The arc of the political universe is long, but it bends towards the common man

Near the end of the presidential campaign, when Donald Trump held a rally in Madison Square Garden, some likened it to the rally the pro-fascist German Bund held in 1939. This was the wrong historical analogy.

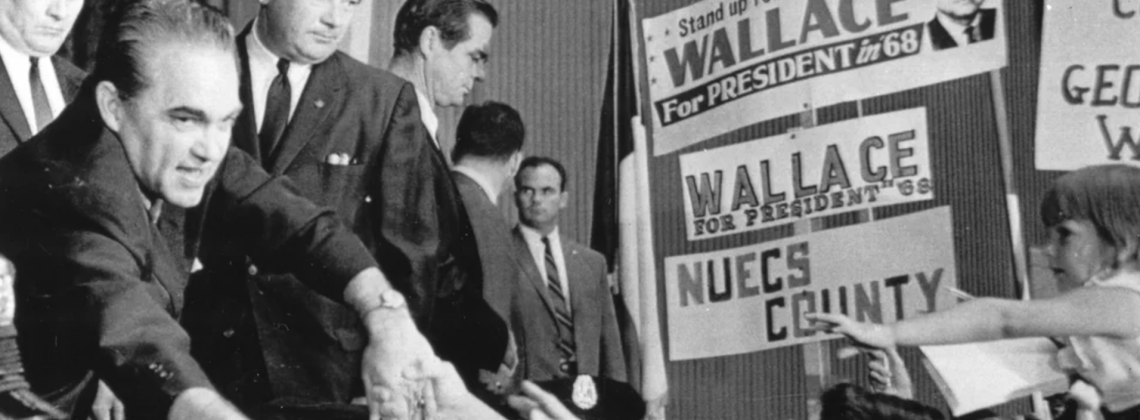

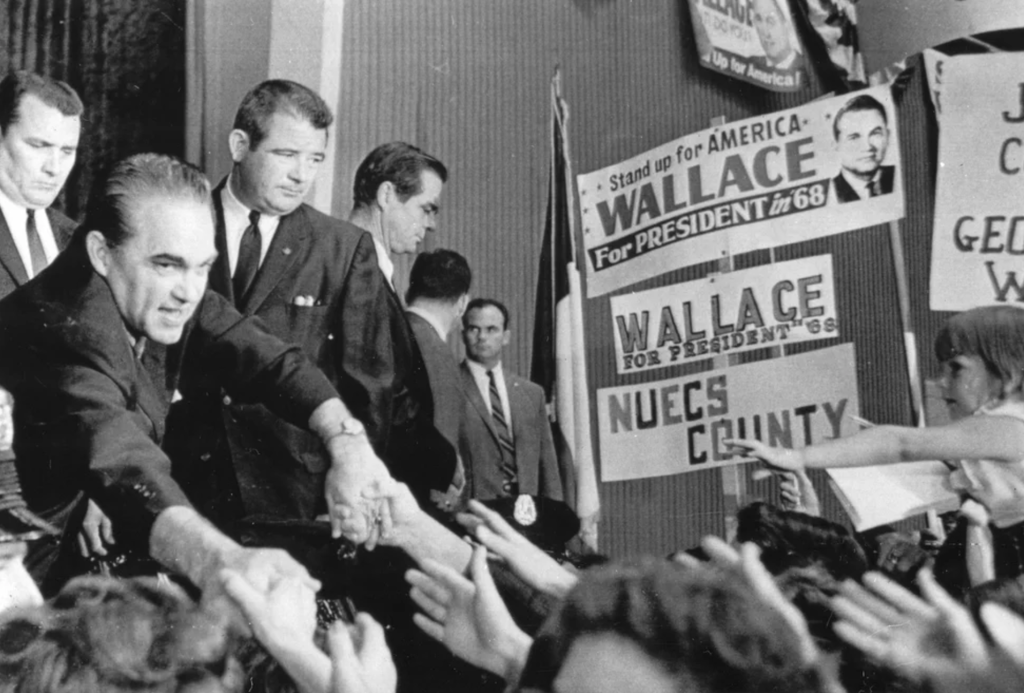

The right analogy is the rally George Wallace held at the Garden in 1968. Reading the speech Wallace gave then, I was struck by numerous parallels to Trump in 2024.

