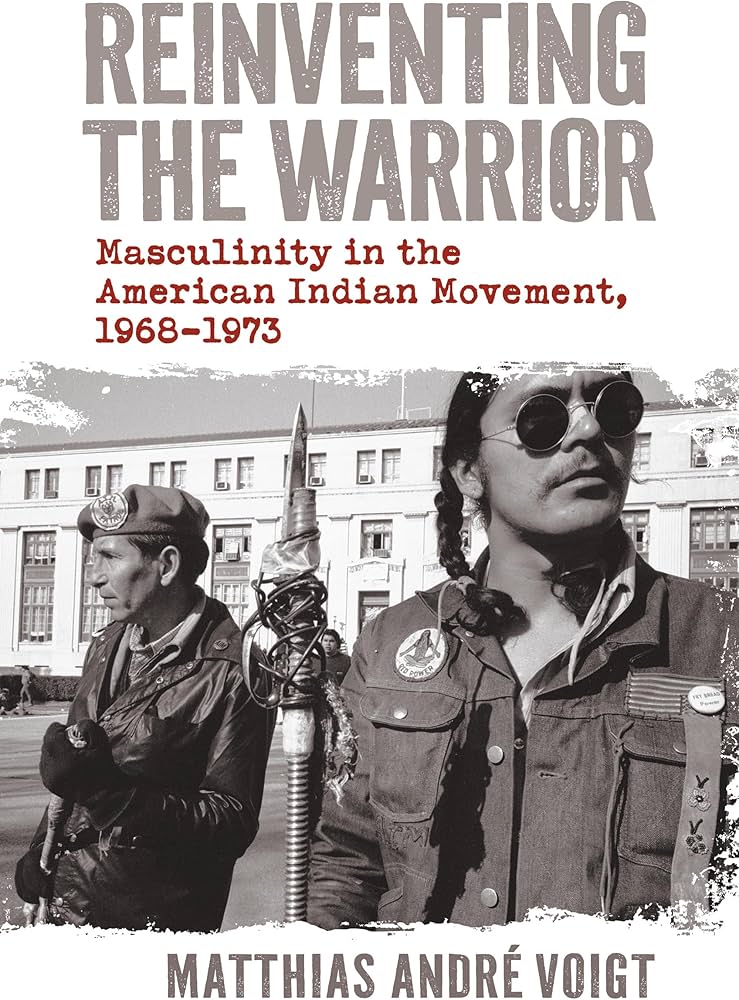

Matthias André Voigt is Part-Time Lecturer in Modern American History at Free University Berlin. This interview is based on his new book, Reinventing the Warrior: Masculinity in the American Indian Movement, 1968-1973 (University Press of Kansas, 2024).

JF: What led you to write Reinventing the Warrior?

MV: During my master‘s degree, I became interested in 1960s and 1970s social and protest movements. When doing research on “Black Power“ activism, I came across the term “Red Power“ and became fascinated by Native activism. Native activism arrived on the heels of various ethnic, social, and gender protests. And an inside view and gendered perspective on one its key organizations and its activism –the American Indian Movement– was largely missing.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Reinventing the Warrior?

MV: In the book, I make the argument that during the 1960s and 1970s Native men reinvented themselves as warriors in efforts to maintain their cultural integrity and demand the upholding of their political rights. Just as their ancestors before them, these Native men, too, considered themselves warriors in a struggle against the latest devastating policies of settler colonialism in defense of their homeland, their rights, and their people. The book explores the ways in which Native men and masculinities reinvented themselves as men and as warriors in complex processes of nation-building.

JF: Why do we need to read Reinventing the Warrior?

MV: The book examines why and how Native men in the American Indian Movement reinvented themselves as men and as warriors between 1968 and 1973, remaking self and society in the process.

First, the book seeks to make new sense of the American Indian Movement and the social dynamics of this far-reaching social movement for change. This book explores why and how participating in “Red Power“ activism provided an avenue for Native men to overcome feelings of disempowerment, emasculation, and cultural disconnect. Native men reinvented their identities by protesting those conditions that kept them oppressed and by turning toward their own cultural traditions, renewing, revitalizing, andremasculinizing. I argue that the increasingly confrontational struggle for Native rights –initially in urban areas, then in border towns and on reservations– transformed Native subjectivities, producing new expressions of Indigeneity in the process.

Second, the book sheds new light on the gendered dimensions of nation-building. Scholars have long established the close linkage between gender and nationalism. What has been less well-established, though, is the link between nationalism and masculinities, in particular the role of marginalized masculinities within these processes. Reinventing the Warrior calls attention to the ways in which Native men engaged in gendered nation-building processes, fundamentally altering what it means to be Native and transforming settler-colonial-Indigenous relations.

The book follows a paradigm shift in describing and analyzing Native history through Indigenous perspectives and voices. It is the first major work utilizing Indigenous Masculinity studies within the context of the United States. It offers fresh insights into the interrelationship between masculinity and nationalism.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

MV: During my master‘s studies, I became immersed in U.S. contemporary history, with a strong focus on social and ethnic history. Later on, I specialized in 20th century Native American history. In 2013 and 2019, I spent considerable time in the urban Indigenous community of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis/St. Paul and on reservations in South Dakota (Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Cheyenne River, Standing Rock). Experiencing Native realities on the ground has fundamentally helped me to gain a deeper unterstanding of Native people, their culture, and their daily struggles.

JF: What is your next project?

MV: For my next project, I would like to focus on the experiences of Native war veterans. Their cultural motivations for military service, their experiences in “the white man‘s army“, their homecoming, and their connection to cultural traditions have remained largely warranting further research. And I am looking forward to (re)visiting reservations and listening to their oral histories.

JF: Thanks, Matthias!