Contested nominations have been the norm, not the exception, in American history

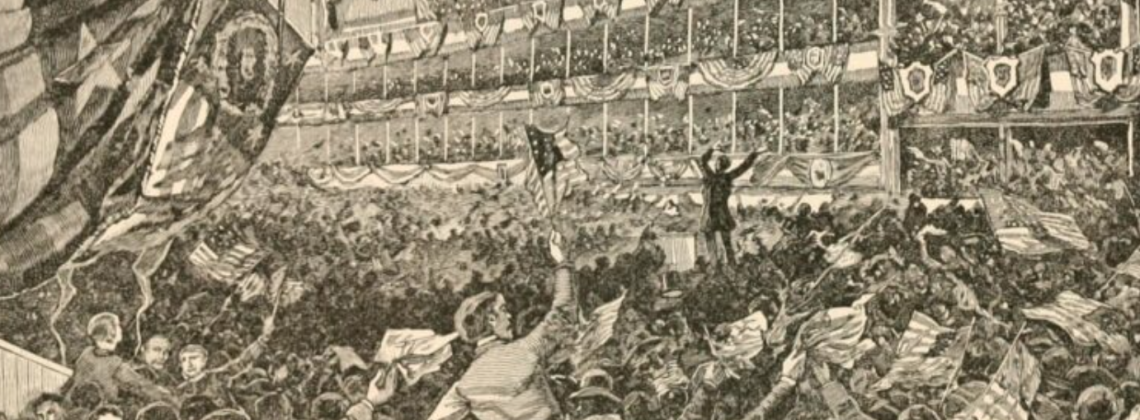

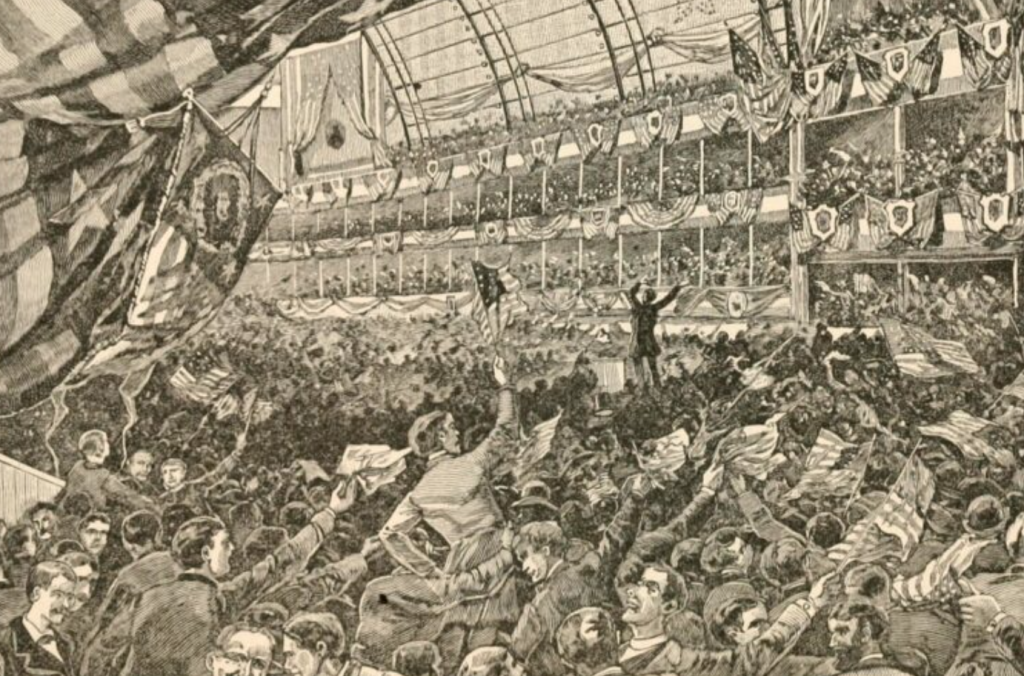

In the summer of 1924 the Democratic National Convention was held at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. The frontrunner for the nomination was William Gibbs McAdoo, the former Treasury Secretary and son-in-law of President Woodrow Wilson, and a prominent Progressive reformer. A Georgia native born during the Civil War, McAdoo had done well in primaries (fewer and less important than they are now), but he lacked the two-thirds of delegates necessary to secure the nomination. What McAdoo did have was the support of the Ku Klux Klan, which was then at the peak of its influence—North and South, Democratic and Republican, though the natural home of white supremacy since the Civil War had been the Democratic Party. There was only one Black participant at the convention. Women, recently enfranchised, were better represented.

McAdoo’s principal rival was Al Smith, the popular Irish Catholic governor of New York. His name was placed in nomination by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He famously dubbed Smith “the happy warrior” in what was FDR’s return to politics after suffering a crippling illness that would keep him in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Smith was representative of the diverse, urban forces rising in a party that had long been dominated by rural interests—he opposed the Klan as well as the newly ratified constitutional amendment prohibiting alcohol. He did not expect to win, and he didn’t. But he was able to check McAdoo, setting the stage for what became the longest nomination battle in American history. On July 9, after sixteen days packed in a hot building, the delegates finally gave the nod to West Virginian diplomat John Davis as a compromise candidate on the 103rd ballot. He lost the general election—as most expected he would—to Calvin Coolidge in a landslide. (Four years later, Smith got the nomination and lost to Herbert Hoover. The 1920s was not a good decade for Democrats.)

The Democratic National Convention of 1924 featured the longest nomination fight in U.S. history. But in the larger sweep of American politics it was typical in that it was not until the convention that a nomination was actually secured, after a bruising intra-party battle. In fact, it’s only been in the last half-century that conventions have become coronations, stage-managed spectacles meant to serve as political marketing. Contemporary observers often point to the Democratic nominating process of 1968 as the last contested battle, but the Republicans also had one in 1976, when an ascendant Ronald Reagan almost snatched the nomination from incumbent Gerald Ford in Kansas City. Ford lost to Jimmy Carter—the first product of the modern primary system. Reagan of course would knock off Carter four years later in what became a two-term presidency.

While highly contested conventions are often a sign of party weakness, this isn’t always the case. It took forty-six ballots for Woodrow Wilson to secure the Democratic nomination in 1912, and he went on to win two terms as president. Some of our worst presidents have been the products of this process (Franklin Pierce, Warren Harding) but it also produced Abraham Lincoln, a long shot who shrewdly positioned himself as an attractive second choice, and who emerged suddenly victorious on the third ballot in 1860.

In 2024 we face the prospect of the first non-buttoned-down contest in many people’s lifetimes. The Republican Party in effect experienced a bloodless coup in Donald Trump’s takeover of the GOP, which began in 2016 and was completed eight years later. The Democrats, as they so often do, look like they’re going to have a more public family quarrel. The nation’s political parties are less powerful than they once were, and this may be indicative of growing instability in the nation’s political system. For the first time in half a century we may be looking at a string of short presidencies. Let’s hope that this leads to a time of renewal for a body politic badly in need of it.

Jim Cullen teaches history at Greenwich Country Day School in Greenwich Connecticut. His books include The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation and Bridge & Tunnel Boys: Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, and the Metropolitan Sound of the American Century.