We must cultivate the setting for a better politics

Donald Trump was quick to claim that Republican success in the 2024 elections marked a “historic realignment.” If a realignment means the beginning of a period in which one political party gains the support of a reliable electoral majority, then there is reason to be skeptical about Trump’s boast. But his boast shouldn’t be ignored: It prompts reflection on the sources of the hollowness of American political life and our responses to it. It has been sixty years since one party held the presidency along with bicameral congressional majorities for eight years at a stretch, and ninety years since a party has had such a governing streak for longer than eight years. Absent a realignment, citizens will continue to suppose that representative politics means no more than posturing and mutual obstruction. Trump’s not alone: We are all waiting for a realignment.

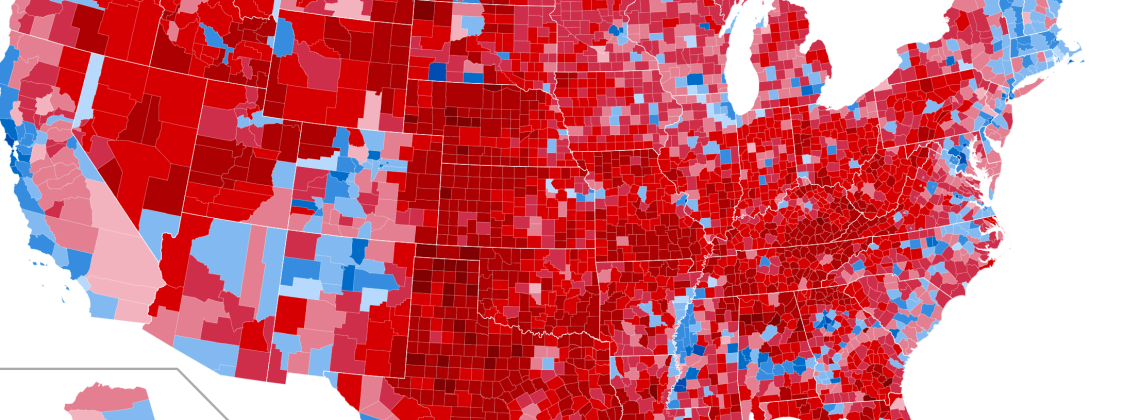

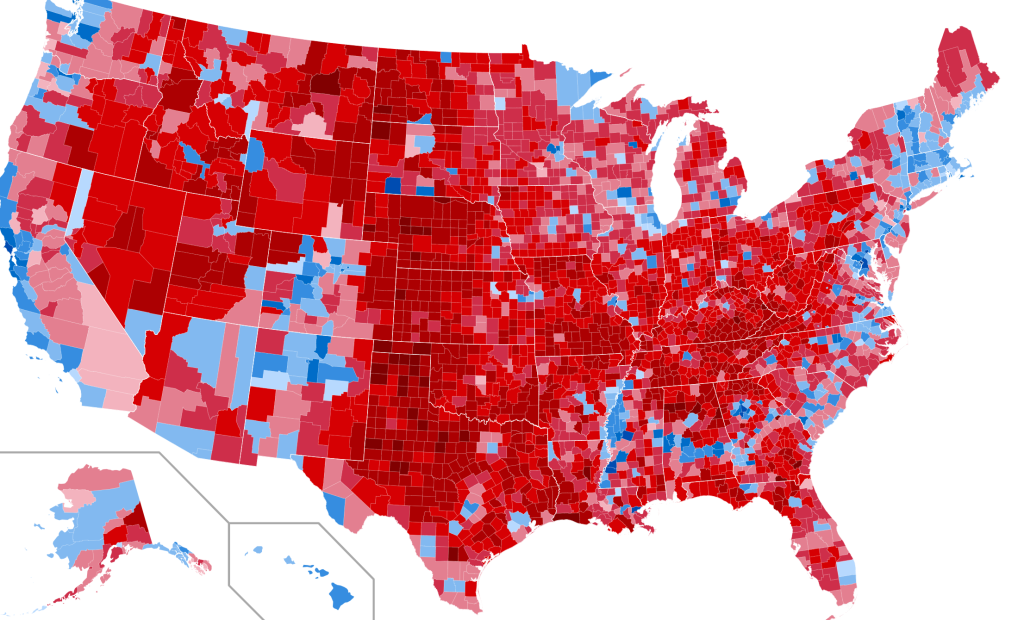

A party realignment brings a measure of electoral stability. But this year’s Republican victory looks more precarious than auspicious. Trump received the second-lowest popular vote percentage for any winning presidential candidate since 2000 (the lowest was, of course, for Trump in 2016), while Republican candidates won a Senate majority of unexceptional strength and the slimmest House of Representatives majority since the days of Herbert Hoover.

Once in office, the Trump administration will be fraught with contradictions. At the Republican convention, J.D. Vance declared: “We’re done, ladies and gentlemen, catering to Wall Street. We’ll commit to the working man.” Yet Wall Street will be well represented in Trump’s Cabinet. Trump voters were motivated more by frustration with inflation than by hostility to immigrants. Yet a massive round-up of the undocumented—necessarily entailing both enormous expense and overt cruelty (not to mention a disrupted workforce)—remains the sine qua non of the MAGA agenda. The more Trump pleases one portion of his supporters, the more he will betray another. Even his adept showmanship may not suffice to make the pieces look like they fit together.

