Olasky gives us America’s story through the lens of character, experience, and faith

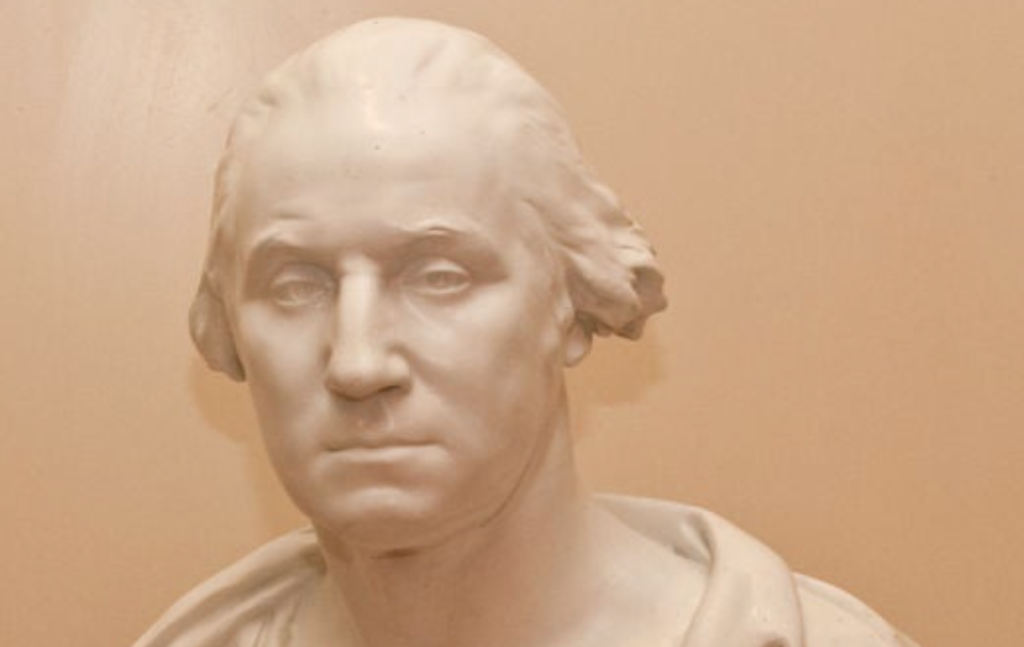

Moral Vision: Leadership from George Washington to Joe Biden by Marvin Olasky. Free Press, 2024. 464 pp., $19.99

“During the 1990s and the scandals of the Clinton administration, evangelical Christians were pretty certain that Bill Clinton was a living demonstration of the fact that character matters and that a lack of character can be fatal for leadership.”

So wrote Southern Baptist Theological Seminary president Al Mohler Jr. in June 2016, at a time when other leading evangelicals had decided to back another ambitious man known for marital infidelity and dishonesty. “If I were to support, much less endorse, Donald Trump for president,” continued Mohler, “I would actually have to go back and apologize to former President Bill Clinton.” Mohler insisted that personal character matters in political leaders, whether a Democrat in the late-twentieth century or a Republican in the early twenty-first. When the Access Hollywood tapes came out later that year, a horrified Mohler asked fellow believers, “Can we put up with someone and can we offer them our vote and support when we know that person not only sounds like what he presumes and presents as a playboy, but as a sexual predator?”

The answer, in the end, was yes. It took Mohler longer than most white evangelicals, but in 2020 he changed his position and supported Trump’s reelection.

Not every Christian conservative was willing to be so pragmatic—or hypocritical. Marvin Olasky, the longtime editor of World magazine, called Trump unfit for office in 2016—as he had deemed Clinton to be in 1998. Olasky resigned after Mohler was invited to launch World’s opinion newsletter in 2021. But he has continued his prolific career as a writer, publishing two books this election year: a memoir, Pivot Points, and a timely revision of his 1999 study of The American Leadership Tradition: Moral Vision from Washington to Clinton.

“From my selfish point of view,” Olasky told religion journalist Terry Mattingly in 2022, “the whole Trump era has been a vindication” of this book, originally inspired by Clinton’s scandals. While the update extends through Joe Biden’s presidency and adds nuance to a book that Olasky now agrees was “censorious,” the experience of recent years leaves him affirming with George Washington that “the foundation for national policy will be laid in the sure and immutable principles of private morality.”

Not that what’s now called Moral Vision is purely a work of moral philosophy. Olasky presents it first as “an introduction to American history.” Specifically, he offers a study of the past that would appeal to “anyone tired of today’s textbook tendencies to submerge the role of individuals as big economic and demographic waves roll in.” Against more deterministic approaches, Olasky insists on the agency of leaders whose personal stories can alter the arcs of larger narratives.

He generally does well to let his mini-biographies of great (and not-so-great) men and women reveal larger themes from political, economic, and social history. The new chapters on Ida B. Wells and the Trail of Tears, plus the expansions of several presidential profiles, demonstrate Olasky’s commitment—informed by his experience covering #MeToo and George Floyd—to pay closer attention to themes of gender and race in U.S. history. But his coverage is more idiosyncratic than what you’d find in other surveys of U.S. history, since he uses the past primarily as a guide to the future. He wants to “help voters sort through [presidential] candidates in 2024 and beyond by measuring them against previous leaders.”

