The Confederacy’s slave markets help us grasp the cost of freedom

On November 28, 1863, three days after Union forces broke the Confederate Army of Tennessee’s siege of Chattanooga and forced it to retreat into north Georgia, the Atlanta-based Baptist Banner printed a missive from one Elder J.R. Graves.

Graves, once a Nashville resident, had fled the United States’ occupation of that city and now served as an itinerant missionary in the Confederate states west of the Mississippi River. His letter offered both an update on his evangelical labors and a cri de coeur against what he saw as the fundamental problems plaguing the insurgent nation.

Prominent among these stood the “outrageously exorbitant prices” to which the hyperinflation wracking the CSA had driven virtually all goods. These soaring costs, which Graves attributed primarily to speculation by unscrupulous merchants, represented “the most fearful feature of this war” because they revealed “the rotten, avarice eaten patriotism of the masses of our people” (though one wonders whether many would not have considered the imminent collapse in Tennessee somewhat more “fearful”).

Graves’ answer for the crisis of confidence in the Confederate currency was straightforward: The readers of the Baptist periodical—particularly those with influence through the Rebel “press and the pulpit”—should shore it up by “thunder[ing] into the ears of the people, that Confederate money is as good as any property they call their own.” Specifically, they should tell their hearers it was as good as “their negroes or their land.” For, if the Confederacy were to fail, neither Rebel currency nor these assets would be worth anything.

It might seem strange for a self-proclaimed “religious and family newspaper” to hold forth on the relative and patriotic value of Confederate currency and enslaved people as investments. But such considerations weighed heavily on the minds of its readers.

Indeed, two columns over from Graves’s letter appeared a lengthy advertisement for Crawford, Frazer & Co., an Atlanta outfit of commission merchants and auctioneers specializing in the sale of commodified humans. Besides promising its customers access to a “negro yard and lock-up” (“safe and comfortable,” the firm assured them, neglecting to mention who, precisely, found it so), its proprietors touted their “experience in the business since our boyhood TO HANDLE THE NEGRO PROPERLY.” Crawford, Frazer & Co. was hardly the only firm to advertise for the sale of human property in the Baptist Banner. Other issues included ads by merchants like Seago & Davis, Amoss, Ligon & Co., Mayer, Jacobe & Co., and Thomas F. Lowe & Co., all of whom proclaimed their willingness to trade in people.

What explains the juxtaposition of these religious, patriotic, and mammonistic pieces in a Baptist newspaper? Equally importantly, what explains their appearance during the conflagration of the Civil War? These are some of the questions my book, An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South, seeks to answer.

In many ways, it was the context of the conflict that produced this flurry of advertisements, for the Civil War had profoundly changed life in Atlanta. The city boomed during the war thanks to its critical position as a transportation hub and a manufacturing center. Its once-modest slave market experienced a surge in demand for enslaved workers. Because “negroes are scarce,” commanding “the tallest kind of figures,” one periodical reported, traders like “Crawford Frazer & Co. are becoming an institution.”

Atlanta also became an outlet for slaves forced out of threatened parts of Georgia or conquered parts of Tennessee. Once purchased in the city, enslavers sent many to the factories, ironworks, and other shops that clothed and outfitted Confederate soldiers. With major pre-war slave markets like New Orleans, Natchez, Memphis, and Nashville in Union hands by the middle of the conflict, Atlanta also picked up some of the slack their fall created in the slave trade. By the Civil War’s third year, the scale and scope of its slave market had made Atlanta one of largest Confederate slave dealing centers.

The juxtaposition of Graves’ letter and slave traders’ advertisements also speaks to the ideological links between slave commerce and the Confederate endeavor. In many ways, the domestic slave trade was an avatar for the broader Confederate effort to establish an independent slaveholding republic. Not only did slave brokers contribute materially to the Confederate cause (in September 1863, for instance, Crawford, Frazer & Co. hosted a fundraiser for the relief of Confederate soldiers wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga), but, as Graves indicated, the demand for enslaved people served as a barometer for Confederates’ evaluation of their chances of prevailing.

It is telling, for example, that in response to the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation the Confederate press touted the robust activity taking place in the CSA’s slave markets. Even the specific people some Confederates sought to purchase required faith in the CSA’s eventual success. These included young women and children who would not be profitable for enslavers during the conflict itself, but whose value they expected to soar after victory.

Little wonder, then, that Solomon Cohen, one of Crawford, Frazer & Co.’s competitors, proudly touted a group of “75 Likely Young Negroes” he had on hand during the fall of 1862. Nor that a soldier in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia encouraged his father to “buy boys & girls from 15 to 20 years old” but to “take care to have a majority of girls,” given that the resulting “increase in number of your negroes by this means would repay the difference in the amount of available labor.” The slave trade and the Confederacy were bound up with one another—sufficiently so that this entanglement reached the pages of the CSA’s Christian press.

