Learning from the textbook of the community

Progress Notes: One Year in the Future of Medicine by Abraham M. Nussbaum. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024. 408 pp., $29.95

Progress Notes is about a new solution to an old problem. It follows Dr. Jennifer Adams and seven of her students at the University of Colorado Medical School as they navigate a curriculum designed to help doctors-in-training see their patients more holistically, understand American healthcare more critically, and nurture their own sense of calling.

The longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC) originated in the early 2000s when Harvard Medical School professors David Hirsh and Barbara Ogur began to worry about their students succumbing to exhaustion and apathy. They suspected that contemporary medical education, with its focus on mastering the parts and processes of the body along with their attendant specialties, kept students from participating in the lifegiving act of caring for whole people. Hirsh and Ogur proposed that instead of spending their third year rotating through specialties, medical students should follow individual patients for the entire year (hence longitudinal) from appointment to appointment across the specialties (hence integrated).

In this model, the patient, rather than the organ or the medical modality, serves as the organizing principle for medical education. Hirsh and Ogur hoped this approach would enable students to “reconstitute holistic understandings of people” and equip them to “become agents of change for a return to a more effective, humanistic, and fulfilling practice of medicine.” The LIC has since spread around the world.

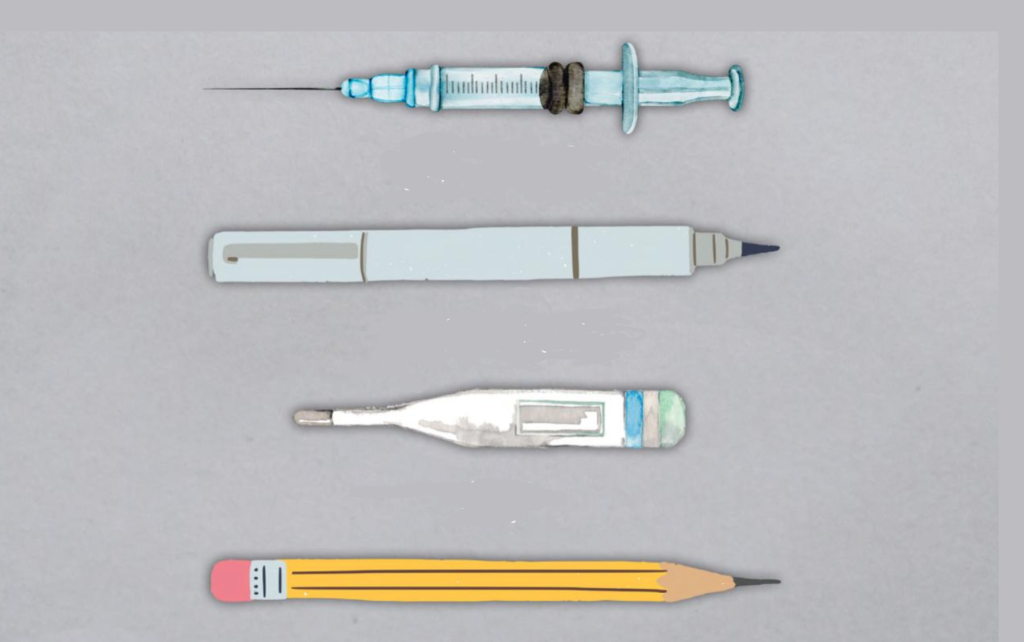

Abraham M. Nussbaum describes the LIC as an attempt to teach students the “textbook of the community” in addition to the “textbook of the body.” The textbook of the body is best illustrated by the first thing students do upon arriving at medical school: dissect a corpse. The cadaver lab teaches students to see patients as so many normal or abnormal components, providing them with their first lesson in the reductive tendencies of modern medicine. The famed Johns Hopkins University professor William Osler pioneered this science-focused approach at the turn of the twentieth century, and thereafter reformers like Abraham Flexner ensured it became the standard that shaped American medical education for a century.

The textbook of the community, by contrast, encourages medical students to see patients as whole people embedded in broader worlds. By following patients for a year, LIC students get to know them and their families. They learn about their lifestyles, their ambitions, and their struggles. They begin to understand not only their afflictions but also the barriers they face as they seek medical care and attempt to live healthier lives.

The fear that progress in the medical sciences distorts both practitioners and the care they render has a long history in the United States. In the early nineteenth century, as dissection became the preferred method for learning anatomy, many people worried that repeatedly cutting open dead bodies brutalized the sensibilities of dissectors and diminished their view of human life. Writing in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1854, theologian Tayler Lewis shuddered to imagine “the sacred human body, the once loved form, the former temple of a loving spirit, thus lying mangled, debased, deformed, made the subject of unfeeling remark by some cold materializing lecturer.” He feared that “the air of the dissecting-room is unfavorable” to belief in resurrection. That medical students—with help from their professors—robbed the graves of the poor, friendless, and enslaved and played irreverent pranks with their bodies only seemed to confirm the depravity of dissection.

