Earlier this year, a small almond-shaped lead bullet, probably originally fired from a slingshot, was excavated in Spain. Still visible on it are the two names that were etched in when it was minted: CAESAR and IPSCA. The first of these gives us clues for the date and context of when this was used: during Caesar’s Civil War with Pompey, in which much of Spain took the latter’s side. But not this town, previously unknown to modern historians—for that is likely what Ipsca was.

Such inscribed bullets, found throughout antiquity, often had demoralizing messages and insults—“catch!” or “ouch” or “take that!”—adding psychological warfare to the real damage that such an object could do to human bodies when fired by an expert shot from a long distance.

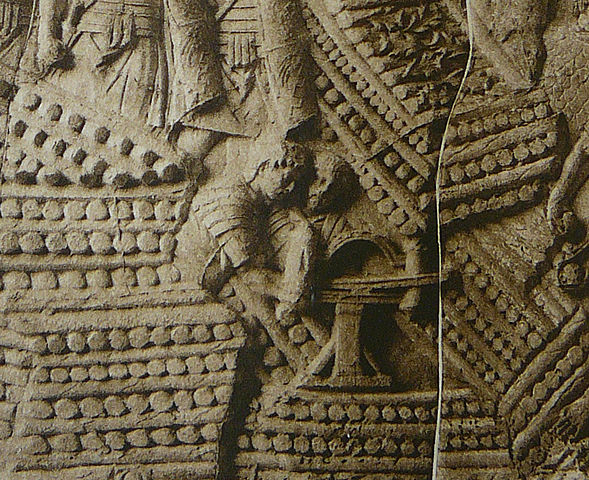

But most important of all, although slings and other projectiles could certainly be used on the battlefield, their use, especially following the invention of the catapult ca. 399 BC, revolutionized ancient warfare by making it clear to civilians that even within their city-walls, at home, they were not safe from attack.

I’ve had occasion to think about these inscribed bullets, the damage they did to the bodies of real people so long ago, as I learned about the deadly and unprovoked recent drone attack on Tel Aviv by the Houthis, a Yemeni rebel group, followed this past week by a deadly and likewise unprovoked Hezbollah attack. In the latter, a rocket shot from Lebanon killed twelve children on a soccer field.

These deliberate attacks on civilians–the latter during the Olympics, no less!–come in the same spirit of psychological warfare, aiming to tell people: you are not safe. We can get you. But the issues that emerge from this attack are much more timeless. They involve the question of the sources of justice when confronting injustice in war.

We think of the Geneva Conventions, which codify modern international humanitarian law, as something very modern. But these laws, so many of them focusing on reducing the impact of war on civilians—the weak, the vulnerable, those not serving in the military—were matters that residents of antiquity already puzzled over a great deal.

Hesitancy over brutalizing civilians is visible in the Homeric epics, even as this hesitancy, of course, did not prevent fairly extreme violence against civilians as a regular military tactic. Later on, over the course of the Peloponnesian War in the late fifth century BC, we see all decency and moral restraint disappear, as both Athenians and Spartans target civilians in cities allied with the opposing side. Contemporary historians and observers, like Thucydides and Xenophon, shuddered.

And then we get to the fourth century, the age of the catapult. Living in the twenty-first century, we forget how deadly premodern projectiles would have been. In her book Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs, folklorist and historian Adrienne Mayor documents the myriad creative ways people in the ancient world relied on the natural world to create biological and chemical weapons and to shoot them over the walls into cities. Sure, such weapons could be used on the battlefield against military personnel. But more often, they were used to target civilians. Just as we see in Homer, we see repeated concerns in our later Greek and Roman sources about resorting to such warfare—not least because anyone who used it left themselves open to retaliation, as they knew well. And still, the violations of the perceived and generally recognized laws of war continued.

The targeting of civilians in wars today, therefore, of which the attacks during this latest round of warfare in Israel are only one example, brings to the fore this question: what do the Geneva Conventions even mean today, when (not if) no one enforces them?

Indeed, what were the consequences for Hamas of attacking Israel on October 7, 2023? It seems that because Israel chose to retaliate, the international outrage following the initial attack turned animosity, instead, against Israel itself, fueling increased antisemitism in the US and in Europe. In the meanwhile, several dozen more civilian hostages—women, children, the elderly—still remain in Gaza ten months after capture, even as scores of them have also perished in captivity. Announcements of deaths of hostages in captivity now outnumber news of rescue.

Is this what international humanitarian law looks like? When humanitarian laws are only mentioned when condemning the violence against one group of civilians (the residents of Gaza) while encouraging further atrocities against another (the Israelis), the laws have failed. The moral basis for the laws, which aimed to promulgate in secular terms the theological truth about the preciousness of all image bearers, has been eroded, compromised, twisted beyond any recognition of its original intent.

The Geneva Conventions are, it seems, dead. But then, were such international humanitarian laws ever enforceable? The second half of the twentieth century, following these laws’ passing, was filled with massacres, bloodshed, and unspeakable brutalities. We hear or read about these events, usually somewhere far away, in a place we need to look up on a map. We feel outrage over the sheer injustice of it all, we shake our heads, and we do the only thing we can: decry the injustices, even as we mourn that such talk is cheap.

The failure of modern secular international laws seems to prove, at the end, some key theological truths that no man-made rules can circumvent, no matter how hard they try. Yes, on the one hand, all human beings are made in God’s image. And yet, the fallen nature of humanity also means that human beings since time immemorial have been awfully prone to regard their own preciousness as sacred while disregarding that of others. It is only in light of the fall that we can begin to comprehend the brutal nature of warfare—ancient and modern—with its cruel attacks on civilians, along with other ethical violations. Those committing them recognize the unethical nature of their attacks, but find ways to justify them nonetheless–as Christopher Jones showed in his recent review of Rory Cox’s new book, Origins of the Just War.

I am not saying that we should give up altogether in the face of this present violence and darkness—horrific and unethical attacks on civilians in Israel, in Gaza (yes, there too), in Ukraine, and many more places around the world. But I am saying that perhaps we should place less trust in the strength of earthly laws to solve problems of fallenness. The utter failure of the Geneva Conventions, now on display so obviously in Israel, in Gaza, and in Ukraine (to name just a few examples), offer us no better conclusion.

But our very mourning and outrage over this violence against all civilians is right and is not to be taken for granted. We know that this is not right. But how? Earlier this year, I wrote in Christianity Today:

The ancient world was defined by its acceptance of pervasive violence. True, some ancients bemoaned this status quo, but they had no expectation that it would ever change.

So why are we not like this today? The answer, in a nutshell, is 2,000 years of Christianity. The change Christianity made in bringing compassion and mercy to a world that defaulted to cruelty is so complete that it is difficult for modern American Christians to fathom. We take our norms around violence for granted, but we shouldn’t. They are uniquely Christian—and uniquely worth preserving.

History shows that Christians have never perfectly lived our confessed belief in the imago Dei. A stumbling block for my Jewish mother, for example, has been that some professing Christians helped perpetrate the Holocaust—in her birthplace, Ukraine, Christians sometimes turned their Jewish neighbors over to the Nazis. We could also mention the Crusades and many other violent evils. Church history includes plenty of blood.

But history also shows the sheer horror of a world without the moral vocabulary to recognize those evils, without the influence of the imago Dei and the rest of the Christian worldview. It shows the horror of a world guided by Caesar, not Christ.

Well said.