Vinson Cunningham’s novel tells of more than a mortal God

Great Expectations by Vinson Cunningham. Hogarth, 2024. 272 pp., $28.00

The first time David Hammond hears the unnamed Senator from Illinois speak, he recognizes a “black pulpit touch” that leaves him “almost flattered” by the feeling of “being pandered to so directly by someone who so nakedly wanted something in return.” In retrospect David sees that even then, long before he started to work on the Senator’s campaign, the politician of hope had courted the faith of true believers—had conceived of his supporters as “congregants, as members of a mystical body, their bonds invisible but real.”

Though New Yorker critic Vinson Cunningham’s debut novel Great Expectations is set in a land that separates church and state, the narrator is all ears for political inflections that are inescapably religious until the end. At a Los Angeles fundraiser, David the campaign-aid is startled to find a Pentecostal pastor who—though he previously dismissed politics as “distraction from the work of holiness”—has paid no small fee to see the Senator in person. “Something is shifting, son,” the pastor explains, seeing “a move of God in the campaign that [can’t] be explained in purely political terms.”

But the Candidate’s treatment of David as a dispensable functionary leaves him incapable of believing the pastor’s assurance that, as president, this mere mortal man will “usher in some new, unimaginable dispensation.” Instead, as the Candidate claims his victory in the final pages and David’s colleagues explode with exuberance, he sees the Senator—suddenly President—as a “moving statue, made to stand in a great square and eke out noise,” a cipher “I couldn’t admire.” David cannot clap with the crowd but only pulls out his phone, and we leave him as he “stretched [his] arm unprayerfully toward the stage and took a picture.”

While some readers and reviewers have exulted nostalgically in the novel’s purported re-creation of the hope-and-change days of the Obama era (Cunningham worked as a staffer on the former president’s campaign), to do so is to misread the book, which is so clearly a sentimental education that leads David from self-deceit to lost illusions.

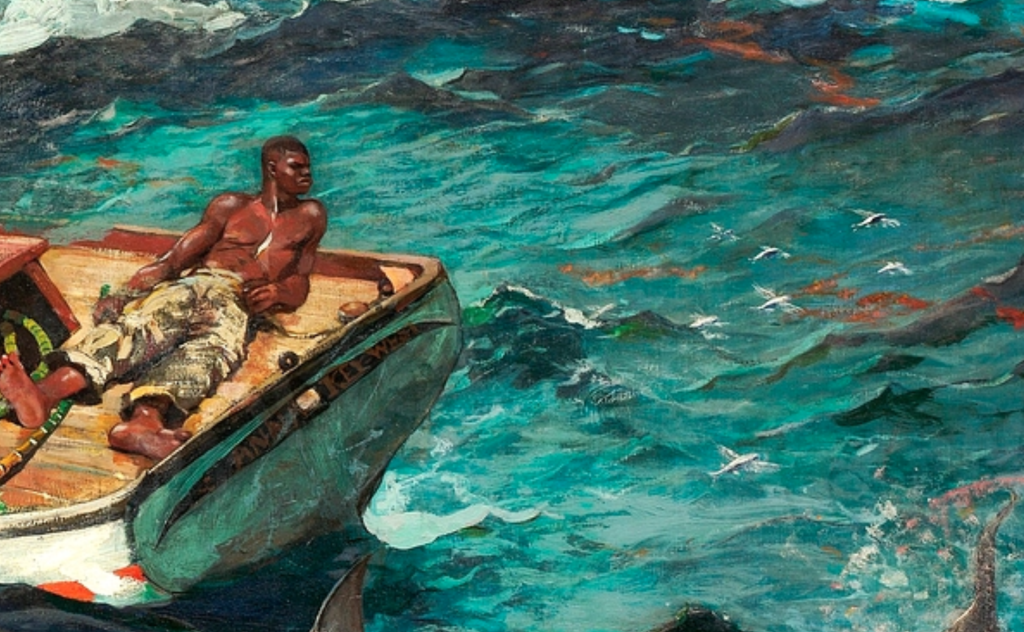

But before this conclusion, like the White Whale of Melville’s Moby-Dick, the Candidate becomes a blank screen for competing and contradictory projections, a malleable symbol endowed with numinous powers to conjure eschatological change. It is no accident that the novel’s paperback cover bears a resemblance to the frontispiece of Hobbes’ Leviathan. Does the single sovereign “stand for” the interests of many, or does the democratically elected ruler subsume the diverse demands of the demos until they disappear in his own libidinal will to power?

Caught up in the corruptions that complicate the campaign of hope, Great Expectations is comprised of David’s ruminations. During childhood, he “used to read the Bible on anxious nights,” searching for a fullness on the other side of this present darkness, through which “we know in part, and we prophesy in part.” By the time he joins the Candidate’s campaign, David has passed through several “stages of belief and unbelief,” though when a fellow staffer presses him with “You’re like, into church, huh?” he confesses “In a certain way, yeah.”

