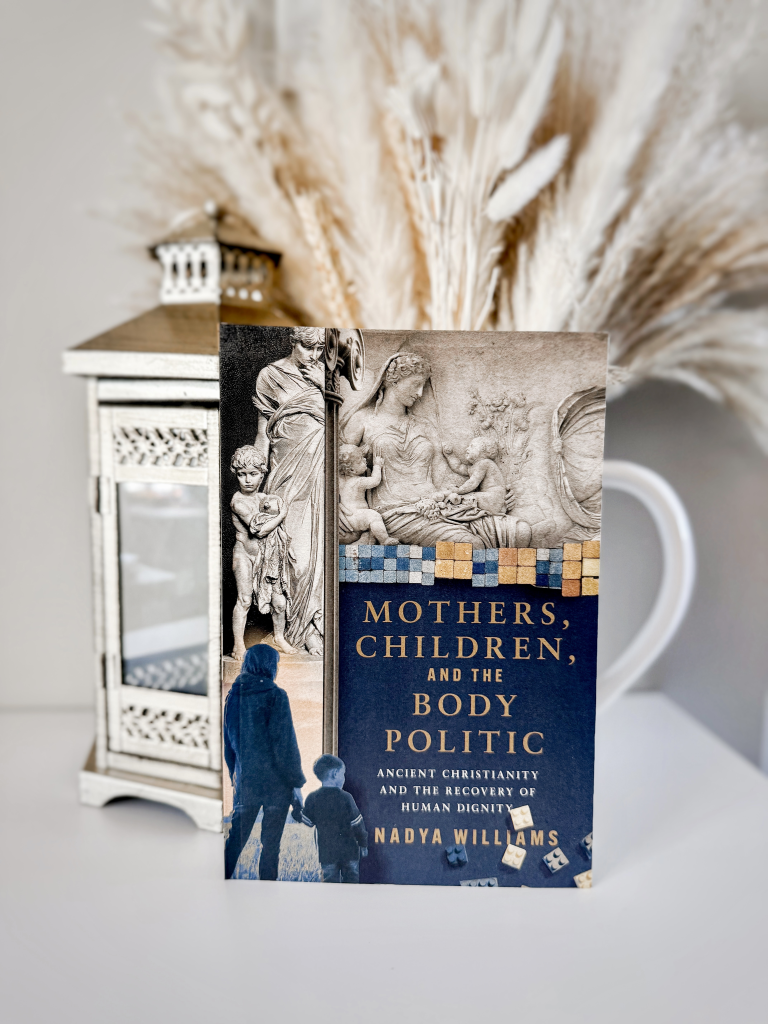

Today is book launch day for Arena editor (and Current managing editor) Nadya Williams: Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic: Ancient Christianity and the Recovery of Human Dignity is out today from IVP Academic! I (Dixie) wanted to ask Nadya a few questions about the origins of the book and about some of its most intriguing arguments, so I wrangled permission to share an interview here with the author herself. Enjoy—and Happy Book Birthday, Nadya!

****

Your first book, Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan, 2023), examined how early Christians both radically challenged Greco-Roman culture and struggled with their attachment to pagan lifestyles and ways of thinking. Your new book includes a great deal of historical analysis but also closely examines the way that present-day American culture devalues human life (and mothers and children, in particular). What led you to write about this particular topic?

It is funny to see these connections between the two books! In both, I am fascinated by how our cultural setting affects our assumptions—how we think about fundamental concepts in life, but perhaps don’t even realize that the way we think and behave is entirely because we’re copying the default mode around. For Christians, this should be particularly alarming or at least convicting, because Christians have always claimed to be counter-cultural—and the claims of Christianity certainly are!—but we also live in our particular circumstances.

In the case of this book, the idea came to me just a couple of months after I had turned in the complete manuscript for the Cultural Christians book. I wasn’t looking to jump right into a new project, but then I saw yet another one of those infuriating stories, in a major national news outlet, claiming that mothers are much more miserable than women who never have children. So, I sat down to write what I thought would be a short essay in response.

I wasn’t interested in disproving the piece—many others have done so quite ably, especially Brad Wilcox, who has been gathering data about the happiness of married people and parents for well over a decade now! But what I realized I could contribute to the conversation was historical and cultural analysis: What does it say about our society that people (including journalists and public analysists and other writers) keep talking in such disparaging ways about motherhood and about children? And what does it say about the church, if so many Christians are deferring marriage or privileging career over family? Finally, what might voices of life sound like in our culture that wishes some people didn’t exist—and offers abortion to make this wish come true in some cases?