So how does Olasky advise Americans, whose choices this November are in flux even as I write this review? Should his fellow religious conservatives support a Republican Party that no longer seeks a national abortion ban? Should progressives insist on a replacement for President Biden who is less willing to back Israel’s war in Gaza? Rather than approaching our vote as a transaction calculated to advance whatever policy ends matter most by whatever political means are necessary, Olasky recommends that we place at the center “moral vision, which is the sum of character, experience, and faith.”

First, faith. On the one hand, Harry Truman’s dependence on bedrock biblical ethics helped him “advance in a world of corruption and remain ‘reasonably pure,’” just as Teddy Roosevelt had earlier “insisted on clear and concrete applications of biblical commandments.” On the other hand, the Presbyterian elder Woodrow Wilson decided that he “could redefine morality to his own liking, substitute his own thought for God’s, and believe himself to be infallible.” So far as FDR goes, attending Episcopal services “had little effect on Roosevelt because he relied on his own feelings rather than the Bible.” We should certainly pay attention to the complicated relationship between religion and politics in a country that separates church and state, but readers looking for more sophisticated analysis should consult the installments on Teddy Roosevelt and Wilson in Oxford’s Spiritual Lives series or the volume on FDR in Eerdmans’ Library of Religious Biographies.

Also from the latter series, look for Daniel Silliman’s forthcoming biography of Richard Nixon—whose absence from Olasky’s roster is disappointing. Rather than devote space to the stories of John D. Rockefeller, Booker T. Washington, and other non-presidents who never faced the moral challenges unique to the world’s most powerful public office, I would rather have read Olasky testing his argument about moral vision on Nixon. Raised as a Quaker and an inconsistent churchgoer as an adult, Nixon became a remarkably determined, accomplished, and skillful politician whom Silliman describes as “amoral, driven by ambition and resentment, his actions moderated only by his shame.”

Second, experience. Specifically, Olasky emphasizes stories of leaders “overcoming hardships,” such FDR’s battle with polio, which “built his character” just in time for the Great Depression, when “America needed someone who could go whistling by the graveyard, saying confidently, against the statistics, that all we had to fear was fear itself.” It’s also crucial that would-be presidents have a track record of “resisting the temptations that great power or great wealth bring,” since the safety of our republic depends now, as in Washington’s time, on “the self-restraint of those in power.” Truman, for example, developed the “balance and character to walk the tightrope of public service in a democracy” by serving with integrity and independence despite coming to office via the Kansas City political machine of Jim Pendergast.

Finally, character, which can be shown by “self-discipline under duress” but that Olasky primarily finds revealed in marital fidelity. He admits that his original book “sometimes fixated too much on” Bill Clinton’s most famous failing, and he recognizes that presidents as reckless with their vows as FDR and JFK have nonetheless behaved prudently and courageously in moments of global crisis.

Nevertheless, Olasky continues to criticize faithless men across the political spectrum whose extramarital affairs raise two other red flags: a disregard for the truth and a willingness to abuse power. (Clinton now shares a chapter with Newt Gingrich, who “was engaged in his own adultery while complaining about Clinton’s”—both affairs involving political underlings.) By contrast, few leaders come off better in Olasky’s judgment than the newly added Truman, who “owed his moral authority largely to the public sense of his honesty and faithfulness”—which mirrored his private commitment across more than fifty years of marriage. Olasky twice quotes Truman’s maxim that “a man not honorable in his marital relations is not usually honorable in any other,” and suggests a corollary: “A man honorable in his marital relations is not necessarily successful and not necessarily wise, but less likely to be destructive.”

Which brings us back to Donald Trump, recently convicted of a felony for paying hush money to cover up an affair with a porn star.

Olasky doesn’t single out the twice-divorced, three-time Republican nominee. Apart from two passing references to his conspicuous visit to a Washington church during the George Floyd protests, Trump doesn’t even show up until the last fifty pages. Even there, Olasky pairs Trump with Biden, offering criticism of both men, and paints Trump more as the beneficiary than the builder of a political culture that increasingly downgrades character.

But in the end, how Americans view their forty-fifth president will probably determine their opinion of Moral Vision. Olasky’s argument will reassure Trump’s opponents that they’re right to worry about the prospect of so immoral a man again holding so much power. But if someone’s already prepared to cast their ballot for a candidate who too rarely lets marriage vows, penitent faith, self-discipline, or constitutional norms restrain his destructive impulses, I’m not sure Olasky’s high-minded case for character will change their mind.

“Given our human psychology that rebels against cognitive dissonance,” Olasky concedes, otherwise scrupulous voters who have already held their nose once or twice before may “eventually believe the smell isn’t so bad.”

Christopher Gehrz is professor of history at Bethel University in St. Paul, Minnesota. His most recent book is a spiritual biography of Charles Lindbergh, and he writes about Christianity, history, and higher education at Substack.