I’ve seen enough of them in my quarter-century as a college professor. I’ve wasted far too much time arguing with them. And yes, they even exist at Christian colleges. I am talking about the political pied pipers posing as a professors. (Wow–say that five times fast!) They use their classroom and their influence to advance a political agenda on campus and in the classroom. Some of them seem like activists first and teachers of a scholarly discipline second.

Case Western Reserve English professor and former Guggenheim Fellow Michael W. Clune knows the type. Here is a taste of his recent piece at The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Over the past 10 years, I have watched in horror as academe set itself up for the existential crisis that has now arrived. Starting around 2014, many disciplines — including my own, English — changed their mission. Professors began to see the traditional values and methods of their fields — such as the careful weighing of evidence and the commitment to shared standards of reasoned argument — as complicit in histories of oppression. As a result, many professors and fields began to reframe their work as a kind of political activism.

In reading articles and book manuscripts for peer review, or in reviewing files when conducting faculty job searches, I found that nearly every scholar now justifies their work in political terms. This interpretation of a novel or poem, that historical intervention, is valuable because it will contribute to the achievement of progressive political goals. Nor was this change limited to the humanities. Venerable scientific journals — such as Nature — now explicitly endorse political candidates; computer-science and math departments present their work as advancing social justice. Claims in academic arguments are routinely judged in terms of their likely political effects.

The costs of explicitly tying the academic enterprise to partisan politics in a democracy were eminently foreseeable and are now coming into sharp focus. Public opinion of higher education is at an all-time low. The incoming Trump administration plans to use the accreditation process to end the politicization of higher education — and to tax and fine institutions up to “100 percent” of their endowment. I believe these threats are serious because of a simple political calculation of my own: If Trump announced that he was taxing wealthy endowments down to zero, the majority of Americans would stand up and cheer.

This crisis comes at a time in which colleges are ill-equipped to mount a defense. How did this happen?

Let’s take a closer look at why the identification of academic politics with partisan politics is so wrongheaded. I am not interested here in questioning the validity of the political positions staked out by academics over the past decade — on race, immigration, biological sex, Covid, or Donald Trump. Even if one wholeheartedly agrees with every faculty-lounge political opinion, there are still very good reasons to be skeptical about making such opinions the basis of one’s academic work.

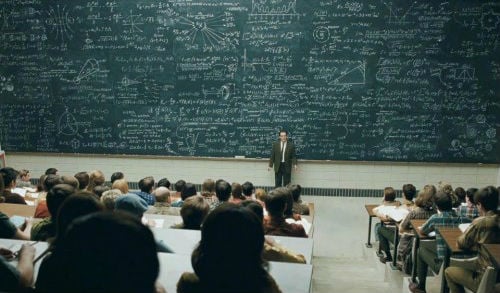

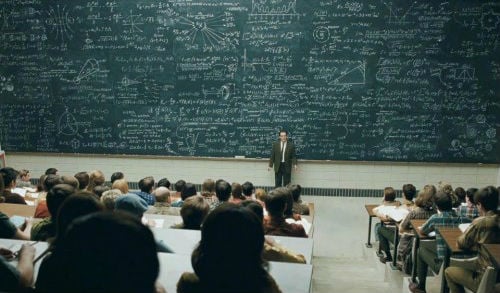

The first is that, while academics have real expertise in their disciplines, we have no special expertise when it comes to political judgment. I am an English professor. I know about the history of literature, the practice of close reading, and the dynamics of literary judgment. No one should treat my opinion on any political matter as more authoritative than that of any other person. The spectacle of English professors pontificating to their captive classroom audiences on the evils of capitalism, the correct way to deal with climate change, or the fascist tendencies of their political opponents is simply an abuse of power.

The second problem with thinking of a professor’s work in explicitly political terms is that professors are terrible at politics. This is especially true of professors at elite colleges. Professors who — like myself — work in institutions that pride themselves on rejecting 70 to 95 percent of their applicants, and whose students overwhelmingly come from the upper reaches of the income spectrum, are simply not in the best position to serve as spokespeople for left-wing egalitarian values.