One of your strengths a writer is your ability to connect ancient stories with modern concerns in an almost seamless manner. As I learned more about Greco-Roman assumptions about women, children, and other low-status people, I began to grasp that the presumption of universal human dignity—which I might previously have considered a matter of common sense—is actually peculiarly Christian. What do you think is the most important difference between how ancient peoples viewed women and children and how Christians do (or at least should)?

Thank you for this question—it is indeed one of the key arguments in this book. On the one hand, as I just noted, many of our assumptions about life today are warped by contemporary culture. But on the flip side, there is, I realized, immense good that has come to our culture because of two millennia of Christianity. These two millennia are, as I wrote a few months ago in Christianity Today, “How We Learned to Hate Genocide.”

In antiquity, we see leaders as Julius Caesar view all people as divided into two essential categories: those who could be abused or killed, and those who could not. This meant that some people were simply not seen as quite fully human.

By contrast, Christianity holds as axiom that all people are unconditionally priceless in God’s eyes. Yes, we think of this pro-life proclamation as something that involves opposing abortion—but this view is unnecessarily restrictive and myopic when thinking about what it means to be pro-life and pro human flourishing. So we see in the early churches a mixing of wealthy and poor, slave and free, men and women, in ways that were unfathomable in traditional Roman society. This includes the likewise revolutionary idea that single women (including women who chose to not get married) are also treasured daughters of God—a concept no less contentious in the first or the third century AD than today.

In the first chapters of the book, in particular, you repeatedly use the term “image bearer” not just to explain that all human beings are made in the image and likeness of God, but as a synonym for “person.” Tell us more about this choice and what changes when we replace the word “child,” for example, with “image bearer.”

So much of the callous language I’ve noted in the media discussions about mothers, children, the elderly, the disabled—really, any categories of the vulnerable—stems from coldly detached calculations of cost and convenience. This view sees some people as a “cost” to society—imagine, for instance, someone with a disability. Such a person requires a lot of resources but would never be able to provide goods or services sufficient to balance it out or pay off the debt, if you will. When looking at this person through a purely utilitarian lens, it is easy to say: Why does our society need someone so useless, someone who is just a drain on resources that could be better used on someone else?

But looking at people as image bearers of God, we can make the argument—as Amy Julia Becker has done, for instance—that “we need useless people.” God doesn’t see any of us as useless. We are image bearers, and therefore, our worth is priceless in God’s eyes and is not conditional on any set of qualifications or circumstances. This is a truth as revolutionary and beautiful today as it was two-thousand years ago. But the move of our society into a post-Christian direction is eroding this fundamental belief.

You have now published two books in as many years and are in the midst of the editing process for a third! What can you tell us about this upcoming book? What is next for you as a historian, author, and editor?

Yes! I just submitted my edits for Christians Reading Pagans, so it’s off to copyediting. Readers can look for it from Zondervan Academic in 2025. It is a survey of Greco-Roman literature from Homer to Boethius, governed by this question: How might Christians today read the classics of Greco-Roman literature as Christians for spiritual formation? I hope that this book will appeal to a fairly diverse audience: students and teachers in Classical Christian schools; Great Books classes in Christian colleges; Christians who are interested in reading the books that many of the earliest converts to Christianity read and knew.

So often people ask me: What should I read to understand the early church (and early Christians) better? And my answer is: Homer! And Vergil! And other Greek and Roman authors. This book aims to equip Christians to do this kind of reading well.

As for what’s next: I’m in the beginning stages of a book that considers what I term the “pink scandal of the evangelical mind.” I test-drove some ideas for this project in Christianity Today last year. I want to encourage women in the pews to live the rich intellectual lives that Christ has called us all to live! As is the case with everything I write, this book also will combine ancient history with theology—but will (hopefully) bring this all to land in our very modern lives.

I’m also very excited as an editor to continue working on Current under the able leadership of Eric Miller, Jay Green, and John Fea. It’s been exciting to see this magazine grow and thrive. 2024 only highlights further just how important our work is in the present climate—intellectual, political, cultural. If you’re not reading us regularly already, I invite you to join now!