Another week, another herd! Among this week’s Unicorns: an analysis of the difference your name makes on political party allegiance, Christmas in September, the war on humanity, several essays on poetry and immigrant literature, stay-at-home mom writers, the Midwest, and more.

***

Stories that names tell: WaPo has discovered a connection between certain names (whether first or last) and political preferences. A taste from the findings (which are fascinating):

Our initial tests showed that the most popular Republican-only names in the United States are Andy Byler, Steven Stoltzfus, Elmer Stoltzfus, Jacob Stoltzfus and Benuel Stoltzfus — each of which describes at least 37 registered Republicans and not a single Democrat.

Can you guess what’s going on? Then you’re way ahead of us!

Hilariously, in hindsight, Google didn’t show a huge online presence for any of them. But upon deeper inspection, we traced every Benuel and Elmer back to their own legitimate registration. So, we peered again at their addresses and soon everything made sense: Almost three-quarters were in Pennsylvania, and almost half of all of America’s Stoltzfuses live in just one county — Lancaster. …

Overall, the bluest names with at least 5,000 major-party voters are Imani, Latoya and Tamika for women and Jermaine, Darnell and Malik for men. On the other side of the political divide, we find Brayden, Colton and Tanner for Republican men and Darla, Misty and — ironically for the party of Lincoln —Dixie for women.

Incredibly, some names switch parties depending on whether you give them to a boy or a girl. Most women named Laverne are Democrats, while most male Lavernes register Republican. Tyler, Dylan and Toby see similar splits. Jean and Shelly swing in the opposite direction: A female Jean is more than twice as likely to register Republican as a male Jean would be.

***

A difficult but necessary read: Matthew Hall offers “A Chillingly Seductive Glimpse of Assisted Dying” in Canada, after witnessing the physician-assisted suicide of his aunt.

***

On the flip side, one technological entrepreneur is proposing that AI can end grief by “using artificial intelligence to recreate the essence of dead loved ones from their digital footprint.”

***

As an immigrant, I’ve been fascinated by Boris Dralyuk’s masterful stories and translations of the works of Russian immigrant poets—like this one, a delightful story of a poet I’ve never heard of before, Taisia Bazhenova, and one of her poems.

***

And then after reading the above, I read this, also from Boris Dralyuk: “From Dark Naked Fields: Yiddish Literature After the Pogroms of 1919.” A taste:

“On the dark naked fields”, writes the Yiddish-language poet David Hofshteyn in one of the lyrics in his debut volume, On the Road (1919), “in the middle a ditch lies / a threshold to nowhere in the desolate distance”. In the original the final line includes two occurrences of the word hefker, the concept at the centre of Harriet Murav’s innovative studyAs the Dust of the Earth: The literature of abandonment in revolutionary Russia and Ukraine. The term is rooted in rabbinical law, where it was first used to refer to ownerless objects, but through metaphorical usage its meaning has expanded over time. It has come to encompass states of the human condition, for we too can be unclaimed, ownerless, left radically free and, by virtue of that very freedom, radically vulnerable. As Murav notes, the range of meanings embedded in the notion of abandonment – one may be abandoned or act with abandon – gives anglophone readers a fair sense of the multiple valences of hefker.

Murav argues that, in the early twentieth century, hefker became “the watchword of poetic experimentation” among Yiddish-language writers from the Russian Empire. It holds a key to the works of Hofshteyn, his fellow modernist poet Leyb Kvitko and the novelist Itsik Kipnis, to whom Murav dedicates substantial chapters, as well as to those of the novelists Der Nister and David Bergelson, and the poet Kadya Molodowsky, whom she discusses at length. Through well-contextualized, convincing close readings, Murav analyses how these writers variously embraced a programme of artistic freedom, abandoning traditional realism and other outmoded schools while confronting the horrors of the Russian Civil War, which left the Jewish population of what is now Ukraine abandoned by any stable form of law and order, and rendered them vulnerable to a wave of pogroms in 1919 that claimed some 100,000 lives in the most brutal fashion.

I’m the first non-Yiddish speaking generation in my family, so this historical reminder is poignant. The reality Murav and Dralyuk write about is not so far removed.

