What if the story of the modern world had been told differently?

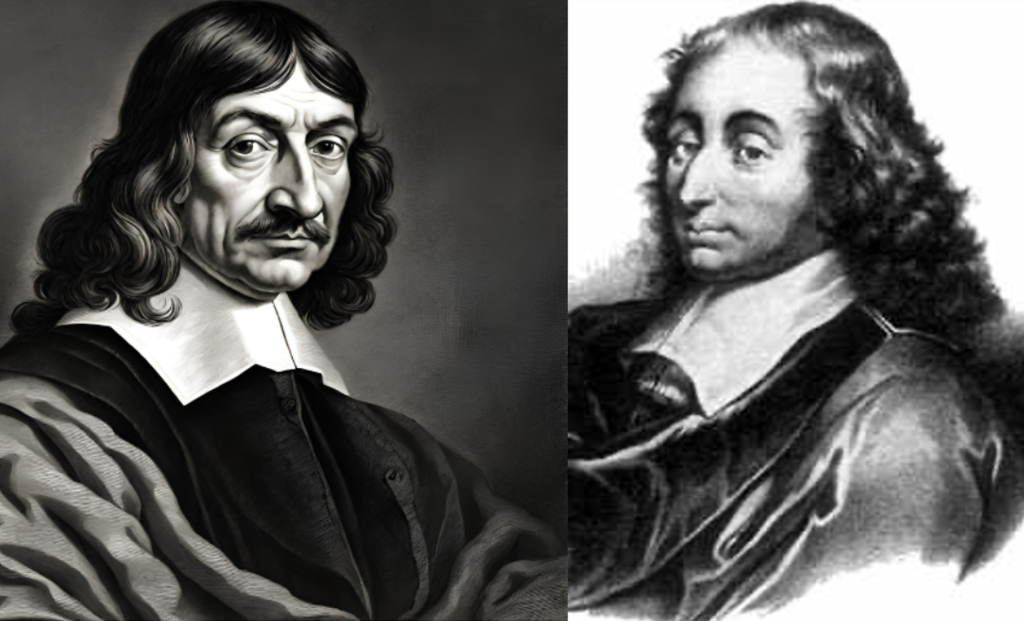

I first encountered Blaise Pascal as a college freshman in the pages of a western civilization textbook and was intrigued by what I found. Pascal clearly did not fit the stereotypical picture of the emerging “modern,” moving inexorably in the direction of “progress,” freed from the tyranny of arbitrary political and religious authority, and confident of human potential empowered by reason, science, and technology. Pascal did not share that unclouded optimism.

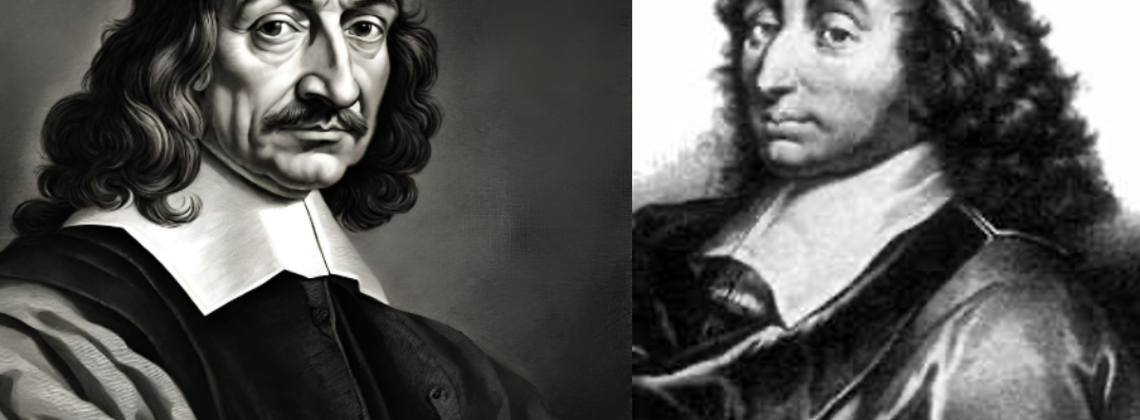

During my graduate school studies in modern European history, Pascal did not feature as a major character in the standard narrative of the Enlightenment—and not even in the more focused area of intellectual history. Instead, it was Descartes who always seemed to be given credit for daring to pursue an understanding of the human condition unclouded by the presuppositions of revealed religion. Even though Descartes remained a member of the Roman Catholic church, his pursuit of truth outlined in his 1637 publication Discourse on Method sought to free the pursuit of reliable knowledge from its traditional ties to revealed religion.