Less than a year after the Banner printed Graves’ letter, William T. Sherman’s forces seized Atlanta. When the Union general abandoned the city, bound on his famous “March to the Sea,” he consigned slave jails like that of Crawford, Frazer & Co. to the flames. Though the firm’s partners persisted in the slave trade—Robert Crawford in Macon, Thomas Frazer in Montgomery, Alabama—the Confederacy’s—and the slave trade’s—days were all but numbered. Union victory eventually fulfilled Graves’ prediction, rendering both enslaved property and Confederate money worthless. The slave trade was no more.

In the war’s aftermath, its former victims celebrated its demise while also mourning its existence and seeking to heal the wounds it had inflicted. In 1866 Cinda White posted an advertisement of her own in the South Carolina Leader, an African American newspaper published in Charleston, South Carolina. She sought three of her children, Sally, Jane, and Hercules. A man named Jack Wallace had sold Hercules in Atlanta at roughly the same time that the Banner had published Graves’ letter and Crawford, Frazer & Co.’s advertisement. Around the same time her two girls may also have passed through the city’s slave markets bound ultimately for Thomaston, Georgia. She hoped that by posting in this newspaper, which circulated widely in South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina, she might reunite her family. Whether or not she was successful remains unknown.

Today the stories of both the wartime slave trade and those whose lives it shattered remain relatively unknown. Little survives of Atlanta’s former slave trading district; the Five Points MARTA station stands on the site of Crawford, Frazer & Co.’s jail, and most pass through it unaware of the location’s history. Similarly, the experiences of people like Cinda White and her family, divided on the edge of freedom, often have been lost in a broader impulse to celebrate the freedom the Civil War wrought and are only now being recovered (thanks in large part to digital projects like Villanova’s “Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery”). Reconsidering the pervasiveness and widespread impact of slave commerce on Civil War South thus necessarily reconfigures our assessment of the purposes and progress of that conflict and allows us to weigh anew the cost of the freedom it produced.

Robert K. D. Colby is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Mississippi and the author of An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South

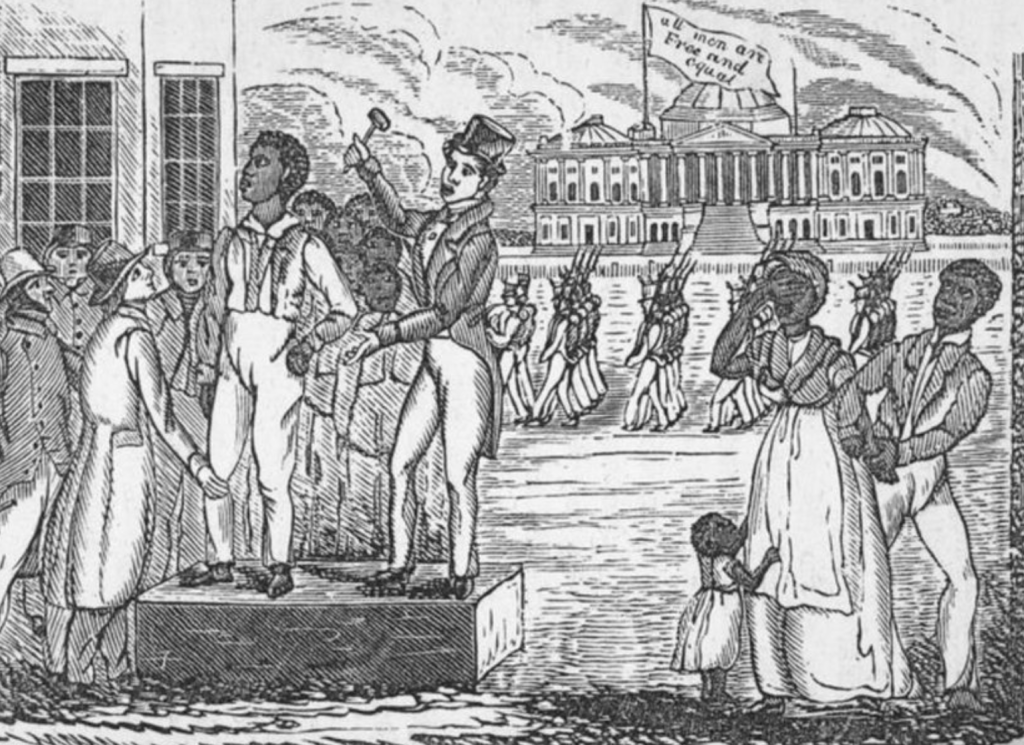

Image: Slave Auction, Charleston, South Carolina, Wikimedia Commons