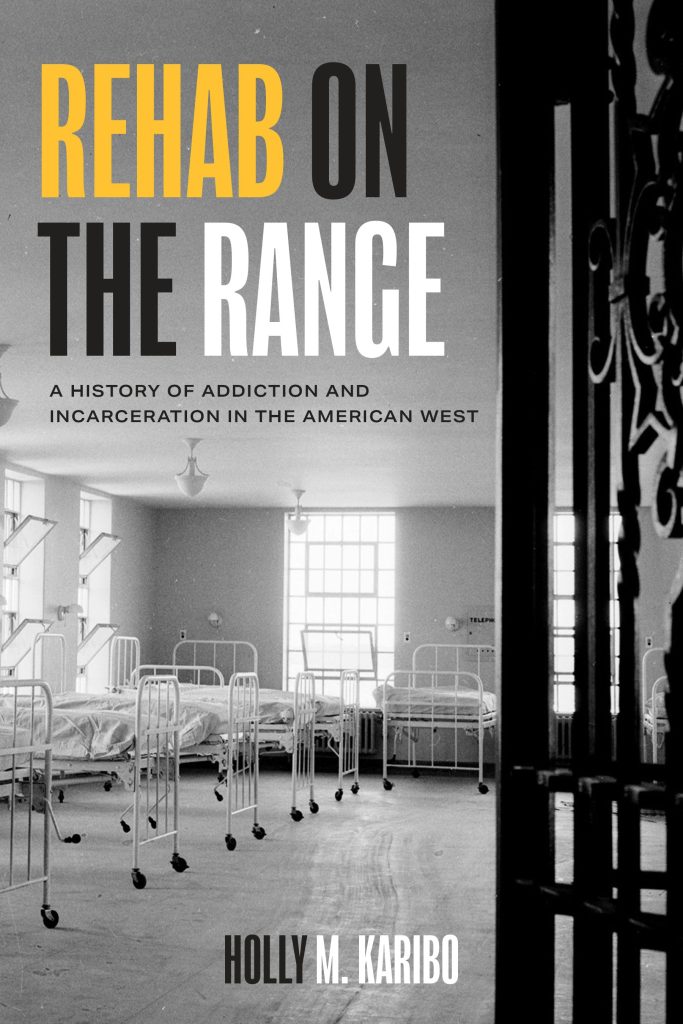

Holly M. Karibo is Associate Professor of History and Director of Graduate Studies at Oklahoma State University. This interview is based on her new book, Rehab on the Range: A History of Addiction and Incarceration in the American West (University of Texas Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write Rehab on the Range?

HK: I am a social and cultural historian whose research focuses on the history of borderland communities, vice, and moral regulation in North America. Through these themes, I became interested in the history of drug control, addiction, and using communities. I’m also particularly interested in uncovering the local and regional histories around me. These interests all came together when I began my first full-time teaching position in north Texas. I was reminded that Fort Worth was home to one of only two federally funded drug treatment institutions in operation in the US between the 1930s and 1970s. When I began to dig into the literature, though, I quickly realized that the only work that had been written on what were known as the “narcotic farms,” focused on the Lexington Narcotic Farm. The Fort Worth Narcotic Farm was virtually absent from the scholarship or was only mentioned in passing. Since these institutions were designed to treat addicts along geographical lines (the Lexington Narcotic Farm largely treated users living east of the Mississippi River, while the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm treated users living west of the Mississippi), I also became interested in how the western institution was embedded in broader drug markets and using patterns that developed in the US West during the mid-twentieth century. I started with a trip to the National Archives at Fort Worth, anticipating that I might find enough material to write a short piece on the institution. As I began digging into the records, it seemed clear that there was much more to the story of the Texas institution. It was not simply a smaller ‘sister institution’ of Lexington, as it’s so often been framed. Instead, I began to see it as a vivid window into much larger developments affecting the US West during the mid-twentieth century, and how imprisonment and addiction treatment affected communities living on the nation’s margins.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Rehab on the Range?

HK: Rehab on the Range argues that US federal drug treatment policies that developed between the 1930s and 1970s were deeply intertwined with concepts of punishment and the rise of the nation’s prison system. This was especially true in states on the national border, which often bore the brunt of crackdowns on drug users and addiction during the mid-twentieth century.

JF: Why do we need to read Rehab on the Range?

HK: Rehab on the Range documents the roots of several critical issues that continue to dominate US politics and culture. That includes our ongoing struggle to determine how to approach drug use and addiction: what is the role of the medical profession, and what is the role of the criminal justice system? The narcotic farm model was designed to provide a combination of psychiatric care, physical rehabilitation and vocational training all within an institutional setting. The idea was that they would provide an alternative to imprisonment for both federal drug law violators and voluntary addicts. And yet, as I document, the carceral features of the institution came to undermine its therapeutic objectives. In many ways the debates over the narcotic farms that unfolded between the 1920s and 1970s sound frustratingly similar to the debates we continue to have today. Tracing what was successful and what failed in the narcotic farm model can perhaps offer us a different path forward. The book also resonates within a political environment that calls for increased crackdowns on national borders as a way to stem the flow of drugs into the country. Yet, as numerous earlier attempts to focus on supply over demand make clear, these ‘tough on crime approaches’ are often at best temporary solutions, and at worst further deepen the nation’s commitment to mass incarceration. Rehab on the Range documents some of the unintended and personal costs of these public policies.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

HK: I’ve always been fascinated by history—whether that was the local history around me, or national and international histories. For me, history is a form of storytelling, and in that way, it is very much about human drama. It sounds a bit cliché, but early on I had some amazing history teachers that helped inspire me to see the connections between the past and the world we live in today. As one example, as a teenager I became a Woody Guthrie fan, and was drawn into the stories told in his songs. Growing up in Michigan, I was especially fascinated by “1913 Massacre,” and set out to see if it was in fact a true story. My high school history teacher, Russell Cannon, helped me dig into what turned out to be an actual historical event, and it got me interested in labor politics, power struggles, music, and the Great Depression. I suppose there was no going back from there. In college, I learned the different paths that could help me turn my interest in history into a career. During my graduate training at the University of Toronto, I began to study US history from a transnational perspective, and to think outside the neatly defined national boundaries that have long shaped the discipline. In this way, I think of myself as a ‘North American historian,’ as I’m particularly interested in national boundaries and the way they are contested by those who cross them.

JF: What is your next project?

HK: I’m currently serving as the Fulbright Canada Research Chair in Canada-US Relations at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada. During my time, I’ve begun a new research project titled, “Ladies, Liquor, and the National Line,” which traces the history of women involved in bootlegging and the illegal liquor trade along the US-Canada border during the US Prohibition years. Moving us beyond the well-known narratives of violent male bootleggers and female moral reformers, my study traces how various women contributed to the illegal alcohol economy during American Prohibition; the diverse roles they played at all levels of these industries; and how the growing number of women involved in smuggling reshaped efforts to police and regulate the national line during the 1920s.

JF: Thanks, Holly!