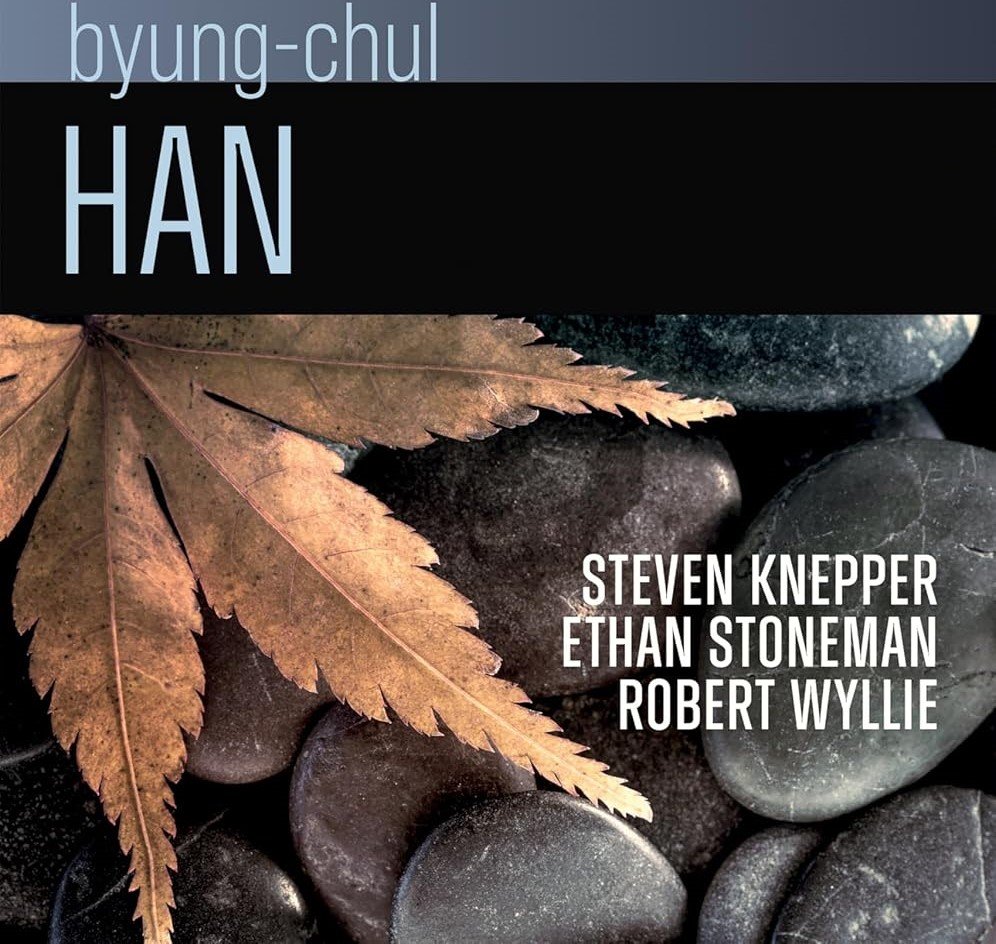

Today’s interview is a little bit unusual, as it is a conversation with three scholars. Steven Knepper is Bruce C. Gottwald, Jr. ’81 Chair for Academic Excellence at Virginia Military Institute. Ethan Stoneman is Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Media at Hillsdale College. Robert Wyllie is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Ashland University. A triumvirate that wields its power for good (an obligatory Roman history joke), they are the co-authors of a new book, Byung-Chul Han: A Critical Introduction, out today with Polity Press.

***

Nadya Williams: Many thanks to the three of you for agreeing to this interview and congratulations on your book’s release! I have been hearing Byung-Chul Han’s name here and there quite a bit recently–for instance, The New Yorker published an in-depth profile piece about him this April, calling him “The Internet’s New Favorite Philosopher.” This bold description seems ironic, since the blurb for your book describes him as “renowned for his critiques of our digital age,” and this is indeed the context in which I have heard his name mentioned most. Still, he is an enigma for most of our readers (or so I think), so maybe, let’s start there. Who is he? Why does he fascinate each of you? In what ways is he different from other people who have been arguing against the digital age and in defense of human flourishing (e.g., Wendell Berry)?