The substance of David’s spiritual questing is tested when he sleeps with Regina, another staffer who wakes him up the morning after to declare, somewhat sheepishly, “I’m getting baptized.” On either side of orthodox Christianity, contemporary trends in spirituality and religion tend in two directions. On the one hand, we witness a demand for the divine divorced from doctrine. As Joseph Ratzinger argues, whereas orthodoxy can marry the mystical and the dogmatic, in the increasingly attractive “completely antirationalist pattern of religion” the absolute takes the form, in “modern ‘mysticism,’” of “not something to be believed in, but something to be experienced.” David is drawn at times to this mode, though he is drawn to a deeper, more metaphysical spiritual vision bestowed by one of his Catholic school teachers, who through the poetry of Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins left an unshakeable impression that “The world is charged with the grandeur of God / It will flame out, like shining from shook foil”—an embodiment of what the teacher called “a sacramental view of life,” by which “not only the wine and the host but trees and sunrises, sea and sand could act as a kind of portal into the action of the Trinity.”

On the other hand, searchers like Regina settle for a demystified gospel fit for secularized activists. “Pastor Bill,” the man who brought her to baptism, “talks about a God I can sort of understand . . . he talks about action: politics, looking out for the poor.” Commitment to the poor is at the core of Christianity, but the motivation and spirit of that care comes from Jesus’ insistence that “whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” Regina’s pastor promises that “I’ve ‘given my life’ for something ‘bigger than myself’ . . . and that this makes me like a miniature Christ.” She need not assent to “the idea of some invisible Person watching over me.” The pastor gives her a dispensation from faith in the real (rather than symbolic) resurrection, reducing religion to a self-actualizing cause stripped of ascetic sacrifice and spiritual conversion: “He says God’s the stuff I already care about, the people I already love. Which, to me, makes sense.”

Although David keeps sleeping with her, this flattened God does not make sense to David, who cannot shed the yearning to marry the seen and the unseen, body and soul. Since he was a young man, David found solace in the Song of Songs, precisely because “the book isn’t just some blank description of Eros.” In his reading, the biblical book grants that sex is “animal instinct, something to enjoy and exult in and herald with song in its own right and for its own purposes,” but it is also—and this, for him, is perhaps more pressing—“a metaphor forever intensifying love between the human and the divine, the created and the Creator.” The catch? When David joined his “pinings after girls and spiritual depth” and started sleeping around, he found the connection between body and spirit “fraying.” Because he cannot extricate eros from the Song of Songs, David demands that the marital act with any woman deliver profound “discovery.”

Predictably, when he confides his wrestlings to Regina, she insists he’s got it all wrong—that spontaneity and technique, innocence and experience, can meld in way that “allows you to guide and be guided at the same time”—an innovative and individualistic approach that sheds scriptural precedent, because “it wouldn’t be so good if you could do it under the influence of some, like, literature.” Also predictably, the novel renders campaign fraudulence as a black-and-white evil, whereas sexual transgressions are treated with a far more indulgent touch—an ethical hierarchy that fits cozily into our permissive age.

Yet by the end of the novel, David’s experimental exegesis of Song of Songs is replaced by the Deus absconditus of Isaiah (45:15). When the rest of the staffers gather, giddy, at the aforementioned victory party, David first takes a detour to an old Catholic church of his childhood, St. Benedict’s. There he realizes, “I couldn’t remember a single thing about the black saint after whom this church was named.” He seems to be referring to St. Benedict the Moor. Tangling Benedict and a trader named Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, the latter becomes “the holy figure through which I directed my prayer—a sudden prayer had started; this, I realized, was why I’d left the hotel—to God.” He leaves the church with lost illusions and a longing for the “veiled God” of his youth, whom he couldn’t quite understand, unlike Regina who has chosen to follow a God she understands well.

As Cunningham observes in an interview, the novel as a form is defined by contingency and hesitation that can be traced directly back to the essays of Montaigne, for whom—says Pierre Manent in Montaigne: Life Without Law—“the human mind spontaneously, naturally, necessarily wants to engrave where there are only fleeting lines, uncertain forms, and unforeseeable metamorphoses.” In the face of competing questions and claims, the mood of the novel, as a form, is a constant maybe. But there are degrees of doubt and uncertainty, and sometimes maybe is a rationalization of moral indecision, a kind of cowardice justified by professional skepticism.

What if that experience of mystical unknowing does move David’s hand when, in the last line, he lifts up his arm “unprayerfully?” Coming on the heels of his visit to St. Benedict’s, we see David leave those same arms open to a God who is more than the sovereign political ruler as defined by Hobbes and more than the mortal god who is, through David’s last gesture, dead.

Joshua Hren is founder and editor of Wiseblood Books and co-founder of the MFA program at the University of St. Thomas. He is the author of ten books, including the theological-aesthetical manifesto Contemplative Realism and the novel Blue Walls Falling Down.