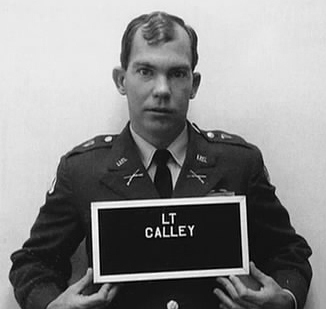

We learned yesterday–at the end of July–that Lt. William Calley, aged 80, died back in April. That lag indicates that his wish that he could “sink into anonymity” was close to becoming reality. But, here we are reading about him, as he surely knew we would.

The man was close to being a cipher, one of the many pale figures any society throws up by necessity–as we can’t all be extraordinary–and Calley was about as unextraordinary as any, until his actions on a single March morning in 1968 elevated him into the pantheon of lesser celebrities.

His celebrity was not the kind anyone would wish for. If you know the details of the My Lai massacre you surely don’t need to hear them again; if you don’t, you need more than this blog post to appreciate their enormity. (There’s a lot of ways into it but maybe this is the most convenient.)

And the actual crime is only the half of it, as tragic and near-perverse as that is to say. My Lai was central to the blackened image the US Army bore coming out of Vietnam (and generated some serious soul-searching in the institution, too). The president was dragged into the controversy over whether Calley should be held responsible for his actions (78% of Americans believed he shouldn’t be), and did not acquit himself well.

The murders that morning half a world away, and the trial in Georgia several years later (after a cover-up failed when citizens took it on themselves to get it to the nation’s attention, first by contacting legislators–who did nothing–and finally by enlisting the press, which succeeded) led to a debate that raged in the news weeklies and across kitchen tables for months. It was raucous and rancorous, and contributed mightily, in the end, to the exhaustion everyone felt about the war by 1972. It undoubtedly enhanced Nixon’s sense that the war simply had to be ended for the sake of the nation’s sanity.

It’s too bad the event–and the debate that followed–isn’t taught more outside of military settings. It’s a crash course in the tragic ambiguities of war. Even granting–as we should–that Calley was morally obligated to refuse such an obviously immoral order (to exterminate the Vietnamese population of the area is how he understood it), so much remains to poleax the investigator. How did a 24-year-old community college drop-out (he’d worked as a bellhop and dishwasher) who had once been rejected by the Army come to be in such a position of responsibility in the first place?

We know how, actually: the military was burning through manpower at a terrific pace in Vietnam and was desperate for recruits. The Army was plagued with difficulties, from staffing to training to the demoralizing effect of being saddled with an unwinnable war. The institution itself was becoming dysfunctional in many ways. And then there are all the specific realities of that war as experienced by Charlie Company in the days leading up to the massacre–the booby-traps, the sniper fire, the casualties–all of which can lead the reader right up to the edge of sympathy with the claim that there is no law in war until you remember all the other soldiers who experienced the very same war in all its terror and confusion and didn’t commit mass murder as a result.

It’s of the nature of where our attention fixates that William Calley’s name is so well-known, but Hugh Thompson’s is not. Thompson and his helicopter crew were responsible for saving the lives of many Vietnamese that morning, at great risk to themselves (they actually leveled their weapons at other uniformed Americans who were following orders, risking a firefight or a lifetime in prison). His refusal to keep quiet actually put a stop to the massacre. A summary of his actions that day:

During the massacre, Thompson and his Hiller OH-23 Raven crew, Andreotta and Colburn, stopped a number of killings by threatening and blocking American officers and enlisted soldiers of Company C, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division. Additionally, Thompson and his crew saved a number of Vietnamese civilians by personally escorting them away from advancing United States Army ground units and assuring their evacuation by air. Thompson reported the atrocities by radio several times while at Sơn Mỹ. Although these reports reached Task Force Barker operational headquarters, nothing was done to stop the massacre. After evacuating a child to a Quảng Ngãi hospital, Thompson angrily reported to his superiors at Task Force Barker headquarters that a massacre was occurring at Sơn Mỹ. Immediately following Thompson’s report, Lieutenant Colonel Frank A. Barker ordered all ground units in Sơn Mỹ to cease search and destroy operations in the village.

But Thompson–who died in 2006–deserves more recognition than that. He was not an ethicist, though he eventually–after years of harassment for his role in exposing My Lai–was featured as a speaker before numerous audiences of officers in training at the military academies. His lessons were simple in the extreme: Listen to your heart. Do what you know is right. Don’t succumb to peer pressure. Where he was extraordinary was in his courage. You can’t do better than to read his own reminiscences of what occurred on that March morning in 1968.

May his memory be for a blessing.