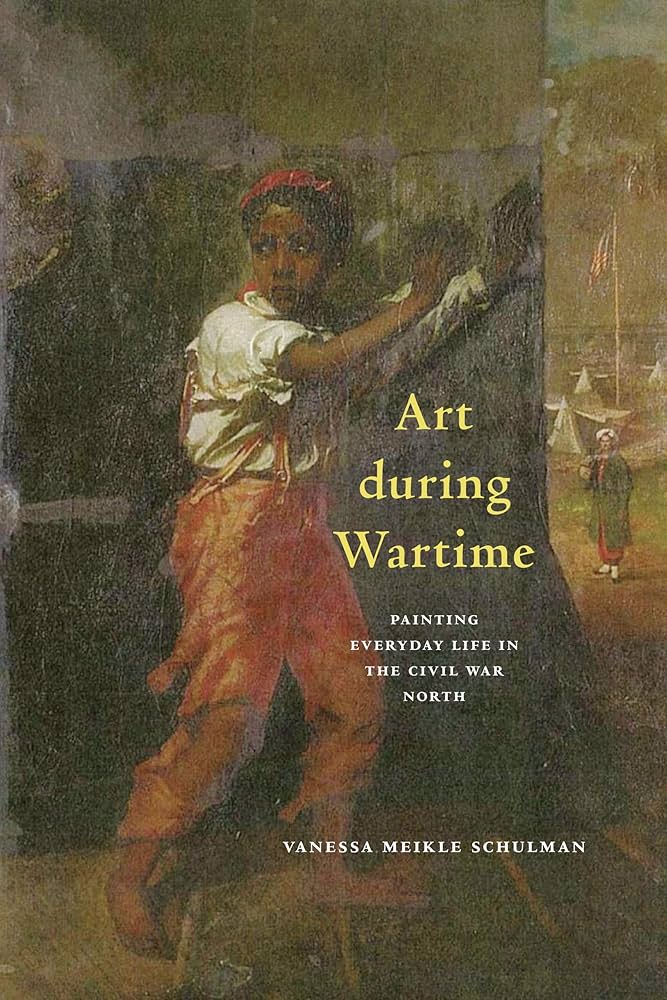

Vanessa Meikle Schulman is Associate Professor of Art History at George Mason University. This interview is based on her new book, Art during Wartime: Painting Everyday Life in the Civil War North (University of Massachusetts Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write Art during Wartime?

VS: I originally intended to write a book about Civil War photography, but while teaching a course I designed about Civil War culture, I became increasingly interested in paintings. Everyone (at least, every art historian) knows Winslow Homer, and we tend to treat his Civil War paintings as if they are unique. But they aren’t: while teaching the class for the first time, I realized just how many artists were making paintings of “everyday” wartime and home front events. So I rethought the project. I wanted to refocus the scholarly conversation about Civil War visual culture. It’s not just Mathew Brady and Harper’s Weekly and Homer. There was a vibrant artistic sphere in the north whose participants were using painting to comment on how the war upended cultural norms and reframed social categories.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument Art during Wartime?

VS: Genre paintings, or images of events from everyday life made in a visually realistic style, were a central form of northern, patriotic artistic production during and immediately after the American Civil War. While artists failed to produce effective battlefield scenes, genre paintings successfully reflected, and shaped, changing notions about gender, race, citizenship, and physical ability, as I show in case studies of seven paintings made between 1862 and 1867.

JF: Why do we need to read Art during Wartime?

VS: I think it will give historians a different perspective on the Civil War home front and the ways that visual culture, particularly painting but also news illustration, popular prints, and sheet music, promoted certain narratives about race, gender roles, and disability. The war unsettled these categories, which had been key to pre-war genre art. Paintings representing soldiers and home guardsmen constructed new notions of masculinity. Images of Black men, both civilians and soldiers, presented expanded definitions of participatory citizenship. Representations of women in domestic spaces reflected on female contributions to the war while preserving normative ideals of femininity. And renderings of wounded soldiers asked viewers to consider the value of sacrifice. Understanding these paintings gives us insight on how northern cultural elites imagined the patriotic work of wartime.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

VS: I’m not really sure! Maybe in third grade, when I dressed up as Paul Revere for Halloween? My father was a professor of American studies, so from a young age I realized this was something a person could “be” when they grew up. My degrees are in Art History/American Civilization (BA) and Visual Studies (MA/PhD), but I also took several U.S. history courses in graduate school. I’ve always felt that to analyze American art successfully and understand how it operated in its time, you need a solid foundation in historical and social contexts. But professionally I don’t really consider myself a historian—I’m a scholar of American art and visual culture.

JF: What is your next project?

VS: I am working on a new book about how painters represented ecological issues in New York City around the turn of the twentieth century. I’ll be looking at how they depicted air and water pollution, public transportation and infrastructure, human-animal interactions, and extreme weather events.

JF: Thanks, Vanessa!