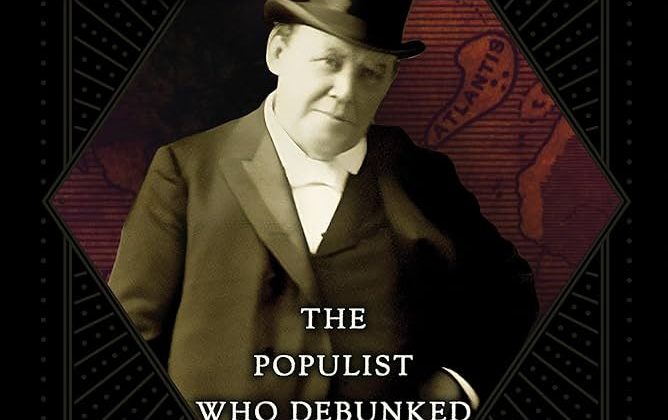

Zachary Michael Jack is Professor of English at North Central College. This interview is based on his new book, The Strange Genius of Ignatius Donnelly: The Populist Who Debunked Shakespeare and Found Atlantis (Northern Illinois University Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write The Strange Genius of Ignatius Donnelly?

ZJ: A generous colleague who knows my work sent an email with a kernel of an enticing idea and some heartfelt encouragement: to write a sort of intellectual biography of Ignatius Donnelly, one focusing on the potential overlap between his political views as a pro-reform populist politician, and his many pathmaking philosophical/ideological novels, some of which achieved what amounts to bestseller status for their era. As someone who both studies political history, and writes contemporary fiction and narrative nonfiction, I felt a special kinship with Donnelly’s predilection for writing in multiple genres.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of The Strange Genius of Ignatius Donnelly?

ZJ: At root, the argument of the book is that Donnelly is an important, and badly overlooked, figure in Gilded Age America. But to be more specific, I’d say The Strange Genius of Ignatius Donnelly is an argument for personal reinvention, since its subject was a man who reinvented himself in middle age, transforming himself from former politician into celebrated “sage,” public intellectual par excellence, popular author, and so-called Father of American Populism.

JF: Why do we need to read The Strange Genius of Ignatius Donnelly?

ZJ: History, as taught in American classrooms, leaves out so many noteworthy and influential individuals. By rights, Donnelly’s personality and philosophy should make him nearly as canonical a figure as, for example, William Jennings Bryan. Yet his conspicuous absence from standard American history textbooks illustrates our tendency to overlook those who march to a different drummer, or whose professional or political allegiances are less rigid and more mercurial. At one time or another, Donnelly belonged to at least six different political parties. So while many of his colleagues stayed stuck in a professional or ideological rut, he kept learning, growing, and changing.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

ZJ: I’m not sure exactly when a historical writer crosses over into being an actual “historian” in practice, and in terms of professional identity. But I think growing up on a multi-generational family farm probably hard-wired me for receptivity, to the extent that I learned to view my people and my place in a light of a larger cultural and familial context. History’s layers were palpable to us. Every time any one of us set about painting the old barn or digging in the dirt we found compelling evidence of those that had traveled similar paths before us.

JF: Tell us about the kinds of sources that you used to research for this project.

ZJ: The project involved hundreds of primary and secondary sources in total, the most colorful of which were probably the columns Ignatius Donnelly penned for newspapers in his home state of Minnesota. Always provocative and occasionally combative, Donnelly was at his rhetorical best in defense of the marginalized, the overlooked, and the wrongfully dismissed.

JF: Thanks, Zachary!