Educators could benefit from a very close reading of Calvin and Hobbes

Becoming Homeschoolers: Give Your Kids a Great Education, a Strong Family, and a Life They’ll Thank You for Later by Monica Swanson. Zondervan, 2024. 240 pp., $19.99

Virtually every parent and truthful observer of an elementary school classroom will tell you that the average boy has special needs and gifts that are distinct from the average girl. This is a generalization, of course. Each child is unique, and each one deserves to be supported and educated in a way that works best for her or him. The centuries of human history in which cultures failed to educate their girls in preference for boys are thankfully (mostly) behind us.

Unfortunately, the modern educational system in the U.S. seems to be particularly failing its boys. Richard Reeves, who recently founded The American Institute for Boys and Men, has presented persuasive evidence that boys are falling behind in schools. Reeves writes that “[g]irls are 14 percentage points more likely than boys to be ‘school ready’ at age five.” Boys are less likely to achieve proficiency in reading by the end of middle school, with an “11-point gap by the end of eighth grade.” They are also less likely to graduate from high school, leaving Reeves to conclude that “at every age, on almost every educational metric . . . girls are leaving boys in the dust.”

Contra these depressing statistics, the four sons of Monica Swanson, a homeschooling mother with two decades of experience and the author of a new book, Becoming Homeschoolers, seem to be thriving. Her oldest three sons are now successful young adults (one a college graduate, one in college, and one combining a surfing career and online college), while the fourth is twelve years old. What is her secret?