There are many paths by which Trump’s administration may shrink the Republicans’ base of electoral support and few by which to expand it. Democrats may soon have another chance to assemble an electoral majority of their own. How? The suggestions coming from various sources converge on common themes: run working-class candidates, emphasize jobs and income, use sharper language attacking economic elites, talk differently (or just less) about polarized social issues. Democrats should, in other words, campaign better.

These are smart ideas. But it is worth noticing what this advice assumes: That outside of a brief moment in the voting booth a citizen is a passive recipient of messages of political campaigns, that party realignments are achieved by optimal campaign techniques, that a realignment’s purpose is to empower a particular set of political professionals. There are better ways to think about the nature and purpose of realignment.

Sixty years ago, the term “realignment” gained currency among civil rights and labor organizers. Shortly after the 1964 elections, Bayard Rustin—the logistics coordinator for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—argued the Johnson landslide could herald a long-term Democratic majority if civil rights activists and their allies moved “from protest to politics.” Rustin wanted “the coalition that staged the March on Washington” to become, for the Democrats’ electoral majority, something like what a core is to a tree: both the form-giving structure and the communicator of liveliness.

Electoral analysts today use the word “coalition” to mean an assortment of citizens from a variety of demographic groups. For Rustin, however, the word indicated a self-aware alliance among associations: civil rights organizations, labor unions, religious groups dedicated to social justice. Rustin’s kind of coalition is a set of relationships, an engagement in large-scale politics mediated through small- and medium-sized membership-based organizations constituted by forums for speaking and listening and by bonds of trust and solidarity.

Rustin’s model of party realignment is more attractive than the party realignment that both Donald Trump and the Democrats’ post-election advisors have in mind. What is won through message-craft and spectacle can be just as quickly lost through message-craft and spectacle. An electoral majority achieved purely via the campaign savvy of political elites, without a coalition of citizen organizations at its center, is likely to be so ephemeral that achieving it would barely register as a realignment.

What’s still more interesting about the older idea is its sense of what a realignment is for. If, as Rustin hoped, a coalition of citizen organizations becomes the political force that swings parties into a new alignment, then a realignment isn’t merely a reshuffling of political professionals’ opportunities for power. Instead, it’s a deeply democratic event, a reshuffling of citizens’ opportunities—both locally and on larger scales—to find common ground with one another.

But that older vision of party realignment depended on a flourishing organizational life that no longer exists. We have more advocacy offices than movements; labor unions and religious congregations alike struggle against membership decline; our civic life has shifted, as Theda Skocpol aptly puts it, “from membership to management.”

Is a party realignment—one worth having, anyway—out of reach? It would be tempting to stop here with a call to renew membership-based organizations, to map out a political plan in which an organization-building step precedes a party-realigning step, as if the kind of politics we saw in this year’s election campaigns—record levels of advertising spending, increasing dominance of online media—could, by will-power and shoe-leather, be replaced by a human-scaled politics of meetings and conversations. Some willful movement in that direction would be good. But there is reason to be skeptical about the pridefulness of that reliance on the will.

As Skocpol and her student Lainey Newman show in Rust Belt Union Blues—an essential book for understanding the political context of the 2024 elections—organizational membership is easier to increase, easier to sustain, and more consequential for how group members perceive themselves and the political sphere when a community includes an array of organizations with overlapping memberships and interfused purposes. As important as the decline in American organizational life may be, the decline of densely connected communities matters too. We need to organize and to keep our organizations going. But we also need ways of living together that can recover or reinvent for our time some of the fruits of the civic cohesion out of which previous generations’ organizational lives grew.

I want to suggest that we think of organizational life as the best setting for electoral politics, and community life as the best setting for organizations. Each of these elements of political life functions better and gains a clearer sense of its proper purposes when it is embedded in something more fundamental than itself. The lesson of the older vision of party realignments is that citizens need to concern themselves with all these layered settings.

To orient such slow and subtle work, we need not so much a strategy for aggregating power as an ethic of presence and connection. Out of what is that ethic to grow?

Edwin O’Connor’s 1956 novel The Last Hurrah—the greatest American literary examination of electoral politics and, not incidentally, a perceptive story about the organizational and civic settings of electoral politics—offers what may be a surprising answer. Frank Skeffington—long-time mayor of a big Northeastern city, captain of a well-tested political machine, self-declared “tribal chieftain” among his city’s Irish Americans—is shown dispensing favors to constituents, politicking at a wake, and lambasting his opponents in delightfully venomous speeches. But as the novel begins, before we see Skeffington doing those things, we see him alone.

Skeffington awakened early, as he always did; for half an hour he lay in bed, waking slowly, watching the first pale flush of daylight . . . He rose, said his morning prayers, and had his breakfast brought up to him . . . After breakfast he picked up a book and settled down by the long front bedroom window to read; this had been his morning custom for nearly fifty years . . . He read poetry for the most part, and he read chiefly for sound, taking pleasure in the patterns of words as they formed and echoed deep within his brain.

A good public life depends on a capacity for stillness, patience with silence, the willingness to let beauty form and echo within. I don’t know whether these things make for a more effective public life. Still, they are the proper setting for public life, the best soil in which the work of community-tending can be rooted. To practice that stillness—to foster the setting for the setting for a better politics—we do not need to wait for a realignment.

Geoffrey Kurtz teaches political science and urban studies at Borough of Manhattan Community College (CUNY). His recent essays have appeared in Front Porch Republic and Public Seminar.