Wallace began by pointing out the local labor leaders standing with him. He claimed he had the support of regular working-class Americans. He repeatedly criticized the press for underestimating the size of his crowds and misrepresenting his views and record in Alabama. Criticizing the anarchy in the streets of America, Wallace denied that he was dog-whistling a racist message. The majority of “all races are against the breakdown of law and order.” Wallace attacked the left-wingers in both parties, and especially theoreticians, pseudo-intellectuals, professors and various experts “who look down their noses at the average man on the street.” These experts were telling Americans how to live, and Washington was issuing regulations forcing them to do what the “pointed heads” advised. He criticized NATO for not doing enough. He insisted that both parties had ignored the average Americans and that he was neither a fascist nor a racist for paying attention to them. He played on anxiety over gender issues, mocking a long-haired male heckler for looking like a “she.”

In light of Wallace’s career in Alabama politics, many called his comments at the Garden racist and fascist. Yet Wallace had originally been a moderate on race. Unlike others in the Alabama delegation to the 1948 Democratic convention, he did not walk out when the convention adopted a civil rights plank at the urging of Hubert Humphrey. He became an arch segregationist only after he lost to one in his first bid to become governor in 1958. Running as a segregationist in 1962, he won the governorship and became nationally known for opposing the desegregation of the University of Alabama. By 1968, however, he was no longer a segregationist—as a legal matter that fight was lost—but a populist, defending the common man of both races. Wallace was, above all, an ambitious opportunist.

Pollsters underestimated Wallace’s support among northern voters, pundits were surprised by it. He succeeded to the extent he did because he, unlike Republican and Democratic politicians, voiced the views of those most adversely affected by the great changes of the 1960s. Certainly, most of those he aspired to speak for were white. Many belonged to ethnic groups that had struggled to gain a foothold in the United States but had not been designated “protected” by the “pointy headed bureaucrats” running America. Consequently, they did not receive the preferential treatment dispensed to the protected. Did appealing to these voters make Wallace a racist? Many thought so and left it at that, thus missing what was happening in America.

Consider the advice given to another southern governor who ran for president in 1974—Jimmy Carter. Hamilton Jordan sent Carter a memo about his looming presidential campaign. Jordan advised Carter not to emphasize “the racial progress” theme in his campaign. “The groups of whites who have had to make the greatest sacrifices and adjustments in accepting racial integration are the working class men and women who have traditionally voted Democratic and are still having to cope with certain aspects of racial integration—busing, preferential treatment given some blacks in employment, etc.,” Jordan pointed out. If Carter talked about “racial progress,” he would remind working class people that they were paying the price for integration, earning their resentment rather than their votes.

While Jordan advised Carter to ignore the race issue to win white working-class votes, Wallace, in his effort to win, gave voice to those same voters. The two campaigns were dealing with the same dynamic—resentful working-class whites. Although least able to bear the cost of a necessary civil rights revolution, they were the ones paying it.

Wallace did not win, while Carter and Trump did. Why was that? Many reasons, no doubt, but a critical one was a change in the American political system following the Democratic convention in 1968. Hubert Humphrey, then Vice President, took the nomination without entering a single primary. He was selected by Democratic bosses and functionaries, prompting Democrats to adopt new rules to ensure a more democratic and representative nomination process. The result was the increasing use of primaries and caucuses. This gave unknown or insurgent candidates a path to the nomination, especially if they won early primaries and caucuses—such victories gained these candidates name recognition and increased financial support. Carter took advantage of this change. In his nomination acceptance speech in 1976, Carter proudly mentioned that Democrats had held 30 primaries. He had entered them all. In 1968, Wallace did not have this opportunity. In 2016, Trump did.

The character and extent of Trump’s win in 2024 are the result not only of changes in the political process, but also the changing character of the working class. It is more diverse than in 1968, which explains some of Trump’s gains among African Americans and Latinos. In addition, in the years since 1968, the working class, again least able to afford it, has paid a disproportionate cost for the benefits brought by a globalized economy. Also, the pointy headed theorists and their regulation-writing minions in the federal government have subjected America to a host of edicts that (many believe) defy common sense. Finally, inflation, just emerging as a problem in 1968, has over the past four years harmed the working class most.

All of this reinforces the conclusion that the spirit of Madison Square Garden in 1968 triumphed in 2024. With the possible exception of Reagan Republicans, both parties ignored that spirit. Republicans did not pay attention until Trump seized the nomination in 2016. The Democrats continued to ignore it through the recent election.

A week, the saying goes, is a long time in politics. It turns out that fifty-six years is no time at all.

David Tucker is writing a book on the 1960s and 1970s.

Immensely informative. Thanks.