At the turn of the twentieth century, when both medicine and major life events began to move into the hospital, fears of the cold, unfeeling, and reductionist impulse of medicine reappeared. Free people of means had long experienced birth, death, and medical care at home. But urbanization driven by industrialization cut people off from kin, forcing them to seek care in the growing number of city hospitals. At the same time, the new requirements of antiseptic and aseptic surgery, along with the broader cleanliness mandate of germ theory, made those hospitals austere and less homelike. As one observer lamented in 1907, “At no point in his hospital career is [a patient] looked upon as anything but a medical subject. He enters the hospital because he is sick, he is treated as a phenomenon of medicine and surgery, and is discharged as ‘cured,’ ‘improved,’ or ‘no hospital case.’ His social status, one might say, is studiously ignored.”

The scientific, technological medicine of the modern hospital only grew more powerful in the coming decades, augmented after midcentury by antibiotics and the expanding pharmaceutical arsenal. But the counterculture years witnessed more waves of critiques. Some complained that healthcare was becoming ever more expensive even as it excluded the poor and people of color from its benefits. Some questioned its benefits altogether, as when Ivan Illich characterized medicine itself as harmful in Medical Nemesis (1975). Others focused on what medicine had lost. “Most physicians have lost the pearl that was once an intimate part of medicine—humanism,” Dr. Frederick Stenn wrote in 1980. “Machinery, efficiency, precision have driven from the heart warmth, compassion, sympathy, and concern for the individual. Medicine is now an icy science.” Reforms within medicine, like the development of the biopsychosocial model, and the surging popularity of alternative therapies testified to the pervasive sense that what was now termed biomedicine had lost its soul.

The LIC is thus another foray in an old and enduring struggle. But the LIC also has its own particular battles to fight. In part, it combats specialization. Across the twentieth century, after Osler developed the residency system, specialties waxed while general practice waned—so much so that in 1969, the American Medical Association approved family medicine as a specialty intended to counteract the ascendance of specialties. Critics blame this specialization for teaching practitioners to see parts rather than wholes. The LIC therefore trades the clinical year organized around specialties for one organized around patients, hoping to refocus medical attention on the integrated person. LIC students follow patients through an entire course of treatment, whether from pregnancy to birth to the pediatrician or from surgery to rehab to home. In this way, the LIC harkens back the traveling family doctor who, before the rise of modern hospitals, cared for families in their homes and across their lives. Indeed, LIC students are more likely than other medical students to choose primary care practice.

The LIC is also an attempt to restore to medicine its awareness of patients’ contexts—to resocialize medicine. In so doing, it builds on several generations of scholarship illuminating the social determinants of health. It teaches students to see not only ailments, but also the often-inequitable circumstances that produce ailments—to see the tight budgets behind poor nutrition, the broken sidewalks behind sedentary lifestyles, the lack of transportation behind missed appointments. Convicted by these insights, one LIC student added public health to her training and political advocacy to her vocation.

As much as the LIC is about teaching medical students to better understand their patients, however, it is also about helping them survive and perhaps even thrive in a daunting profession. After all, Hirsh and Ogur believed not that medical education discourages students and reduces patients, but that it discourages students because it reduces patients. It demands students sacrifice so much—their time, their health, and their relationships—not for the sake of their patients but for either deracinated science or the empty profits of corporatized healthcare.

The doctor and writer Anna DeForest captured the cynicism that befalls medical students in her novel A History of Present Illness. “It was rare, outside of personal statements,” the medical student narrator confesses, “to find many students who believed this work was a calling.” Nussbaum therefore devotes most of his attention to the LIC students themselves. He follows them as they discern their medical interests, marry and divorce, fret over school loans, have kids and delay kids, get sick, and dream of bright futures. He hopes the LIC will help them endure the rigors of medical school with their sense of purpose intact. “We need a system,” Nussbaum says, “that enchants again and allows physicians to truly flourish, to realize their potential by caring well for patients.”

The book ends on a mixed note. Nussbaum accompanies the students as they move from the LIC to a year of advanced training in their chosen specialties and then to the final triumphs of graduation and matching with residencies. But those celebrations happen over Zoom amidst COVID-19 shutdowns. The pandemic taught hard lessons. After the early heroic days—the days of marching to work to the soundtrack of the clanging pots and pans of cheering neighbors—doctors confronted the sobering realization that the crisis called not only for heroes but also for structural change. Like so many previous scourges, COVID-19 traced the lines of existing inequalities, visiting disproportionate suffering on already disadvantaged people.

Individual sacrifice alone could not solve this problem. Ironically, it was in the LIC that students learned that clinical care accounts for only a small portion of patient health outcomes. So, how much could improving the medical education of future clinicians accomplish? Nussbaum acknowledges the limitations of curricular reform but he believes the LIC is a good place to start. At the end of the book, he announces that the LIC will no longer be just one possible clinical year track at the University of Colorado Medical School; it will now structure the entire four-year curriculum for all the students. Maybe giving all physicians new eyes to see will change things.

The medical profession, with its immense wealth and lobbying muscle, wields enormous power in American life. It has often used this power for conservative ends, whether excluding Black doctors or advocating against so-called socialized medicine. Nussbaum hopes more humanely trained practitioners might become what nineteenth-century German physician Rudolf Virchow believed they could be: “the natural attorneys of the poor.” With changed hearts, they might change the system that produces so much burnout, alienation, and inequitable suffering. They might learn, as Nussbaum concludes, “that individuals are well only when the community is well.”

Jonathan D. Riddle studies the intersection of medicine and religion in United States history. He is an assistant professor of history at Pepperdine University, where he also directs the health humanities minor.

Really fascinating! Thanks!