Robert Wyllie: Byung-Chul Han is certainly a sharp critic of the people we become as we become more digitally connected to everyone else. Perhaps we feel lonely and burned out and turn to Han, or perhaps, as you suggest, Internet users who appreciate Han are self-loathing or ironic.

Steven Knepper: Han’s critique of the Internet is about as pessimistic as they come. He claims that digital devices entice us to click-and-click-and-click, to binge-watch streaming services, to continually turn from the real world and real human relations to narcissistic digital resonance chambers. We ultimately burn out or fall into an existential malaise. We think we are simply pursuing our interests or goals or “taking care of business” online, but we are overdoing it to the point of self-destruction. Since we harm ourselves, Han calls this “positive violence.” Of course, as Han points out in books like In the Swarm and Infocracy, tech companies facilitate this through addictive design and algorithms. (I am pessimistic myself, but I think Han overstates things. He leaves little space for real relationships to develop online.)

Ethan Stoneman: My main area of expertise is media and cultural studies, so I came to Han through his first book-length study of digital media, In the Swarm. In that work, he articulates his project with the tradition of media theory and media ecology, specifically through the figure of Marshall McLuhan. Basically, this means that Han approaches questions of the digital through a technological lens, focusing on how digital media condition underlying psychic and social order, rather than texts, ideas, or anything captured by the theorems of social science.

Han’s prognosis for our increasingly digital society is rather bleak, as Steve indicates above. What I find most interesting about Han is not his techno-pessimism (though I find it refreshing) but the dominant tendencies he identifies in our digital infosphere, namely, positivity and transparency. In this context, positivity refers to the erasure of negativity—of distance and difference—and its replacement with “the same”.

Transparency is Han’s name for the technologically realized social imperative that everything must be visible, open, ready, and available for everyone at all times. Together, transparency and positivity coax everything and everyone out into the smooth, open flows of capital, communication, and information. I think these are the two major concepts he contributes to media studies. In my experience, students get a lot of mileage out of applying them in their own analyses.

RW: Unlike Nicholas Carr (“Is Google Making Us Stupid?”) or Shoshana Zuboff (The Age of Surveillance Capitalism), Han is coming out of a German philosophical tradition that thinks abstractly and often dialectically about power. So his central insight in The Burnout Society is that self-exploitation is everywhere replacing exploitation-by-others.

The living tradition of German philosophy that Han is carrying forward has always been holistic and close to art. When Han writes about the mental health crisis and social media—my students’ very real problems—it is in ongoing conversation with Hegel and Heidegger, composers and novelists. These conversations get to the heart of things that young people are thinking about. So for a teacher, especially anyone tasked with teaching modern German philosophy to American undergraduates, he fascinates.

SK: In addition to the critique of burnout, Han offers a hopeful remedy to our digital sickness. He calls for a renewal of ancient contemplative practices, for renewed real-world relationships. Here, and especially in more explicitly ecological recent works like Vita Contemplativa, his concerns converge with those of someone like Wendell Berry. Still, Han is a philosopher of the city rather than of the countryside. You see this in Isabella Gresser’s documentary from 2015, The Burnout Society—Byung-Chul Han in Seoul/Berlin, available on YouTube, which moves through these two cities and their relationship to his life and thought. I recognized Han’s diagnosis in some of my own struggles with screens, but the contemplative Han really drew me in, especially in books like The Scent of Time and Saving Beauty.

NW: What do you hope to achieve with this book, and why do you think it is needed now?

RW: This is the first book on Han in English and the first comprehensive study of Han’s thought in any language. Han has written more than one short book per year since 1996; this year he released his thirty-first book, The Spirit of Hope. So, it is time.