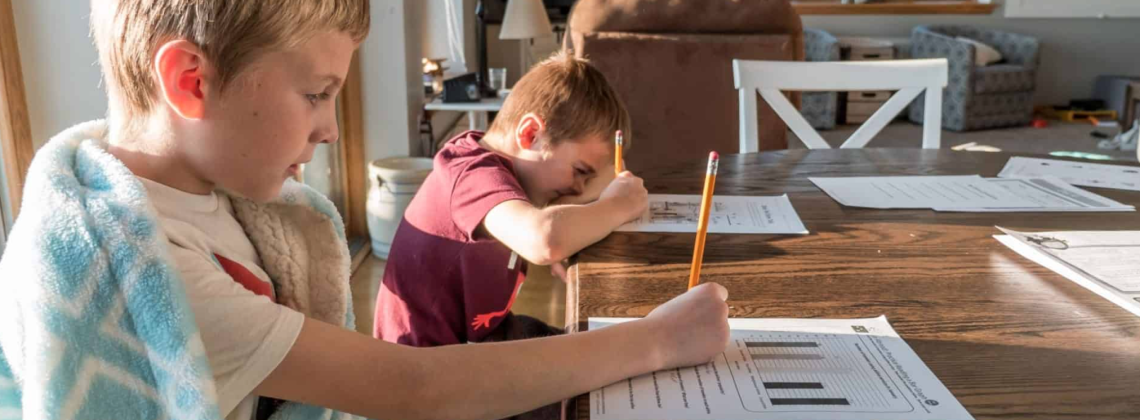

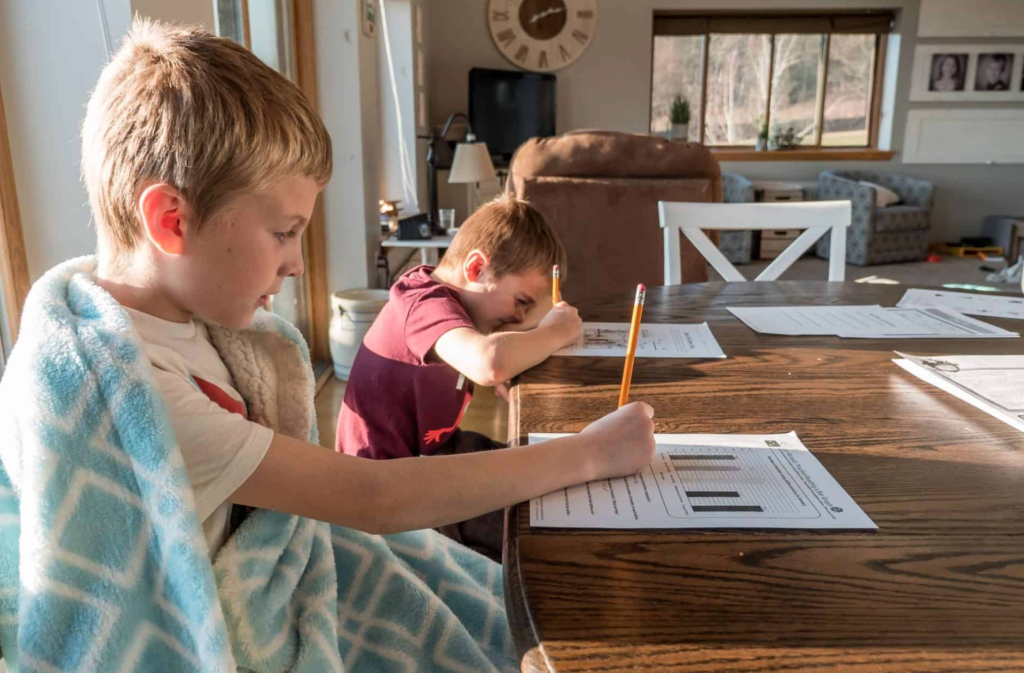

First, Swanson encourages parents not to push formal academics and extracurriculars too early but to tailor the speed of education for each child. For kindergarten through third grade, she recommends that parents maintain a “healthy balance of structured activities and plenty of relaxed time at home” with “unstructured play” remaining “the most important part of your child’s day.” In the upper elementary years she suggests tailoring reading assignments to topics the child considers interesting. She writes, “One of my sons loved science fiction novels, while another was drawn to true stories.” Her third son preferred graphic novels and survival stories. As for math, Swanson suggests, “It might be wise to figure out how much time your child is able to spend on math before they fizzle out, and then set a timer for that.”

This slow introduction to formal education, tailored to the interests and abilities of each child, reflects the findings of recent scientific studies on childhood development of boys. As Jennifer Fink writes in Building Boys, “boys’ brains take longer to mature, and an average five-year-old boy is significantly less developmentally ready to sit still, write, and read than the average five-year old girl.” Pushing boys into formal education before they are ready can taint their entire educational experience. As Fink points out, “A child whose early school experience is one of frustration, discipline, and humiliation is unlikely to feel enthusiastic about school.”

Second, Swanson encourages home educators to meet their boys’ needs for physical activity. Swanson’s sons are serious athletes. One son “began to dedicate many hours a day to his surfing career during middle school.” Homeschooling allowed him to “arrange his own schedule.” Another son “is an avid golfer, and he enjoys the freedom to golf and to plan his schoolwork around the weather, his coaches and all the other factors involved in sports.” Indeed, sports and physical activity are so important to Swanson’s family that she devotes an entire chapter to the topic, because “Making regular movement and fitness a normal and required part of your kids’ day is one of the greatest gifts you can give them.”

Contrast this with the amount of physical activity available to boys in traditional schools. Even states that mandate recess often only offer twenty to thirty minutes daily of outdoor, unstructured playtime. Timothy Walker, a long-time teacher, notes that when he taught in U.S. schools, “Many of my students—after spending hours inside our classroom—used to struggle with behavior and attention issues.” Walker used various strategies to help his students cope, including “brief songs, poems and games.” Ultimately, though, he concluded that “More than anything else, my American students needed more opportunities for unstructured play breaks (ideally outdoors).”

For devoted readers of the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, this dynamic will be familiar. When Calvin is playing outdoors, he is acutely interested in ideas and the world around him; he is fully alive. In scenes where Calvin is in school, he is a tragic-comic figure, trapped at his desk while his teacher drones on and he escapes into fantasy daydreams. Is Calvin learning anything in this scenario? Based on the running theme that his most frequent grade is “F,” and the number of times he is sent to the principal’s office, it seems that the answer is no.

