Wonder, virtue, and more

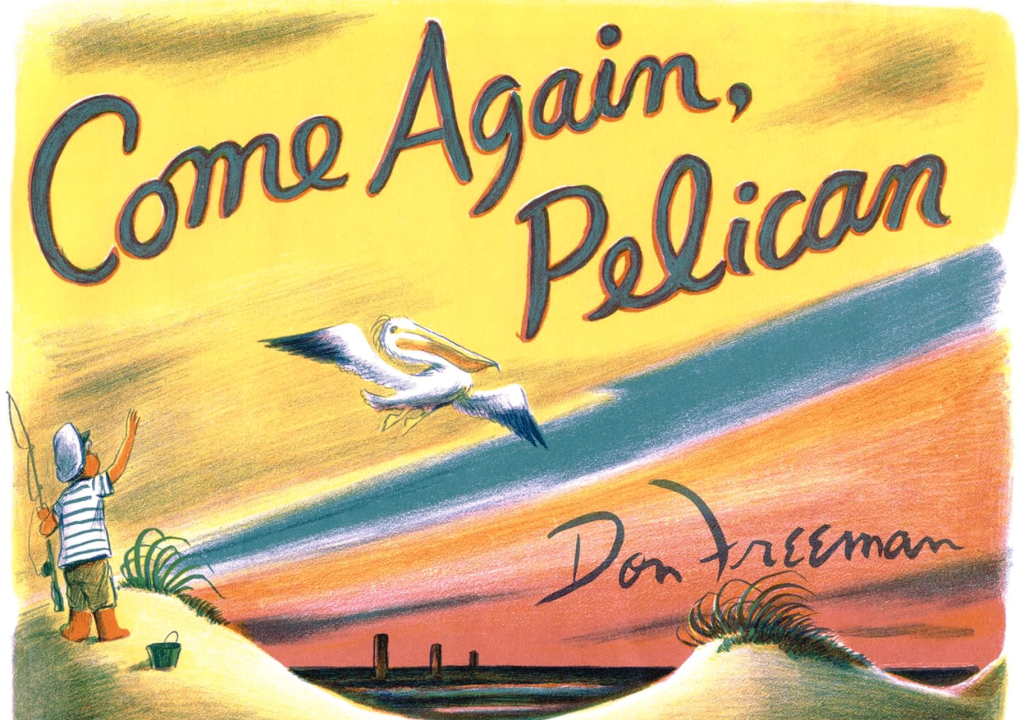

Come Again, Pelican by Don Freeman. Plough Books, 2024. 44 pp., $18.95

The sun rises. I feed the baby. If I’m lucky and he’s still tired, I put him back to sleep. I hear a voice from my toddler’s room. After getting dressed and pouring milk and saying a prayer and pushing the button on the coffeemaker, it’s time for the best part of my older son’s morning: as he says, “books!”

These early mornings spent with our books are not treasured by my son alone. Reading together has been one of my very favorite things about parenting. Sometimes, beset by crippling nausea in the early days of my second pregnancy, I felt guilty. Shouldn’t we be out identifying bird calls or driving to play dates instead of sitting on the couch with Eric Carle and Margaret Wise Brown?

Soon, however, he began asking for books by name and talking about their characters throughout the day. A love of books has marked my own life—as well as my husband’s—and I realized it was a wonderful gift to give to my own child.

When a beautiful copy of Come Again, Pelican by Don Freeman arrived in the mail, he was more excited than I was—and carried it off to begin reading immediately. When I finally had my own turn with the book, I was both delighted at Freeman’s illustrations and inspired to dwell on the place of children’s literature in our lives, even for those engaged in intellectually rigorous work.

Like many children, I grew up reading Don Freeman’s Corduroy, the tale of the loveable, green-overall-clad bear. Corduroy’s fame is inescapable; from mass-marketed stuffed animals to television shows to a spin-off series of board books, the bear has become a staple for American children.

However, it wasn’t until I heard of Plough Books’ recent reprinting of Come Again, Pelican that I became aware of the breadth of Freeman’s body of work. He won a Caldecott Honor in 1958 for his book Fly High, Fly Low; he illustrated a novel by Astrid Lindgren (of Pippi Longstocking fame); he co-authored several books with his wife Lydia. She was the better artist of the two, he claimed.

In Come Again, Pelican (originally published in 1961), Freeman tells the story of a little boy named Ty who goes to the beach with his parents and encounters the same bird he befriended on vacations past. The book is filled with page after page of gorgeous watercolor illustrations of rolling waves and colorful skies.

In 2024, many have become all too accustomed to children’s books—even picture books!—that have clear agendas. Maybe it’s a book that tackles a sobering moment in history, such as the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War. Maybe it’s a book that claims (humorously or otherwise) educational import, like Quantum Physics for Babies. Or maybe it’s a biographical treatment of a current political figure, whether on the right or on the left .