***

Tales of other immigrants and cross-national poets: Anastasios Mihalopoulos’s double review, “Still on their Way: A Review of John Tripoulas’s Polytropos and Scott Cairns’s Correspondence with My Greeks.”

***

On another note, it used to be that people who wanted to be writers gravitated towards academia. But the family unfriendliness of academia along with the perfect storm of, well, no jobs, means that increasingly more women, in particular, are carving out a writing career outside of academe. Beatrice Scudeler is one such writer whose work I greatly appreciate. Here is her latest in Plough, telling her story of walking away from academia to focus on her family. But in the process, she found that the words came pouring! Also, be sure to check out Beatrice’s work here in Current.

***

Speaking of mom writers I admire: this week Ivana Greco reviewed Catherine Pakaluk’s book Hannah’s Children, which studies moms who have chosen to have 5+ kids. How are this 1% of American mothers different from the rest of us? Ivana offers reflections, but also reminds us that it’s no less essential to study the fathers in such conversations–hopefully Pakaluk might write a book about them next!

***

Also speaking of mothers and children, an interview about my new book this week in Deseret.

***

This article from Jon Lauck is open access for the next month: “The Contraction of History PhD Programs in the Midwest” in the latest issue of Middle West Review. A taste:

In 1991, for example, the University of Iowa history department brought in 31 new graduate students. In 1992 they brought in 25 and in 1993, my year of entry, they brought in another 20. These entering classes meant that departmental picnics and softball games and random parties were well-attended. Seminars were full. The graduate student offices were lively. Friday beer hour at the Dublin Underground on Dubuque Street was lit. It was a scene.

But because of the shrinkage of the market for PhDs in history, the University of Iowa has significantly reduced the number of graduate students it admits. For the fall of 2024, it admitted five PhD students, which is nearly a 90 percent decline from 1991. Iowa was not wrong to do this given the collapsing employment prospects for PhDs in history, but these numbers are quite stark, nevertheless. At a time when we are worried about the overall diminution of historical consciousness and the failure of the next generation to learn the basic facts of American and global history these numbers are worth pondering.

***

In the same issue of the Middle West Review, but not open access, you can still catch the first part of a delightful essay from Jeff Bilbro, wrestling with the difficult question: just what exactly is the geographical characterization to which his Western Pennsylvania home belongs? And why is this question even worth asking? A taste:

Since moving to Grove City, Pennsylvania, a small town about an hour north of Pittsburgh and less than half an hour east of the Ohio border, I’ve been fascinated by the challenge of identifying the region to which this part of the country belongs. Granted, regional monikers such as the Midwest, the Mid-Atlantic, or Appalachia blur and overlap. And each place is uniquely itself, a particularity that can be obscured by carelessly applied labels. But reflecting on the history and character of regions can also help us see and name their reality more accurately and, one hopes, inhabit them with care.

Yet as we settled into our new community, I soon realized that it had a very different history, topography, and flavor than the Midwest. And, of course, almost no one includes Pennsylvania in the Midwest region (though nine percent of Pennsylvanians did identify as Midwesterners in the recent poll conducted by this journal).1 I suppose some people around here put marsh-mallows in their salads, but the local staple at restaurants entails mixing in french fries instead.2 And if western Pennsylvania isn’t quite the Midwest, it shares even less in common with Philadelphia and its sprawling suburbs, or with Lancaster and its rolling farmland. Pennsylvania may technically fall within the Mid-Atlantic region, but that region doesn’t really fit our part of the state. I’ve finally settled on Northern Appalachia as the most accurate label for this area, and the distinctive history and topography implied by this label continues to shape the communities here.

The character of western Pennsylvania today is defined, in part, by who didn’t move here.

***

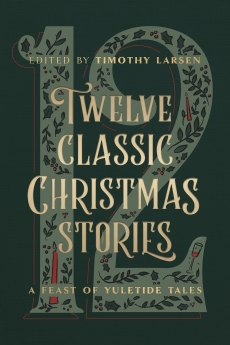

Last but not least, Current Contributing Editor Timothy Larsen brings to us the delight of Christmas in September—his new book is out: Twelve Classic Christmas Stories: A Feast of Yuletide Tales! My kids are very excited, and we will be reading this as a family read-aloud this fall.