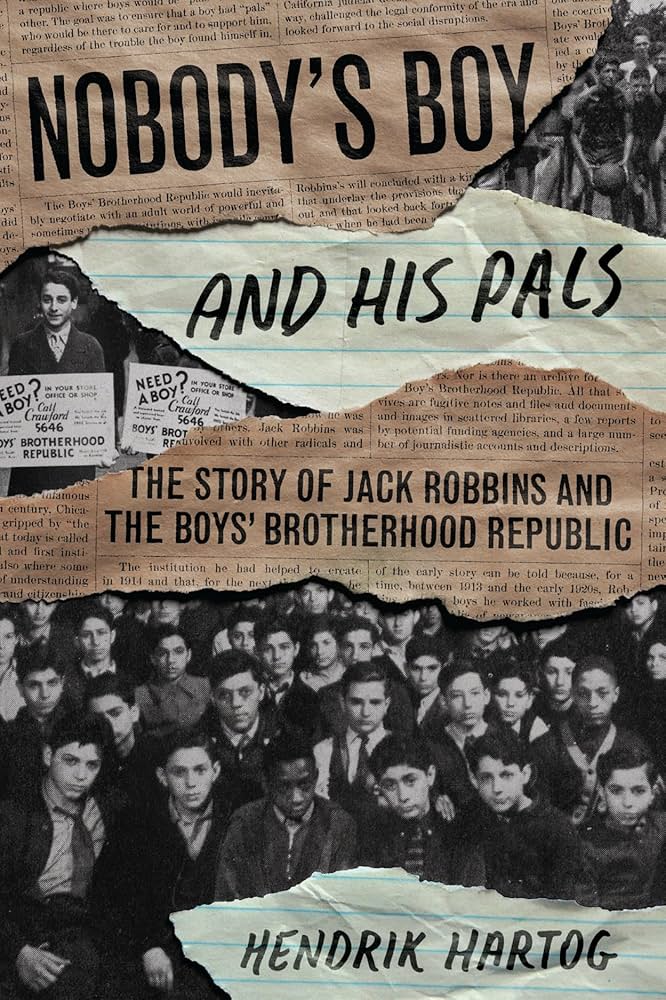

Hendrik Hartog is Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, Emeritus at Princeton University. This interview is based on his new book, Nobody’s Boy and His Pals: The Story of Jack Robbins and the Boys’ Brotherhood Republic (University of Chicago Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write Nobody’s Boy and His Pals?

HH: I began the book because I was reading postwar Cold War era property law casebooks for another project (which will be my “next” project — see question 5), and I came across a 1962 California case about an unknown individual who had left a small estate to the “Negro child or children” of someone who had been arrested or convicted for “political” crimes. The case told a good story about changing understandings in the law of political crimes and civil disobedience. And then I wanted to find out who was this unknown individual, Jack Robbins, who had made this weird will. That took quite a bit of work, but eventually I discovered that in the Progressive Era, in the years before and during World War I, he and the institution he created, Chicago’s Boys’ Brotherhood Republic (the BBR), were the subjects of literally hundreds of newspaper articles. Thanks to the wonders of online databases I could follow Robbins, an itinerant radical and salesman, who was known as the “big brother to chanceless waifs,” as he traveled around the country advocating for adolescents, claiming to have solved the “boy problem” of the era, telling his story to innumerable newspaper editors and reporters.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Nobody’s Boy and His Pals?

HH: The book is less an argument than a narrative that uses Robbins’s life and that of the BBR as a lens to explore changing understandings of childhood and city life and care across a half century of American history. Along the way, it brings to the surface an alternative (small d) democratic institution, the BBR, including its “constitution” and its ways of operating, that challenged conventional, mainstream understandings of crime and punishment and civil disobedience and of how to manage wayward youths.

JF: Why do we need to read Nobody’s Boy and His Pals?

HH: First of all, it tells a good story. But also it suggests an alternative understanding of the “boy problem,” a pervasive anxiety that is with us today, still. Reformers in the Progressive Era thought the solution to the “boy problem” lay either in reforming poor and impoverished parents or in creating alternative institutions that would substitute for parents, but create a parent-like environment. By contrast, the BBR was a site where adolescents governed themselves, democratically, for the most part with little or no adult supervision. That belief in self- government and in what I characterize as a faith in the power of “pals,” may be something useful to learn from Robbins and the BBR.

The book also illuminates an early 20th century radical or “Progressive” democratic culture that has not had the attention it deserves.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

HH: I became an American historian after going to law school, out of a complex sense that legal education was missing something important about what law did in American society. And then I discovered that I loved reading legal texts with a historian’s eye and sensibility.

JF: What is your next project?

HH: I want to return to the property law project that I began back in 2019. My focus now is on the ways that most all Americans have experienced property law as “trespassers” on lands belonging to others. Trespass is as important as “possession.” I mean to explore the relationships between the property law that has been taught in law schools over the past 80 years, since World War II, and our daily experiences of “property.” I am particularly interested in what property law has meant in moments of crisis and social conflict, as in the pandemic and other recent events.

JF: Thanks, Hendrik!