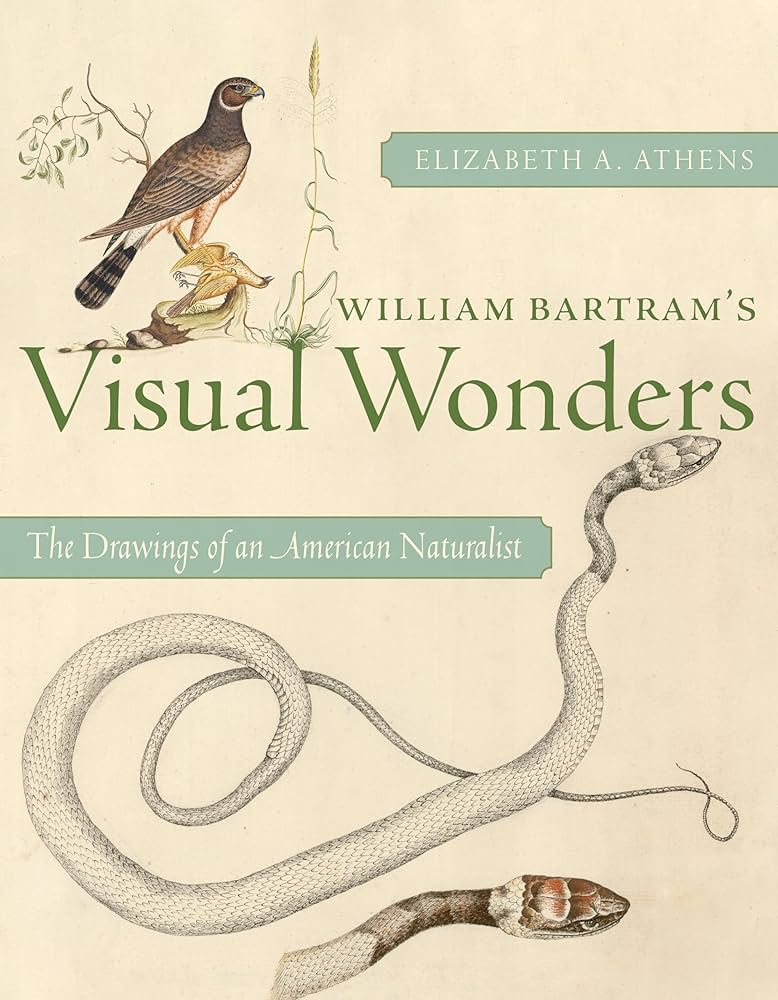

Elizabeth A. Athens is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Connecticut. This interview is based on her new book, William Bartram’s Visual Wonders: The Drawings of an American Naturalist (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write William Bartram’s Visual Wonders?

EA: My research interest in William Bartram began with a visit to Bartram’s Garden in Philadelphia fifteen years ago. I had no idea that such a placed could be situated within a major metropolitan area. My first visit was in late spring, and it felt almost like a hallucination or a dazzling vision: the sun was pouring through the trees and glinting off the Schuylkill, and the poppies were in riotous bloom. I left wanting to know more about this historic botanical garden and about the Bartram family. After I saw the drawings made by William—whose father, John, established the garden—it seemed an urgent challenge to make sense of their beauty and strangeness.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of William Bartram’s Visual Wonders?

EA: Bartram’s botanical and zoological drawings create a similar visionary feel as a visit to the Garden—you find yourself asking, what am I seeing? But the drawings’ peculiarities are, in truth, what helps us understand Bartram’s approach to nature: instead of hewing to the representational dictates of eighteenth-century natural history, they instead map out how he came to know a dynamic natural world, and they encourage us to participate in his process of exploration.

JF: Why do we need to read William Bartram’s Visual Wonders?

EA: For me, the most important element of William Bartram’s Visual Wonders is the close connection it articulates between art and science (to use this word anachronistically). We often see these fields as separate—if sometimes adjacent or overlapping—but for Bartram art and science were nearly synonymous. His drawings’ sudden shifts in scale, unexpected flourishes, and narrative detail don’t run counter to the scientific thrust of his work but underpin it. And Bartram wasn’t alone in how he portrayed the world; in fact, I argue that the work of English artist William Hogarth provided him an important model.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

EA: My approach to Bartram’s drawings is that of a historian of visual and material culture, not that of a historian of North America. It’s important to note that Bartram’s scientific interests—though he was born in colonial Pennsylvania and died in the United States—were not geographically delimited. Researching Bartram has revealed how essential it is to be closely attuned to both the local and the global in writing history: he worked in a very specific time and place, but he was also part of a continents-spanning network of artists, doctors, gardeners, merchants, and naturalists, all of whom had distinct commitments and motivations.

JF: What is your next project?

EA: My next project, Material Matrix, again braids together the histories of art and science, but rather than focus on the work of a single artist, it examines three inflection points in the history of science and printmaking, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. With this book I hope to show that technical and stylistic developments in print media did not just convey new scientific concepts, but also helped lay the groundwork for their development. I have a fellowship at the Institute for Research in the Humanities (UW-Madison) this year, where I am researching the book’s first chapter on sixteenth-century anatomical woodcut illustrations.

JF: Thanks, Elizabeth!