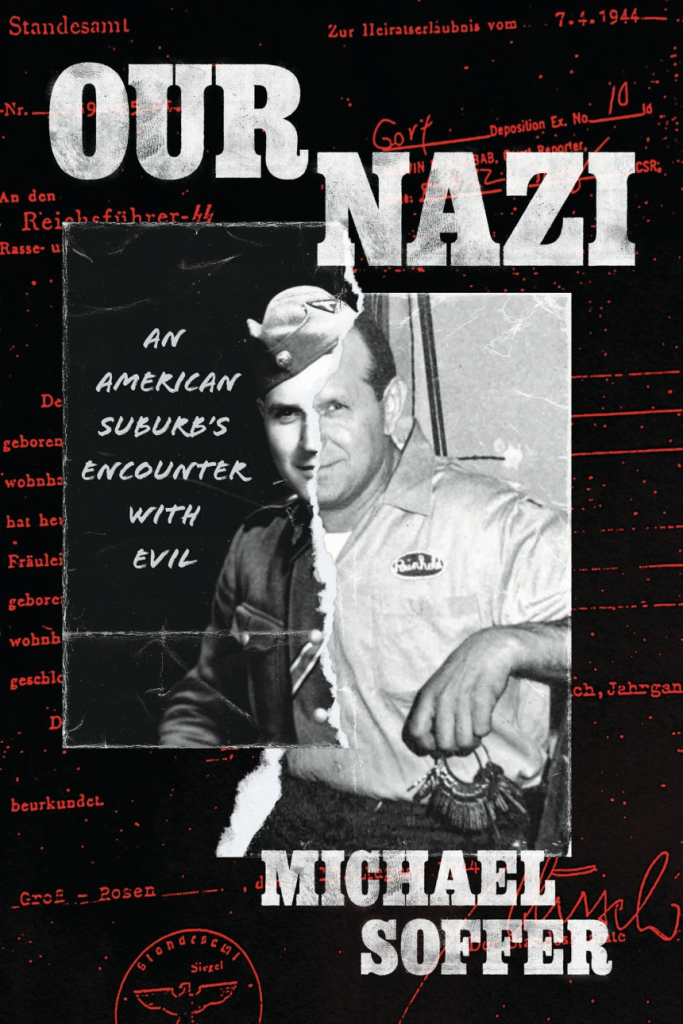

Today is book launch day for Michael Soffer, the author of Our Nazi: An American Suburb’s Encounter with Evil (University of Chicago Press). We are delighted that Michael took the time to respond to a few questions about his research and the fascinating story behind this book, and we look forward to publishing a review of the book this winter.

***

Could you tell a little bit of your journey into this book? How did you come across this topic, and at what point did you decide that there was a book here and that you were the one called to write it?

This book grew out of my classroom. In the fall of 2020, in response to a wave of antisemitic hate crimes at Oak Park & River Forest High School, I began teaching a Holocaust Studies course. To make the curriculum more personal, I embedded the stories of two Jewish families from Poland throughout the course, and we would end class each day by looking at how those families experienced the events we had studied. Having grown up in River Forest and attended OPRF, I knew that a former camp guard had later worked at the high school, and so I worked his life story into the curriculum as well, as a sort of contrasting throughline, but I did not tell my students who any of these individuals were, or why I had chosen their stories.

As the semester went on, the students learned that the Jewish families were actually my wife’s grandparents, and the Nazi had worked at their school for two decades. I hoped they would see that the legacy of the Holocaust was not so distant. My students–this brilliant, curious group of kids–became fascinated by Kulle, and particularly by how our town had rallied to his defense. They asked if we could somehow bring people who lived through that moment to guest speak in class. We began searching through digitized articles from the local newspapers for names of folks who had been involved, and I started making calls and sending emails to see if anyone would jump on Zoom to talk to the kids.

One night, a former school board member told me that when the board asked Kulle if he had ever committed murder, Kulle answered, “I don’t remember.” When they asked if he had any regrets, Kulle said, “I just wish we had won the war.” I had barely finished recapping the call to my wife when she said, more as a statement than a question, “So you’re going to write a book?” It took me a little longer to admit to myself that I was starting a book project, but I was immediately obsessed with this history, and it felt deeply personal.

I was teaching Holocaust Studies in a classroom that a former Nazi camp guard used to clean, and in a building that had rallied to his defense. Having grown up in the community and taught at the school, I had a unique access point to this story and its participants. Still, the idea of writing a book–let alone getting it published–seemed daunting and unrealistic. But the first time I spoke with Rima Lunin Schultz and RaeLynne Toperoff, the two women who led the push to have Kulle removed from the high school, I knew I had to try. They had experienced so much pain and hurt, and the world needed to know their story.

