About a year ago, a new wave of Shakespeare skepticism was stirred up. Richard Hanania, political commentator, suggested: “Pretty sure if you gave me a year I could write Shakespeare quality work. Like if someone hadn’t read all of Shakespeare and you randomly gave them me or him, on average they couldn’t tell the difference. Of course without the blind test people would pretend it wasn’t as good.” A lot of bros have agreed with that in the past year, or at least have doubted that Shakespeare is all that good. Maybe he just got there first. That is the opinion of Sam Bankman-Fried and some others.

Why stop there? Not longer after Hanania’s quote, “tech bros” began to publicly argue that books, as a whole, are overrated. They take a lot of time. Why can’t a summary suffice? Or a podcast on 2x speed? As some of these people are sometimes considered the smartest in the room, their talking points have trickled down to normal, everyday X users, and podcast listeners, and high school students. I have heard a college student say that Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream “is mid” and “Shakespeare isn’t even that good.” Has he read all of Shakespeare? Of course not. But he knows.

Skepticism about books or culture is hardly new or different or exciting. Anti-intellectualism is a grand American tradition. (See Richard Hofstadter.) It does cause some additional concern when we consider how little young people are reading in schools these days. The Atlantic recently published a piece about “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books.” It is not that they are illiterate, it is that many of them have never been assigned a full book before. It has been all excerpts, and now it is hard to meet college expectations.

Of course, comments about Shakespeare being overrated are also evidence of why education exists and must continue to exist. One of the purposes of education is to get us to the point Socrates begins and ends many dialogues at: we do not know as much as we think we know. We may know next to nothing. If education teaches us nothing more than to curb our hubris, it will have taught us a great deal. It may be something of a shock to the system of some youth that people have not been reading Shakespeare for the past five hundred years or so only because we had not yet learned of his flaws from Gen Z. One of the best things about the subject of history is how it can remind us that we too often overestimate ourselves and underestimate the people of the past.

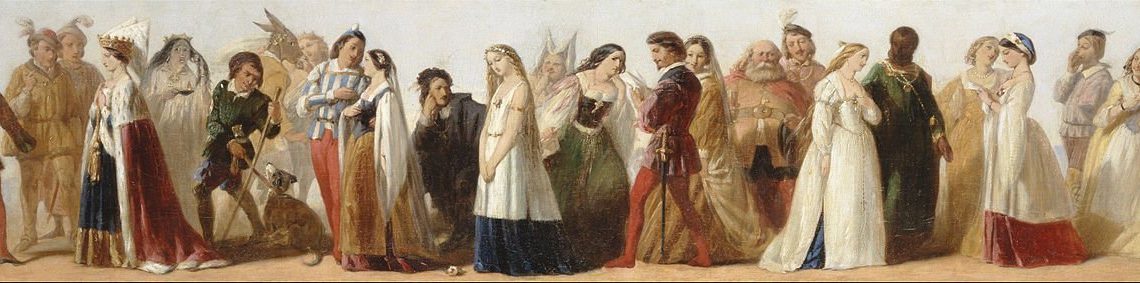

Even if one is a complete skeptic about the canon (and Shakespeare), education can show us how these works can open our eyes wider to the wonder and interconnectedness around us. Perhaps Shakespeare is not your favorite poet or playwright. No matter. Once you learn a bit of his work, you will begin to better understand many other works by many other artists. You may even see The Lion King in a new light. Maybe you do not care at all for The Odyssey or The Aeneid. Knowing them will still initiate you into a “great conversation” that has been happening for centuries. You can participate in that conversation once you are familiar with some of its key texts. You can engage with the minds and works of a constellation of thinkers. This is worth reading a few works you might consider “mid.”

If you come to embrace “the classics,” you will find new pleasures opened to you. You can be excited about things you can get from the library for free. You can have a conversation with anyone who has done some common reading, regardless of what you do or do not have in common personally. You can also understand and appreciate some recent news. Right now, there is a great deal of excitement about some new works, by Mozart and G.K. Chesterton. A recently re-discovered early Mozart piece was performed. It was previously unknown to us and has all kinds of people intrigued. A “new” G.K. Chesterton essay was also found and the prospect of reading it has set some hearts aglow.

Even if you read all the “classics” and never warm to them, even if you only look at people like Milton through rolled eyes or envy, the canon has something else to offer you: memento mori. Many people love to hate Descartes, but we are reading him hundreds of years later. How many of us will pen one hundred words that will be read in five years, much less five hundred? Like it or not, Ars longa, vita brevis. You may think you have more and better things to say than Ovid, but Ovid’s work will outlive you. And if you want to be remembered, you had best get busy doing something, not just saying something. Not respecting Shakespeare will not get you very far in contributing to that great conversation.