Some questions can only be put to rest with an affirmative answer.

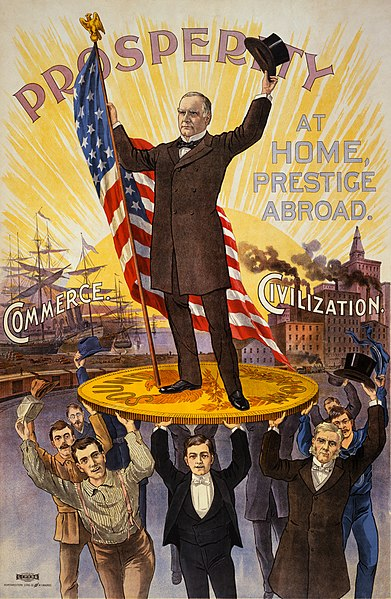

The United States experienced the worst economic depression of its history up till then in the mid-1890s. Unemployment, which had been at an admirable 4% in 1892, shot up to as high as 18% two years later. And in 1897 when the new Republican president, William McKinley was inaugurated, it still hovered close to 14%. McKinley stated the obvious in his inaugural speech: “The country is suffering from industrial disturbances from which speedy relief must be had.”

Not for the last time, however, a new president, eager to focus his attention on domestic matters, was hounded by unwanted questions of foreign policy. Ninety miles off America’s coast the Spanish possession of Cuba was aflame with rebellion. An independence movement was struggling to free its homeland from imperial control, and Spain was responding with force. American newspapers–newly adorned with the capacity to reprint actual photographs–kept the reading public abreast of Spanish atrocities. What was the responsibility of the US in this situation?

In the 1820s Secretary of State John Quincy Adams had assured Americans that we “go not abroad, monsters to destroy,” but that was then. By the 1890s the US was an economic powerhouse rivaling any in the world. Did not great responsibility come with this great power?

McKinley was far from eager to entangle the nation in a war, and he said so repeatedly. War meant a disruption of his plans and a distraction from his priorities. But with the lingering effects of the depression putting the midterm elections in jeopardy (and maybe his reelection in 1900 also), the question of whether America would be going to war was itself a distraction. McKinley’s assurance that it would not, might be overturned at any moment by events. As long as Cuba remained in turmoil, the question would dog the president, it might prolong economic uncertainty, and it could affect the election, too. McKinley finally put the question to rest by asking Congress for a declaration of war in April 1898.

Even as doubts have grown within his own party about his fitness to run, President Biden has insisted over the past several days that he’s going nowhere, that he’s in this election to win. His assurances are designed to put the questions about his age, his stamina, his effectiveness, to rest. Most of his supporters are on-balance pleased with his governance over the past four years, and many feel confident he might deliver a similar performance in a second term. They worry, of course, about how he would perform in a crisis. They worry also about his trajectory. The president’s debate performance was a shocking contrast with his State of the Union just four months earlier. Are we seeing a trend?

More worrying, of course, is how he will perform in the election. Even if his handlers can ensure he limits appearances to times when he’s at peak energy, even if he pulls them all off without a disaster, how will he be perceived? In any election, a candidate can’t afford to generate any cause for doubt. If the public is worried, you’ll need to be explaining, and when you’re explaining, you’re losing. The president’s rival for office has been remarkably disciplined since the June debate: as long as voters are asking about Biden’s fitness, Trump is benefitting. He’s making sure not to draw the spotlight to himself – a truly remarkable development, all things considered.

The Democrats are in a truly horrible position. With no obvious single alternative to the president waiting in the wings, with a maddeningly small window before the convention, and with a well-warranted fear of looking as if they are in disarray, most seem to believe they have no choice but to continue to back the president.

But the doubts about their candidate’s fitness can’t be wished away. As long as President Biden is in the race, voters will wonder if he’s going to change his mind at some point, or if events will render his determination moot. His supporters will still vote for him, but their worries about where the larger electorate will be in November can’t be dispelled. This appears to be one of those moments when only an affirmative answer can lay the question to rest.