Appreciation for Han is growing among scholars, writers, and the general public. But there is a danger of misunderstanding Han if you only read his short polemical interventions on this or that topic, like his famous claim in The Burnout Society about the obsolescence of repression in our dawning age of self-exploitation. If we are successful, Byung-Chul Han: A Critical Introduction will help these readers understand the continuities and nuances of his thinking across his many books and the many academic fields they cross.

SK: We explain Han’s ideas in clear language with lively examples from popular culture (novels like Samanta Schweblin’s Little Eyes, shows like Black Mirror and Squid Game, movies like Office Space). In that regard, our book should allow anyone who is interested to get a better understanding of Han’s key ideas and, as Rob suggests, the big picture of his philosophy. But we also situate Han’s arguments within several disciplines and make our own Han-inspired interventions in, say, democratic theory or aesthetics that will hopefully stimulate scholarly discussion of Han.

ES: I don’t have much to add here that Rob and Steve haven’t covered. The one thing I’ll say is that with intellectuals who strike a chord with educated nonspecialists, there is a tendency with academia (fueled in some cases, no doubt, by resentment) to dismiss that thinker’s popularity as unserious, merely a fad. I’m thinking, in particular, of Jean Baudrillard and Slavoj Žižek. I hope that as this delegitimizing discourse begins to crop up around Han—and, on social media, it already has—that our book will, to some extent, act as a countermeasure and provide a more critically appreciative and charitable account of Han’s ideas

NW: If someone wanted to dip a toe into Byung-Chul Han’s oeuvre, obviously your book is meant to be a great starting point. But is there anything else you would recommend? Any related thinkers you think should be read alongside him?

RW: Our critical introduction is meant, in part, to suggest different starting points in Han depending on the reader’s interests and questions. Recently Steve and I finished a forthcoming piece for The Philosopher, a public philosophy magazine in the UK, that suggests five different ways to read Han. In that essay, we point to Han’s book on globalization, Hyperculture, as a way to grasp his own self-understanding as a Korean-German philosopher.

Back in 2017, I started with The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering, which is fascinating, strange, and remains one of my favorite Han books. Ethan recommended Han to Steve, and Steve came out to visit me at Notre Dame and handed a copy of Scent of Time to me. It is about fragmented modern time-consciousness, how time “whizzes by” for us because we lack liturgies and seasons to share time with others and the earth.

ES: My intellectual horizons are probably narrower than Rob’s or Steve’s. My recommendations are all works that have secretly or not-so-secretly informed Han’s thinking about media and technology or would provide a useful supplement. In the first place would be Jacques Ellul’s 1954 classic The Technological Society. It brilliantly and systematically lays out the role of “technique” in clarifying, arranging, rationalizing, and bringing efficiency to everything. (By “technique,” Ellul means machinery and other technologies, as well as methods for organizing human activity in ways that maximize the ratio of output to input.)

SK: I really like Han’s recent book Non-things. It sums up and expands Han’s arguments about digital “non-things,” such as smartphones, which destabilize life and constantly surveil you. It defends old-school “things” that stabilize your life over time. One of his interlocutors is Matthew Crawford, the author of Shop Class as Soulcraft and The World Beyond Your Head who is probably familiar to many of your readers. There are great riffs on physical books and the uncanniness of old houses, and Han ends with a lyrical chapter about the jukebox he keeps in his Berlin apartment alongside his grand piano.

ES: I’m convinced Han had this on the brain when writing Non-Things, which is probably my favorite of Han’s books as well. In general, Flusser is one of Han’s more interesting interlocutors, if only because of how they align and depart from one another. In particular, I’m thinking of Vilém Flusser’s The Shape of Things: A Philosophy of Design (1993). I can’t think of another figure who is simultaneously more alike and different from Han.