Third, Swanson encourages parents to let boys remain little while they’re young—but also provides strategies to help them confidently transition into adulthood when they are ready. She believes homeschooling helped insulate her boys from the pressure to grow up too quickly. When her boys were young, they wore Spider-Man costumes to lessons and engaged in creative play (read: Legos) throughout the day long after most of their peers stopped dressing up and playing with toys. As they got older, homeschooling also helped her boys prepare to become self-sufficient. For example, the kids were able to “get work experience during the school day when most students [were] stuck in a classroom.” One of her sons interned in a surfboard shop during the school year. He worked enough hours to be “paid” with a new, expensive surfboard. Swanson recorded the experience as a business internship on his transcript. The shop’s owner also wrote a glowing letter of recommendation when this young man applied to a college program that would let him combine his budding career as a professional surfer with academic studies.

Compare these fruitful high school years with the supposedly “progressive” view of “college for all” enshrined in our modern system of public education. Little thought is given to the boys who are ill-suited to a purely academic high school experience followed by years at a traditional college. In their essay “College is Not for All,” Oren Cass and Wells King write that enormous emphasis is now placed on preparing every high school student to matriculate at a four-year college. Simultaneously, the federal government strangled funding for those on alternative paths. As Cass and King point out, “The share of federal K-through-12 spending on career and technical education fell from 12 percent in the 1980s to 3 percent today.” They go on to observe, “Across all levels of government, we now spend more than $200 billion annually to subsidize higher education while, for those not on the college pathway, we offer a firm handshake and the best of luck.” This shift away from vocational training seems to particularly disadvantage boys, according to Reeves. He notes, “[T]he wages of most men are lower today than they were in 1979, while women’s wages have risen across the board.” Working class men are left unprepared to find stable, well-paying jobs—even while employers in the skilled trades are increasingly desperate for good job candidates.

Fourth, and perhaps most important, Swanson emphasizes that homeschooling offered her the opportunity to recognize the inherent worth and dignity of each of her sons as she helped them discover “who God made them to be.” While she does not put it exactly this way, the reader is left with the sense that Swanson was able to see the imago Dei in each of her children and to support the unique individual bearing it.

This perspective is invaluable in a society that increasingly sees the unique qualities of many boys—their rough and tumble play, their insatiable curiosity, their refusal to back down from a fight—as downsides, rather than potential virtues needing to be channeled and directed productively. The popular lesson-planning website, Teachers Pay Teachers, for example, contains many plans for high school teachers to help reduce “toxic masculinity.” While such lessons are doubtless well meaning (and rightly recognize that certain conceptions of masculinity can be poisonous), they leave many teenagers with the sense that our society is one in which it is not good to be a man.

And they’re not wrong. To take an extreme example, one of the most disturbing current trends in IVF is sex-selection in embryos—in preference for girls. An article based on interviews with more than a dozen parents who wanted to use IVF to sex-select for females revealed that these parents believe “boys are incapable of doing their own laundry, calling their moms, expressing empathy, or even really being part of the family as they get older.” Prospective parents worried about having boys because of “toxic masculinity,” and because “men [are] lagging in almost every metric that matters to success-obsessed [parents].”

In place of this bleak view of boys, Swanson offers a better one: Parents should nurture sons and guide them into manhood in a way that encourages their talents, interests, and agency. As a mother of three sons (one in utero) and a daughter, I was encouraged by Swanson’s conviction that it is still possible to educate young men in a way that leaves them with a sure sense of their own self-worth, along with (as the poet writes), the knowledge that

I am the master of my fate

I am the captain of my soul.

Ivana Greco is a homemaker and homeschooling mother of three, as well as an attorney. She writes at: https://thehomefront.substack.com.