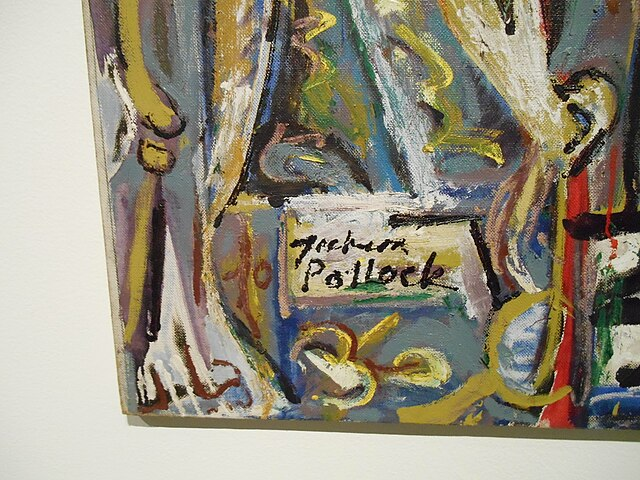

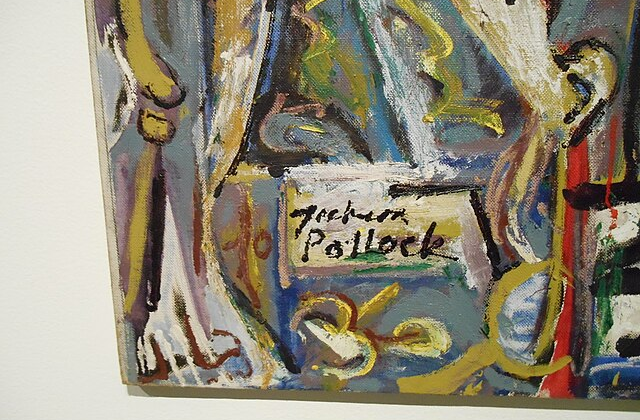

As he was developing his technique and growing in fame, Jackson Pollock realized he needed to “get a group together.” He needed a group of other artists to associate with, to talk about art with, to compete with, to smoke cigarettes with, and to make progress. His group was in some ways a subgroup, because the abstract expressionists, also known as the “action painters” were already something of a group. As different as their personal styles were, they had things in common and saw each other quite a bit. They had mostly studied at the Art Students League, most of them had worked for the WPA during the Depression, and many of them gathered regularly, at places like the Waldorf Cafeteria and the Cedar Tavern.

What artists seem to know best is that the isolated genius is rare. To continue to develop and make progress in your field–you’re best off with some peers. The foil to the abstract expressionists in 1950s New York City were the European surrealists, who had fled Europe during the war and remained a group in New York. But almost every major art movement includes artists who had some contact with each other. The Impressionists spent time together. Many of the Italian Renaissance artists knew each other. It is not required that these associations be solely based on friendship. We might not have Brunelleschi’s dome without his intense rivalry with Ghiberti. We would have a different Raphael if he was not always referencing Michelangelo.

When we think of modern literature, our thoughts go to Paris in the 1920s. Why? Who was there? Everyone. Hemingway, Fitzgerald, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Getrude Stein—and they knew each other. The connections were valuable not just for networking, but for encouraging each other, consciously or unconsciously. The presence of other creative people can spur on more creativity and create opportunities. This is one of the reasons why cities are host to more creativity than rural places. Rural places are beautiful and they have their geniuses, but the biggest ideas typically come from cities—where there is a higher concentration of people making and doing and able to bump into each other and collaborate and/or compete.

The new YETI short All That Is Sacred is a look at 1960s and 70s Key West. It was a party town, it was a fishing town, it was a creative town. It was where Tom McGuane, Jim Harrison, Jimmy Buffett, and Richard Brautigan all hung out, among others. They fished, they drank, they wrote. They were both a bad and a good influence on each other. But the combination of friendship and competition pushed them to greater achievements, especially Tom McGuane and Jim Harrison. It was a special time and place, not just because of what Key West was then but because of who was there at the time.

Consider music. Where would jazz music be without competition and collaboration? What if Benny Goodman had never wanted to be “the best” and had just played for his family? Imagine if no one had tried to compete with the Chick Webb Orchestra and there were no matchups at places like the Savoy. And if you know much about jazz music history, you know that many of the best artists would meet up after gigs and continue to play, especially with people they did not regularly perform with on stage. Some would skip meals to improv with others. Iron sharpens iron. Thelonius Monk and John Coltrane made each other better. So did Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

The importance of a group extends far beyond the arts. The importance of close groups of friends and rivals is shown in the surf documentary, The Momentum Generation (2018)—about Kelly Slater, Rob Machado, Taylor Knox, Shane Dorian, and others. They grew up together, they surfed together, they surfed against each other. You can see the significance of a crew in two of Stacy Peralta’s films about skateboarding, Dogtown and the Z-Boys (2001) about the Zephyr Team which transformed street skating and invented getting “air,” and Bones Brigade (2012) about the Bones Brigade. Even once-in-a-generation talents like Tony Hawk developed in company with others. Even a loner like Rodney Mullen benefited from being on a team.

“If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” It is an old proverb, but it applies in more areas than people might realize. For those who want to get somewhere with something, they are better off knowing some other people trying to do something similar. You’re unlikely to reach the edge all on your own. You’re unlikely to reach your full potential with no one to talk to or try to beat. Whatever it is you really want to do, you’ve probably got to get a group together.