First he abandoned any philosophical or theological presuppositions. Then he identified his most unshakeable conviction: his capacity to doubt. From there he moved in a deductive step-by-step process, accepting only “clear and distinct ideas” and ending up with a framework that asserted our ability to trust our sense perceptions of the external world. A divine being figures as a critical step in the argument as the one who guarantees that we are not deceived as the data from the outside world makes impressions on our inner life of the mind. While Descartes’ mention of divinity may have allowed him to escape the charge of atheism or heresy, his god was most certainly not the personal and trinitarian God of Christian orthodoxy. Perhaps most significant of all, Descartes’ account identified rationality as the most quintessential feature of humanness. His dictum, “I think; therefore I am” says it all.

Early in my intellectual journey, I bought a copy of Pascal’s Pensées. The well-annotated pages and their tattered corners testify to my engagement with Pascal over the past four decades. I appreciated his enduring understanding of the complexity of the human condition and the wide range of topics addressed. Most of all, I treasured his willingness to struggle with the tensions posed when we allow the claims of reason, science, and faith to speak to each other. He would rather remain true to the complexities of his faith and doubts than abandon part of himself for the sake of inner calmness or intellectual consistency.

What I failed to do during those years was to see Pascal in his historical context or to delve into the secondary literature surrounding Pascal. I unwittingly fell into the pattern of the standard narrative, treating him in isolation and as a marginal figure in the narrative of modernity. I saw him as a kindred spirit and fellow human being but without serious relationship to our historical context.

That is until this past spring when, on a book table at a Baylor University conference, I saw Wagering on an Ironic God: Pascal on Faith and Philosophy by Thomas Hibbs. This inspired me to pick up Peter Kreeft’s Christianity for Modern Pagans: Pascal’s Pensees Edited, Outlined and Explained and the more recent book by Antoine Compagnon, A Summer with Pascal. Together, these books served to place Pascal in the context of the classic questions of philosophy going back to Socrates, to set him in the framework of the culture of his native France, and to enhance his relevance as a spokesperson for the Christian faith in the context of the twenty-first century.

Since reading those books, I have been returning to a fantastical counter-factual thought experiment. What if Pascal rather than Descartes had been taken as the founder of the modern Western intellectual world? I have been reflecting on how the world and our lives might have been different. Consider the following possibilities.

Instead of picturing humans as, most essentially, rational beings, we would be thinking about humans as complex beings influenced at any moment by the interplay of reason, desire, religious sensibilities, sense experience, emotional attachments, intuitions, imagination, and historical context. We would be less likely to assume automatically that emotions are a hindrance to clear thinking or that reason is inherently the most trustworthy guide to a complete understanding of a situation. (This point has new relevance in the context of AI. It would be harder to distinguish a Cartesian human being from a robot than a Pascalian human being!)

Instead of assuming that everything important to our understanding of the world has the clarity of logical syllogisms or mathematical equations, we would appreciate the importance of leaving space for mystery and wonder.

Instead of assuming that our only hurdle to making the world a better place for human beings is to know the good, we would also appreciate the role of the will and of desire. It is not enough to know the good, or to have the truth. Having knowledge is only the first step. We must choose to put it to work in partnership with wisdom.

Instead of thinking of God as a convenient step in building a valid argument, or as the conclusion of a logical argument, we would think of God as a person who desires not just belief in his existence but desire for his existence, who intentionally “hides” in the world to make space for our freedom, and who showed us the model of love by choosing to bear the weight of the human condition even to the point of suffering.

It is too late to change the dominant narrative about the modern period. Descartes will retain his prime place in the story. But in this moment of cultural crisis—when the modern confidence in an upward trajectory of human progress seems ever more in doubt; when the powerful tools of reason and science seem so limited in addressing our most vexing human challenges at every turn; when the very tools of technology threaten to become our masters rather than our servants—perhaps we can take comfort in knowing that Descartes is not the only seventeenth century thinker who dared to reckon with the challenges of the human condition in that turbulent season of changing political, intellectual, and social assumptions in so many ways just like our own.

We can reclaim Pascal for our own journeys and, like Pascal, refuse to take a reductionist view of the human condition. We know we are not just autonomous, individualistic, reasoning beings. We need community, relationships, and love. Like Pascal, we can decide not to make our questions smaller just because we do not have ready answers. Like Pascal, we can choose to embrace the mystery and complexity—even the strangeness—of the world in which we find ourselves. And perhaps, just perhaps, we will, like Pascal, during his famous “night of fire,” encounter unexpected joy and hope that we could neither have anticipated nor imagined.

Shirley A. Mullen (PhD) is President Emerita of Houghton College and longtime history professor. Her most recent book is Claiming the Courageous Middle: Daring to Live and Work Together for a More Hopeful Future (2024).

As someone who thinks that mind/body dualism has caused a lot of our worst modern problems, I loved this thought experiment so much! Thank you.