Why is majoritarian appeal so tough to come by for Democrats and Republicans alike?

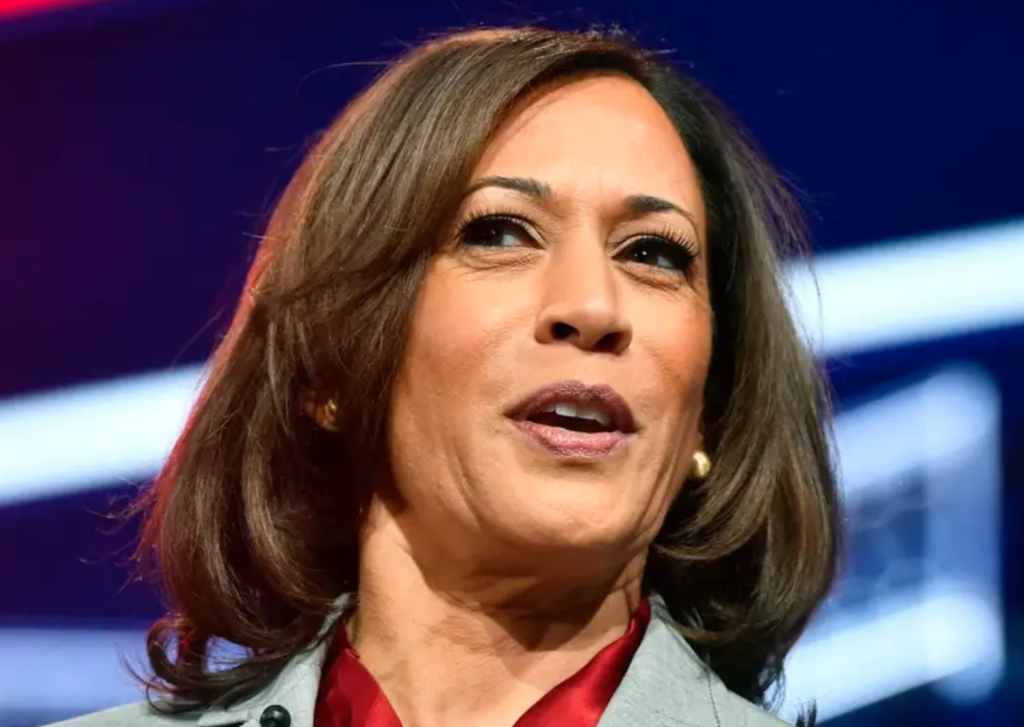

In the immediate aftermath of Joe Biden’s withdrawal from the presidential race, the Democratic Party elite has coalesced around Kamala Harris. It’s not hard to understand why. If the presidential race is about mobilizing one’s base—which has become the conventional wisdom of U.S. elections in this century—Harris is in a position to win and stabilize the Democrats as the nation’s governing party.

But there are serious problems with her candidacy. To some extent, they reflect the weakness of the candidate herself, but more generally they reflect the demographic weaknesses of the Democratic Party, issues it will have to address to succeed as the nation moves into the second half of the 2020s.

The first: geography. This is not always a major factor in national elections—the fact that Donald Trump hails from New York, for example, plays little role in his electoral prospects. He’s lost that state twice and will likely lose it again. But for most of American history, where a candidate is coming from really does matter. The fact that Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan were Californians was a consequential aspect of their political appeal, not only in terms of California being a large swing state at the time they ran but also because of the Golden State’s symbolic value in the nation as a whole. In the case of Bill Clinton, hailing from Arkansas was relatively minor in terms of its six electoral votes, but his origin as a son of the South was crucial for breaching what had become a red wall by 1992.

In 2024—as has been true in many elections since the mid-19th century—the industrial heartland is a key, maybe the key, to winning the presidency. It’s no accident that we’ve had eight presidents from Ohio. Harris is poorly positioned to prevail in the Old Northwest. She has no roots in the region, and there is little in her background to indicate that she has political strength there, whether as a matter of her positions (opposition to fracking, for example), or any demonstrated understanding of the issues of the white working-class voters who still comprise a majority of the population of Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. This is not an insuperable difficulty in terms of policy, but with the exception of abortion—an issue that Democrats may overplay in refusing to name any limits—she lacks regional appeal in addressing everyday realities of voters there.

