also had a surprisingly deep well of knowledge of seventies pop, thanks to a summer job as a dishwasher at a retro diner.

But somehow, inexplicably, there was this gaping hole in my musical education. I didn’t know what I didn’t know until another student looked at my defiantly nonconformist punk rock lyric scrawled on the blackboard and said, “Wait, isn’t that Gershwin?”

“Yes, I know,” I said, too proud to admit that I didn’t. “I’m specifically referencing the Sublime song.”

I’m still thinking about that moment fifteen years later. I still live in that fear—that sooner or later I’ll inadvertently reveal some other unknown gap in my knowledge in an embarrassingly public way. It’s a fear I feel very keenly because, like it or not, I have a public platform these days—a small one, but a publicly visible one nevertheless. One of the first things my agent asked me to do when Macmillan acquired my first manuscript was to start an Instagram account. I’d resisted until then. But as an author, especially as an author of fiction for teens, it was an expectation.

Social media has shaken up the book industry in ways we’re still struggling to understand and absorb. Books become bestsellers these days by going viral on TikTok: Walk into Barnes & Noble, or even your local library, and you’re likely to see an endcap display dedicated to the latest “BookTok” hits. It’s still possible to sell a novel to a major publisher without having a big social media following or name recognition, but publishers are absolutely paying attention to what’s trending on social media and making acquisitions decisions and allotting marketing budgets accordingly.

There’s another essay to be written about the vicious cycle this has created: If publishers are increasingly acquiring books tailored to social media algorithms, then that’s what authors who want to sell a book to a publisher are increasingly going to write, which inevitably means fewer stories that take creative risks and break molds.

But that’s for another day. My point is that authors are under a lot of pressure to build an active online platform. At the very least, this usually includes a website, a newsletter, and multiple social media profiles with regular, engaging posts. My writer friends feel guilty for taking social media breaks to focus on writing (!) because they know that their publishers expect them, sometimes contractually, to be active online.

There’s an irony here: Book publishing is a notoriously opaque industry that has historically benefited from authors’ silence. A few years ago Black author L.L. McKinney started a viral hashtag campaign, #PublishingPaidMe, that encouraged authors to publicly reveal their book advances. The campaign exposed some of the huge disparities between advances paid to white authors and those paid to BIPOC authors. As a result of #PublishingPaidMe, a few publishers pledged to do better at addressing in-house racism cloaked until then by a culture of silence.

“Silence encourages the tormenter, never the tormented,” said Elie Wiesel in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech. We know this. We know the historical damage done by silence. It’s a good thing when public figures, especially those who enjoy the privileges of the system, use their platforms to raise awareness of oppression and injustice at home and abroad.

But if silence allows injustice to run rampant, what happens on the flip side? What about the damage done by people who don’t know when to stop talking?

I’m not talking primarily about chaos agents intentionally sowing disinformation, though that’s a real problem. (Think of what happened in Springfield, Ohio just a few months ago, when racist lies spread on social media escalated to bomb threats and school closures.) I’m talking about people with good intentions and big platforms, weighing in on things they don’t know very much about because, for whatever reason—publishers, peers, audience, social media algorithms that reduce the visibility of accounts that aren’t consistently active—they feel an obligation to speak.

Take the Russia-Ukraine war, which became a hot-button issue in February 2022. The war had been ongoing for eight years at that point, but suddenly it was time for people in the West to have opinions about it. And it quickly became obvious that many of them had little to no understanding of the historical background, the realities on the ground, or the damage that misinformation can do in the context of genocide. In the book community, Elizabeth Gilbert’s decision to pull her forthcoming Russia-set novel out of sensitivity to her Ukrainian readers led to some ugly, now-deleted outbursts on social media from a few big-name writers. But, more to the point, it revealed that these writers—literary tastemakers, many of them, with bestsellers and bylines in major publications—had never before paid any attention to Ukraine. And yet they felt qualified to offer opinions, and their takes—however misinformed—shape other attitudes in the book community in turn.

If you don’t know what you’re talking about, it’s usually much better to say nothing at all. But that’s not the social media environment we inhabit.

In this new year I want to do better about remaining silent, no matter how hard it may be—and I have a feeling it’s going to be pretty hard sometimes. I want the humility to acknowledge when I don’t know enough about a topic to speak on it, even when I feel there’s an expectation for me to speak. My platform is bigger than it was in that classroom in 2009. My ignorance can do that much more damage.

Silence isn’t—or shouldn’t be—the same as inaction or complacency. Along with silence comes the work of educating myself, seeking out and listening to the people who do know what they’re talking about, and amplifying them instead. But silence is the first step.

Amanda McCrina writes historical fiction about Poland and Ukraine during World War II and the Cold War, inspired by her own family’s heritage. Her latest is I’ll Tell You No Lies (FSG, 2023). She lives outside Nashville, Tennessee.

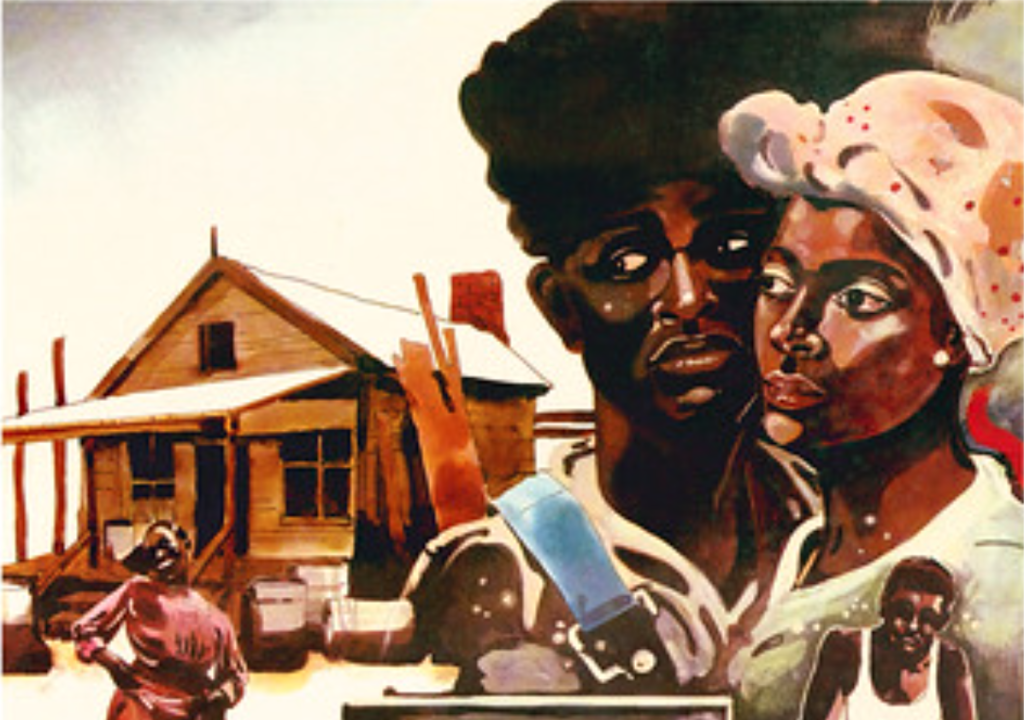

Image credit: Ivan Jullien Big Band – Porgy And Bess album cover Label: Blue Star – House Of Jazz (2) – Vol. 7