As someone who was raised in a working-class, immigrant family, academe first appeared to me as a world in which everyone’s views seemed calculated to distinguish themselves from the working class. This is bad enough when those views concern art or esoteric anthropology theories. But when they concern everyday morality and partisan politics, the results are truly perverse. In return for their tuition, students are given the faculty’s high-class political opinions as a form of cultural capital. Thus the public perceives these opinions — on defunding the police, or viewing biological sex as a social construction, or Israel as absolute evil — as markers in a status game. Far from advancing their opinions, professors in fact function to invalidate these views for the majority of Americans who never had the opportunity to attend elite institutions but who are constantly stigmatized for their low-class opinions by the lucky graduates.

Far from representing a powerful avant-garde leading the way to political change, the politicized class of professors is a serious political liability to any party that it supports. The hierarchical structure of academe, and the role it plays in class stratification, clings to every professor’s political pronouncement like a revolting odor. My guess is that the successful Democrats of the future will seek to distance themselves as far as possible from the bespoke jargon and pedantic tone that has constituted the professoriate’s signal contribution to Democratic politics. Nothing would so efficiently invalidate conservative views with working-class Americans than if every elite college professor was replaced by a double who conceived of their work in terms of activism for right-wing ideas. Professors are bad at politics, and politicized professors are bad for their own politics.

Read the rest here.

Several years back, one of my students told me that he and his fellow students had been trying to figure out my personal politics, as I didn’t use my class as a vehicle to try to create converts to a certain ideological position. (I am a registered Independent.) Unfortunately, a lot of other professors at my old employer do not see their classes that way, and all of them are on the left. What I learned in my 30+ years of teaching college economics is that a lot of people (mostly Democrats, but some also on the right) see their classrooms as a mission field that should yield them converts to the teacher’s causes.

Given that the Democratic Party left pretty much controls education at all levels along with most of the media, this situation is not going to change and will intensify in the near future.

There is much of value in this piece, but by focusing on activist classrooms as a unique construction of the left, it strengthens Trump’s argument that somehow the right is above this. The facts, as demonstrated by post Civil War southern history curricula among many other examples, demonstrate a long history of academic activism from conservatives. The very existence of most evangelical schools (not all) further reflects conservative political contestation of the classroom. In my former life as a Christian school history teacher, I was sent by my school to take students to a D.C. student leadership conference run by a huge, international christian school organization. The conference was basically a bootcamp for conservative culture warriors. Speakers included prominent GOP officials who, in between energetic “worship” sessions, urged students to petition their legislators for tax breaks for Christian schools and to fight legal rights for same sex couples. During breaks, stidents went to Congress and sought audiences with their own reprentatives. This does not offset the problems the article seeks to point out, but it is important if the problem is going to be fixed. If Trump does what he has threatened, and this article suggests he could, he won’t depoliticize the classroom at all; he will just silence dissenting voices. The problem is the culture wars, and objectively inclined scholars are threatened by their relentless hunger to politicize everything.

I agree with Earl. What we have now in our elite universities is not good. It should be reformed over time. But replacing it with a right leaning activism is also wrong. This is most likely an oversimplification, but it seems that the left wants to accentuate our sins while the right wants to accentuate our virtues. What is lacking is recognizing our self delusions.

Clune’s article is quite good. I might add that though Clune suggests it was 2014 where things really went south, the trends were clear much earlier. I recall the late twentieth century fuss over Martin Bernal’s “Black Athena,” on the African origins of ancient Greece, which was published by Rutgers University Press, and taken seriously by a lot of people who wanted desperately to believe it, but was clearly pseudo archaeological. Rejection by academics eventually became clear, and we barely hear anything about it now. But there are many recent examples of pseudo scholarship (Kendi and D’Angelo come to mind) that stay popular with the left.