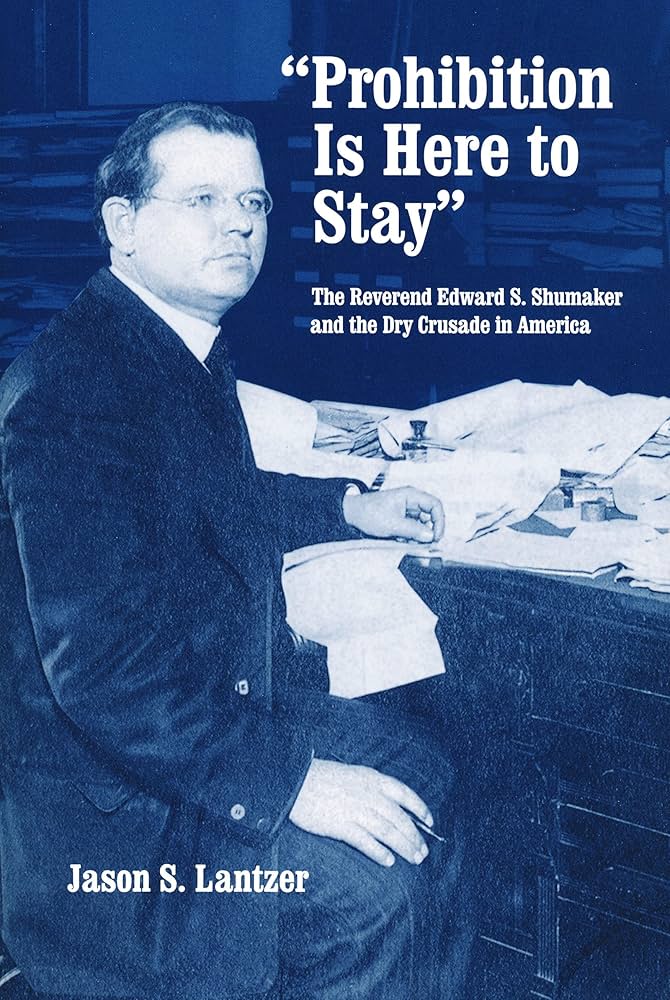

Jason S. Lantzer is Assistant Director of the Butler University Honors Program. This interview is based on his new book, “Prohibition Is Here to Stay”: The Reverend Edward S. Shumaker and the Dry Crusade in America (University of Notre Dame Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write “Prohibition Is Here to Stay?”

JL: Prohibition is Here to Stay: The Reverend Edward S. Shumaker and the Dry Crusade in America began life as my doctoral dissertation at Indiana University. I was interested in exploring some avenue of American Religious History and had several ideas. While discussing those options with my academic advisor, Professor James H. Madison, he suggested that I consider the intersection of the Methodist Church, the Republican Party, and the Second Ku Klux Klan in Indiana during the 1920s, as this was something that was missing in the scholarship of Indiana/Midwestern History (which was also an area of interest to me). Jim’s suggestion got me into a church archive in Indianapolis, which led to an award-winning essay about how the Methodist Church had largely forgotten/neglected its work as part of the temperance reform movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. That essay got the attention of a retired faculty member at DePauw University, who put me in touch with another retired professor from that institution, Arthur Shumaker, who was the son of the Reverend Edward S. Shumaker, a Methodist minister who led the Indiana chapter of the Anti-Saloon League for over two decades. As it happened, Arthur had all of his dad’s papers, which had never been looked at before, and gave me permission to use them. Suddenly what might have been just a study about the topic of church/state relations and reform became personified in the story of Shumaker.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of “Prohibition Is Here to Stay?”

JL: Evangelical Protestants, like Shumaker, launched and took part in a series of reforms that sought to create God’s Kingdom on this earth. And while we may view their greatest effort in this spirt, the prohibition of alcohol, as a failure, not only was it an attempt to address very real problems in American society but that particular reform (as well as the wider effort) shaped and continues to do so, the nation (and world) we live in today.

JF: Why do we need to read “Prohibition Is Here to Stay?”

JL: There are several reasons. First, the conventional wisdom is that Prohibition was both misguided and a failure. The reality is much more complex. Dry laws were seeking to address very real problems and concerns, were widely popular (at least in theory), and that drinking decreased by perhaps as much as 80 percent. he popularity of the reform was such that other organizations (beyond say denominations and groups that advocated for it) utilized it for their own reasons–in the 1920s, the most obvious example of that was the Klan. In terms of advocacy, the Anti-Saloon League is often recognized as the first modern political action committee—and the League was formed and driven by Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Disciples of Christ (along with other smaller, denominations); they were very much the (Protestant) Church in action. But it was not just supported by white evangelical Protestants; African-American denominations also supported the dry cause and so did some (though certainly not all) Roman Catholics. Discussing groups such as these further complicates our understanding of Prohibition as some sort of effort at control or one that was merely symbolic in nature. Furthermore, even when repeal came, understanding Prohibition also helps us better understand and appreciate the early New Deal–as well as the web of alcohol laws that emerged from its demise, plus providing insight into what denominations seemingly disengaged from direct political activity. I could go on, but if I was going to sum it up, it is that we do ourselves a very real disservice if we don’t have a good understanding of the greatest attempted reform of the first half of the 20th century–which included countless laws at the local, state, and national levels, as well as not just one but two amendments to the US Constitution.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

JL: History was always my favorite subject. I grew up reading about World War II, the Civil War, and just about every book and biography I could get my hands on starting in elementary school. Not only did have I have excellent teachers at every level who nurtured that interest, but I had parents who indulged it. When I headed off to college, the first in my immediate family to do so, there was little doubt that I was going to major in History and Political Science. But it was not until my junior year at Indiana University Bloomington (I am not just a native Hoosier, but a three times graduate of IU) while taking a history course with the late Irving Katz that I decided to make History my profession. One day in class, Professor Katz gave us a mini lecture at the start of class about why History was the perfect discipline. It was if a light bulb went off as I sat in that classroom–I suddenly knew that I didn’t want to go to law school, I wanted to go to graduate school, because what I loved was History and what I wanted to be was an historian. It was, of course, while I was in graduate school where I learned what that actually meant (and so, am indebted to my professors at that level as well—including Bob Barrows, David Bodenhamer, Art Farnsley, Stephen Stein, Claude Clegg, and of course Jim). I have not looked back since!

JF: What is your next project?

JL: I recently published a book on how encountering the Holocaust impacted Dwight Eisenhower, both as a general and then as president and am now working on digging into that topic further. Additionally, I am part of the Congregations and Polarization project, which is midway through a study of how cultural polarization, congregational sorting, and rural/suburban/urban locales is affecting religious organizations in the wake of the pandemic and the 2024 election cycle. I’m also helping out a local congregation as it compiles its 175th anniversary history. Oh, and there is always something more to do with Disney!

JF: Thanks, Jason!