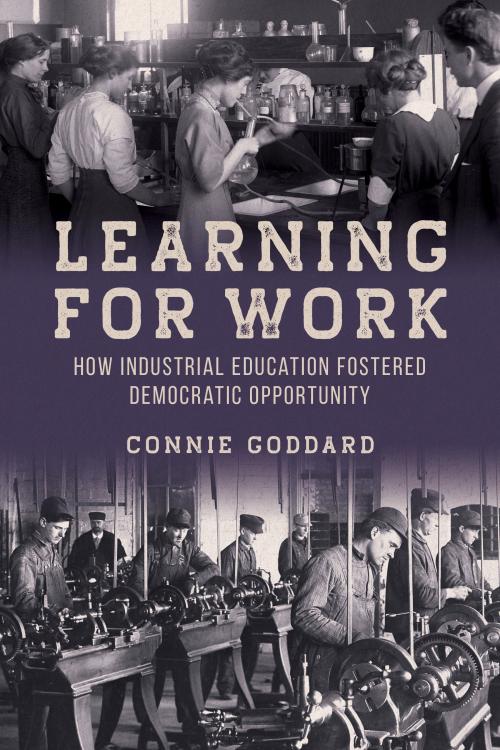

Connie Goddard is a journalist and independent scholar. This interview is based on her new book, Learning for Work: How Industrial Education Fostered Democratic Opportunity (University of Illinois Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write Learning for Work?

CG: There were several influences; the primary one may have been teaching composition and U.S. history at a state prison in New Jersey. That experience led me to ask why my students were on the inside and I was free to come and go. Among the reasons was that too many of them had not had an opportunity to learn how to make a living without getting in trouble with the law. At around the same time, I learned of a school that once existed in Bordentown, about ten miles down the road from where I was living in Trenton. Called the Manual Training and Industrial School (MTIS), its curriculum was a mix of ideas articulated by W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, and John Dewey. As a student of all three, I wondered why I’d not heard of MTIS before: might an education such as it offered have set my students lives off in a more productive direction?

Those questions set me off on a journey that led to this book. Others were my study of Dewey’s work in Progressive Era Chicago. One of the programs under his charge at the university was the Chicago Manual Training School (MTIS). Though he was a great advocate for the kind of industrial education offered by CMTS – that of the head and the hand complementing each other – he largely ignored it while it was under his purview. Figuring out why he had done so became another reason for writing this book.

A third major motivation was an effort to persuade some fellow historians of schooling that industrial education, at least as practiced during the Progressive Era, was an effort to extend democratic opportunities to children from less-privileged families. A contrary interpretation has predominated over several decades; I felt that this was not only wrong-headed but a disservice to the intentions and accomplishments of people who endeavored to encourage young people to remain in school, in part by offering them training in ways to make a living.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Learning for Work?

CG: Industrial or vocational education – or combining the work of the head and the hand in schooling — actually has a long history; its roots in the US go back to the “log colleges” of colonial America, to the manual labor movement represented by abolitionist Theodore Weld, to the origins of land-grant schools, and the manual training movement advocated by Calvin Woodward. It has also been a means of extending opportunities for young people by encouraging them to be, in the words of John Dewey, “masters of their own industrial fate.”

JF: Why do we need to read Learning for Work?

CG: Though I didn’t anticipate an international pandemic when I began to formulate this book, the ramifications of Covid make its arguments increasingly pertinent. Whereas “college for all” has been a mantra for several decades, years of “virtual” schooling have called that necessity into question. But what are the alternatives and what can history teach us about how, what might work best, and why? Learning for Work offers some lessons. Further, as a society we are considering the plight of boys and young men who are underemployed, dropping out of school, and anxious about their future. At the last century’s turn, the early 1900s, reformers looked to the schools for an appropriate response to a similar problem – boys dropped out at 13 or so, before they were prepared to be productive citizens. What could be done to encourage them to remain? Manual training and vocational education were among the more successful responses; by the 1920s, industrial education courses had been incorporated into comprehensive high schools. Enrollment in them grew markedly, for girls as well as for boys.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

CG: I’m tempted to reply that I cannot recall when I wasn’t. I suppose it began with family stories – I am privileged to come from one in which they abound. And when I was born, three of my great-grandparents were still living; all had been homesteaders in the Dakotas. Where did they come from and why? What was their legacy to my parents and my siblings? Actually, the Normal and Industrial School my mother attended in North Dakota, her high regard for it and the other schools (beginning with a one-roomer) in her background, plus my having attended a famed progressive school (Crow Island in suburban Chicago), all contributed to my interest in the history of education. Why did this or that happen in a particular way? What are the regional (and religious) differences in attitudes toward and support of public schooling? History begins with questions, and I have been privileged to be able to study enough history to answer some of them – as well as develop several more.

JF: What is your next project?

CG: Ah, where to begin? For one, I’d like to do a young adult biography of Ella Flagg Young, the brilliant and gifted educator who by 1910 had become one of the nation’s most admired administrators, politically savvy educator, theorist, and the person who taught Dewey how schools operate as social institutions. She was the topic of my 2005 dissertation, and I’d like to get this written for my granddaughters – before they become adults. Also, my work on schooling in the Dakotas has made me aware of another educator of consequence, William Henry Harrison Beadle, who helped to build a thriving school system during the Great Dakota Boom of the 1880s. Young is more well-known than is Beadle, but he deserves some national recognition as well.

JF: Thanks, Connie!