Which brings us to Harris’s second challenge: identity. This term is typically interpreted as a matter of race and gender, and both are certainly considerations here, whether as a matter of genuine strength with key Democratic party constituencies or in view of the ongoing realities of racism and sexism. But the really operative identity in this context is Harris as the apotheosis of the meritocracy. Whatever its virtues, meritocracy is now and has long been unpopular in national life—political chickens are finally coming home to roost in rulings like the Supreme Court case Students for Fair Admissions. This is a significant challenge for any candidate who embraces meritocracy or is perceived to be a representative of it.

In theory, meritocracy—the notion that positions of authority in national life reflect demonstrated ability—should hardly be controversial. The problem is that there is now a widespread perception that meritocracy has become synonymous with elitism: just another means of professional-class rule rooted more in demographic markers than demonstrated talent.

Harris is not a perfect specimen of meritocracy. Although she is the daughter of two parents with doctorates, her educational pedigree is not Ivy League (except insofar as she is an alum of Howard University, sometimes called a “Black Ivy,” who has according to some benefited from passing the “brown paper bag test” of colorism). But she is without question a product of the San Francisco power elite, and her accession to the vice presidency was explicitly premised by Biden on the fact that she is a woman. And her positions on any number of issues (among them abortion and the Green New Deal) reflect the strong accent of the professional classes.

There has been a deep-seated suspicion of privilege in American politics since the time of Andrew Jackson, but gifted politicians like Clinton and Obama were able, through their own stories and skill, to finesse it. Yale Law graduate J.D. Vance is also a meritocrat, but he has disavowed that status; it remains to be seen whether he can get away with doing so—which he probably will have to if he’s to have a future in national politics. The Joe Bidens of the world (University of Delaware, class of 1965) have been the rule, not the exception, in winning the presidency in the last century. In this regard, Gretchen Whitmer, a graduate of Michigan State, is better qualified than Harris. Donald Trump’s single most important credential in the eyes of many voters is the loathing he engenders among meritocrats.

And then there is the matter of skill. Political talent comes in many forms and from many places. Joe Biden could not have lasted a half-century without it. Harris has strengths as well, notably a sense of charisma that serves her well, especially in smaller settings, though she may need to be careful about embracing her “brat” status while there are questions about her gravitas. She has in any case demonstrated personal deficiencies as a presidential candidate, whether in terms of managing her staff or in staking out incoherent policy positions.

In the 2020 campaign she attacked Joe Biden for a stance on school busing that she herself shared; she reversed herself on single-payer health care; and her positions on crime have zig-zagged between toughness and favoring leniency for Black Lives Matter rioters. There are some signs of more political assurance on the stump, her notorious word salads notwithstanding, but she remains largely untested in this campaign. Harris has been lionized for her prosecutorial zeal in querying figures like Brett Kavanaugh at his Supreme Court appointment hearings, but it’s a lot easier to question people from a pulpit of institutional authority than it is to get in a rhetorical fistfight with a dirty brawler like Trump.

Of course, like many vice presidents, Harris has been saddled with a thankless portfolio, particularly in terms of immigration. She has, reasonably, tried to emphasize root causes of the crisis, but she showed ineptitude in an infamous interview with Lester Holt. Fairly or not, she’s going to be weighed down by Biden’s baggage—probably the single biggest problem the Democrats have in 2024.

And that’s really the underlying problem here. Harris understandably wants to be president, and is a legitimate representative of many key Democratic positions and representatives of the party apparatus. But like the Republican Party before Trump’s successful hijacking of it, the Democrats are rotting from within, captured by constituencies that lack majoritarian appeal. This has become a problem in American politics generally: Extremes who control the primary process deprive voters of moderates with a real interest in coalitional governing. Biden’s withdrawal offered a way to break out this worrisome trend (as did his 2020 candidacy). But there is insufficient courage among Harris’s rivals to seize the opportunity.

If Harris loses, there will be a serious reckoning among Democrats, especially those who kept Biden’s weakness under wraps and then flocked to Harris’s banner. The party will then take stock the way it did after its three straight defeats in 1980, 1984, and 1988, and adjust accordingly. But many Democrats express fear that this may not be possible—since a second Trump presidency could mean the end of American democracy as we know it. If they really believe that, they should think twice before casting their lot with Harris.

Jim Cullen teaches history at Greenwich Country Day School in Greenwich Connecticut. His books include The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation and Bridge & Tunnel Boys: Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, and the Metropolitan Sound of the American Century.

Sheesh.

What a weak article.

I wonder what grievance spurred on the writer.

SIR: In the spirit of loving my neighbor, please do not reread this in the future.

Why do you think it is weak, Richard? Make an argument.

Not sure I understand your comment here Wingate.