The joke about historians is that we complicate everything. To this accusation I usually retort that the sources do that complicating for us quite nicely without our aid. We just have to listen to them. Was there anything in your research that was particularly surprising or unexpected? Was there anything that complicated the picture that perhaps you had of the topic before digging deeper?

I love your reply! Today, “Nazi hunters” occupy an almost mythical presence in our collective consciousness, but the efforts to bring Hitler’s men to justice faced significant opposition.

I at first set out to explore that opposition, to understand why so many Americans rose to defend the Nazi war criminals uncovered in their midst. I had not anticipated just how visceral and impassioned that opposition was, especially in my hometown–a place with a national reputation for its commitment to diversity and integration. In Oak Park, and in other communities across the country, a consistent pattern emerged. First, friends and neighbors denied the allegations; then, they downplayed them. Finally, they argued that forgiveness was the more moral response.

The Kulle case was particularly jarring because it was Oak Park. Some of the same people who had worked to integrate the suburb, and had shouted down a neo-Nazi rally in 1980, soon supported an actual Nazi camp guard. What made the case even more striking was that Kulle was so brazenly guilty. He volunteered for the SS. He spent more than two years at a slave labor camp. He was promoted multiple times. And he made little effort to hide that past. He never changed his name, and even handed the school his marriage license–registered at the Gross-Rosen camp, listing him by his SS rank, and stamped with a swastika and the Nazi imperial eagle–to get his wife on his insurance plan.

Kulle was an admitted and, it would turn out, unrepentant Nazi. And yet, friends and neighbors in one of the country’s most progressive suburbs were offering forgiveness that he had never asked for. I came to understand my initial question differently, that perhaps Americans were not defending Nazis, but sometimes defending themselves, or their communities. After all, if Kulle really was the monster OSI claimed, what did that say about the men and women who counted him a friend?

How has writing this book changed you, and what is next for you, now that this project is officially out in the world? Do you find that this project has affected your teaching? If so, how?

Thank you for asking about teaching! Throughout the research and writing process, I was constantly thinking about what I could bring back to my classroom. Sometimes, that was just a random tidbit I learned, or an interesting document I came across in the archives. Other times, it was something larger. I built a simulation that cast students as school board members navigating the Kulle Affair, which became the opening week of my Holocaust Studies course. Later, I designed a classroom simulation of the “Nazi hunting” process, which began by giving students a list of Dachau guards and a 1975 Chicago phone book.

Writing this book involved a lot of research, including archival work at Holocaust museums and at the National Archives. Being able to share that process with my students, giving examples of creative ways of adapting when I had hit dead ends, has been really helpful in the classroom. The book also put me back on the other side of the writing process–the vulnerable side. I was creating this thing, putting everything into it, and then handing it to someone else to evaluate. It was terrifying. At some point, on what felt like my 300th minor revision of my book proposal, my wife grabbed my arm and said, “No one is going to publish a book that doesn’t get proposed. Send it in.”

It was scary and humbling, and a really healthy reminder of what students experience on a daily basis. Finally, this project really reaffirmed the importance of finding ways for students to cultivate their passions and interests, for doing deep dives, for looking at history in unique ways that feel relevant and important to them. High school students don’t always have that opportunity, that chance to let their own interests guide their studies. And I just have to say that Tim Mennel and Matt Briones, my editors on this book, were the absolute best partners, as were the reviewers the University of Chicago Press selected. The four of them were the perfect combination of challenging and supportive, and I can only hope that I am as good a partner for my students as the team at the Press has been for me.

What are the big questions that fascinate you in your reading, research, and writing?

When I was in college, I was lucky enough to study closely with David Hackett Fischer, who always implored us to ask big questions and find small answers. That idea has really stuck with me. I love coming across a previously unexplored, minute story that, in some broader sense, embodies larger truths. I loved, for example, Dr. Kirsten Fermaglich’s A Rosenberg by Any Other Name, which used Jewish name changing practices as a way of studying Jews’ experiences with and perceptions of antisemitism. I am particularly interested in stories that explore the inconsistencies between values and actions, or narratives and realities. That tension is just so deeply human. Linda Kinstler’s beautifully written Come to this Court and Cry: How the Holocaust Ends, which welded Latvia’s attempt to rewrite Herberts Cukurs’s murderous past with the author’s attempt to uncover a family mystery connected to Cukurs, absolutely captivated me. While I occasionally read alternative history or dystopian fiction, I tend toward nonfiction, and am mostly interested in issues related to Holocaust consciousness, Holocaust education, and the peculiar mechanisms and manifestations of antisemitism.