A third thinker I’d recommend would be Harold Innis, and especially The Bias of Communication (1951). Like Han, Innis offers us what could be characterized as a non-Marxist critical theory. Two of his juiciest ideas are that media are a means of concentrating force over people and nature and that each new medium breeds a new monopoly of knowledge—i.e., a cadre of specialists who figure out how to manipulate and program that medium’s special carrying capacities and standards.

RW: One related book that everyone should read is Antón Barba-Kay’s A Web of Our Own Making: The Nature of Digital Formations, which is about how the Internet is ruining our capacities to think about politics especially.

NW: All three of you are academics, and here we are, about to start another academic year, and I keep hearing all kinds of grim predictions about how it’s all going to go down in the age of ever-expanding AI. What are your thoughts? And what would Byung-Chul Han say (or has said) about these most recent advancements?

RW: AI will be integrated, inevitably, into research and teaching. But Han does not think this is a salutary development. Han opens his book Infocracy by warning that we are “communicating ourselves to death” by reducing the world to data, facts, and information. And we are communicating ourselves as long as the search algorithms and AI bring up precisely the worlds of facts that we were searching for in advance.

I suggest in the book that we are probably bigger believers in liberal education than Han is, for all sorts of reasons, but we need to make the case in our classes that learning is more than assimilating information, and make sure our classrooms are places where the challenge and strangeness of other ways of life are present.

ES: I agree with Rob. I think one of the ways we can strengthen liberal learning at this juncture is to reinvest more seriously in the slowness and messiness of orality and to stop fetishizing that ossified “assessment tool” called the college essay—which, by the way, did not originate with liberal arts colleges but, ironically, in the nineteenth-century German research university, specifically, the Humboldtian model of higher education. That’s not to say that we should no longer cultivate strong writing skills in our students, but AI presents us with an “opportunity” to figure out what kinds, forms, and practices of writing we will require and why.

SK: Only God can save us. In the meantime, we need to make the case to students, administrators, and the public that students need strong writing skills even to work with AI successfully. Ethan and I may need to duke this one out.

NW: What larger questions fascinate each of you in your reading, thinking, and writing?

ES: I began my academic career writing mostly in the history, theory, and criticism of rhetoric. I haven’t abandoned the study of rhetoric, but over the last seven years, I have devoted more and more of my thought to questions about media and technology.

I’m currently wrapping up a co-authored book project titled Vital Signs: Cultural Techniques of the Undead. This manuscript, which is grounded in continental media theory, examines how technology allows us to manipulate the boundaries between life, non-life, and the “undead.” Once this boundary is revealed, vitality then becomes a site of experimentation—conscious life becomes something to be bypassed (in the case of anesthesia or mind control), suppressed to its barest margins (in the case of cryonics), or pushed to its maximum vitality (in the case of bioastronautics). An article laying out some of the book’s theoretical foundations (and drawing on Han) recently appeared in the cultural studies journal Theory, Culture, & Society.

SK: My scholarship moves between literature, philosophy, and religion. I am also a poet and recently started a literary journal and newsletter titled New Verse Review. These may seem like very wide-ranging interests, but what unifies them is an abiding interest in—or better, pursuit of—contemplation and wonder. Han has taught me a lot about those and especially about how the digital can stymie them, but my great guide has been the contemporary Irish philosopher William Desmond, the subject of my 2022 book Wonder Strikes: Approaching Aesthetics and Literature with William Desmond.

RW: I am writing a larger book project on envy in the history of political philosophy. I am broadly interested in how painful or negative emotions might support the societies we wish to live in, like the constant paranoid tyrannophobia that is Montesquieu’s price of living in a free society, or the way envy seems to support equality and distributive justice for a whole range of thinkers, like Aristotle or Søren Kierkegaard, to name the two companions who tend to provoke me most.

When you’re already primed to worry that living in a free society never makes you really feel free, Han’s argument in The Burnout Society that the initial thrill of liberation suckers you into addictive and self-exploitative personal projects really hits the mark. It makes you wonder if, as Han says, we have learned to exploit freedom itself.

Fascinating, thanks for publishing this!