My family owns and enjoys many such books, so my intention is not to write them off. But sometimes it’s a breath of fresh air to read a book that understands the uncomplicated wonder of being a child. That’s what we found in Come Again, Pelican. Ty delights in his new red boots, in the thrill of catching his first fish, and in the majesty of the pelican’s flight. He learns, over the course of the story, about the comforting predictability of the natural world: about the ebb and flow of the tide, about the coming and going of the birds, about the symbiosis that we can achieve if we just take the time.

The value of children’s literature—whether simple picture books like Freeman’s or more complex tales for older children—is not evident to all readers, however. These stories are often considered a fitting subject for the interest of housewives, perhaps, or kindergarten teachers—but they’re far from within the purview of the intellectually serious.

Such an outlook is not merely unkind; it is deeply misguided. The “important” work that takes place within the halls of Congress, at elite academic institutions, on Wall Street: All of it has its roots in the humble activity of the home. The brightest minds solving today’s biggest problems were once children too.

A slew of recent books has addressed, from different angles, the national (and global) fertility crisis. In order to achieve population replacement, the women in most developed countries need to give birth to an average 2.1 children each. In the United States the fertility rate hovers well below this at 1.66. For those who grew up steeped in the faulty arguments of Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, this might not seem like much of a problem. People like Timothy Carney and Catherine Pakaluk think otherwise.

A society that has fewer children is one in which children’s interests have become increasingly niche. The myriad dangers of a declining fertility rate serve as the premise undergirding both Carney’s Family Unfriendly and Pakaluk’s Hannah’s Children. Both Carney and Pakaluk, however, argue that the fertility crisis cannot primarily be reversed through policy. First and foremost, it is a cultural crisis. In order to decide to make the radical life changes required by having children, a person has to see the life of a child as one of the world’s greatest goods.

Pronatalist intellectuals claim to do this. But in order to value children most fully, one must value more than just their conception and birth. One must learn to value the workings of a child’s life, simple though they may be. This includes, of course, children’s literature.

Like many of the young millennials Carney features in his book, I spend more time than I ought worrying about whether I’m a good parent. Flooded with information about supposed best practices, inundated with images cultivated by influencers, it is difficult to ever feel like I’m doing enough. But when I’m reading with my children, my mind slows.

Reading breaks through the chaos of dishes to wash and laundry to fold and diapers to change. Sarah Mackenzie writes about this in her book The Read-Aloud Family. As she puts it, the practice of reading together is about “going all-in for our kids . . . about doing what matters most with our time and energy today.” Our children “won’t forget how the hardest times of their childhood were eased by the sharing of stories, by the opportunity to leave the noisy, polluted city of life and stand for a time in the quiet of the garden with the people they love most of all.”

In addition to providing the opportunity for quality time, for the pursuit of a shared activity, reading with my children is one way in which I hope to prepare them for lives of virtue. Much ink has been spilled on the academic benefits of reading aloud to very small children. But what about the impact on their character?

Mackenzie considers this too: “If we tell them enough stories, they will have encountered hard questions and practiced living through so many trials, hardships, and unexpected situations that, God willing, they will have what they need to become the heroes of their own stories.”

Even now, I look back to the stories of my childhood in moments of decision or crisis or hardship. In the course of my daily tasks as a young homemaker, I cannot count the number of times I have thought about Little Women’s Meg Brooke (nee March) and her disastrous attempt to make currant jelly. As a recent college graduate, I was faced with the reality that my friends’ lives were changing at a different pace than my own. The friendship of L.M. Montgomery’s Anne Shirley and Diana Barry helped me to make sense of this and even to embrace it.

In his book After Virtue, philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre connects narrative and virtue, arguing that “[it] is because we all live out narratives in our lives and because we understand our own lives in terms of the narratives that we live out that the form of narrative is appropriate for understanding the actions of others.”

Furthermore, MacIntyre claims that “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’” By steeping our children in the words of stories, we are equipping them to answer these necessary questions.

We ought to care about children’s literature, regardless of whether we have young children ourselves, because books for children are doing the groundwork for shaping a society of virtuous men and women. The stories that children hear—and if they even hear them at all!—matter. We ought to celebrate the good ones.

When my young son listens to the words of Come Again, Pelican and soaks in Freeman’s beautiful illustrations, he is learning how actions have consequences, how people situate themselves in regard to the natural world, and how children relate to the instructions of adults—without my ever giving him a lecture about these things.

Freeman’s Ty, the little boy, waits patiently to catch his first fish, free from the constraints of adult supervision. His father warns him to be careful of the waves and to take care of his new boots, but also trusts him to spend the day alone on the beach. Freeman is clearly a writer who takes seriously the wonder and the inner lives of children.

When composing Corduroy, Freeman wrote to his wife about the project with excitement: “Frankly, I think it has more depth and feeling and simplicity than anything I’ve yet done.”

I hope I never become too grand or too important to let the simplicity of children’s books obscure from me their depth and feeling.

Abigail Wilkinson Miller writes from northern New York state, where she lives with her husband and sons. She holds an MTS in Moral Theology at the University of Notre Dame. Her writing can be found online at publications like Public Discourse and The European Conservative and at her Substack, Little House in the Adirondacks.