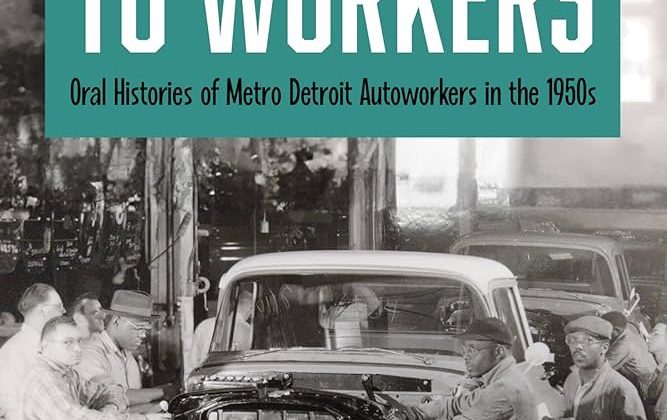

Daniel J. Clark is Professor of History and Director of the Center for Public Humanities at Oakland University. This interview is based on his new book, Listening to Workers: Oral Histories of Metro Detroit Autoworkers in the 1950s (University of Illinois Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write Listening to Workers?

DC: This project stemmed from my long-term interest in contributing to the social history movement by exploring history “from the bottom up,” from the perspectives of ordinary people who were not famous. Despite all that has been written about the auto industry and the United Auto Workers (UAW), not much is known about the lives of ordinary autoworkers, how auto jobs and the union looked from the bottom up. Scholarly attention on autoworkers has focused mostly on activists or leaders, particularly Walter Reuther, the longtime president (1946-70) of the United Auto Workers. The literature contains little evidence directly from ordinary workers and often considers them mostly in terms of their relationship to the bargaining agendas of top-level UAW officials. In hopes of learning more about ordinary autoworkers, I began an oral history project in the early 2000s. That was about as far back in the past as I could go and have a realistic chance of finding people, then in their 70s and 80s, who had been at least young adults at that time. It was also a decade recognized by historians and the general public as the heyday of the auto industry and the UAW.

No research project proceeds according to plan, though, and this one was no exception. While listening to the first twenty or so interview recordings, I wondered why so many of these former autoworkers, white as well as Black, recalled the post-WWII years as economically unstable and insecure. This unexpected discovery led to years of research in Detroit newspapers to see if local coverage would corroborate or contradict what interviewees recalled. As it turned out, the newspaper evidence overwhelmingly confirmed the oral history recollections and became the backbone of a book, Disruption in Detroit: Autoworkers and the Elusive Postwar Boom (University of Illinois Press, 2018). Evidence from my oral history interviews does appear in Disruption in Detroit, usually in brief excerpts to support my larger argument about persistent instability and insecurity. But readers of Disruption in Detroit won’t learn in any sustained way about who the interviewees were, what they wanted from their lives, what struggles they faced, and how they coped. They deserved to have their stories told in much greater fullness, and that’s what led to Listening to Workers.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument Listening to Workers?

DC: Ordinary autoworkers in the early post-WWII years were complex, multidimensional people, with a wide range of aspirations and concerns. Their lives were much richer, more interesting, and at times more confounding than we can tell from the existing literature.

JF: Why do we need to read Listening to Workers?

DC: The complexities in this sample of 1950s metro-Detroiters suggest how daunting the challenge would be to truly understand the history of autoworkers. At various points in the fifties, there were as many as 500,000 Detroiters involved in auto work, including old-timers and recent arrivals. Their stories are the history of autoworkers in that era, but as for how most of them lived their lives, only their friends and family members will ever know, and such memories often barely survive the next generation. These narratives have great value precisely because they are suggestive of the complexity of desires and experiences among ordinary autoworkers.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

DC: I became an American historian because of my experiences as an exchange student at the University of Sussex, in England, which showed me that it was possible to become a historian, and the pathbreaking work being done by American historians like Bill Chafe, Larry Goodwyn, and Peter Wood at Duke University in the 1980s. But it is hardly clear that one can become a historian just by wanting or hoping to become one, and I reduced my chances (and I’m glad I did) by staying home to raise my two sons for a few years when they were very young. After years of part-time and temporary teaching while regaining a toehold in the profession, and publishing my first book, Like Night and Day: Unionization in a Southern Mill Town (University of North Carolina Press, 1997), I landed a tenure-track position at Oakland University, just north of Detroit, in 1999. That was an important “when.”

JF: What is your next project?

DC: I’m nearing retirement, so my next project might involve historical research or it might have more to do with the community garden that I coordinate. In the meantime, I’m involved with an oral history project focused on Pontiac, Michigan.

JF: Thanks, Daniel!