Steve Teles, a political scientist at The Johns Hopkins University, writes: “The university’s ideological narrowing has advanced so far that even liberal institutionalists–faculty who believe universities should be places of intellectual pluralism and adhere to the traditional academic norms of merit and free inquiry–are in decline.”

Teles tries to explain why this is the case in a piece at The Chronicle of Higher Education titled “Why Are There So Few Conservative Professors?”:

A taste:

The point is that the perception of discrimination can have significant systemic effects, even in the absence of actual discrimination. If that is true, it has two implications for addressing the lack of conservatives in academe.

First, academic institutions seeking to create greater ideological balance among their faculty members would be wise to send visible, credible signals that they are not discriminating against conservatives. The more public these signals are, and the more costly they are to send, the more credible they will be. If academic leaders were to go to places where young, intellectually oriented conservatives are found (such as the numerous summer programs run by the American Enterprise Institute, the Hertog Foundation, Hudson Institute, and others) and make clear that their institutions want (indeed, need) them to be part of their intellectual community, that could make a difference. While academic leaders should not directly involve themselves in graduate admissions and training, it is wholly within their purview to ask their departments and schools to reach out to potential applicants who are likely to have right-leaning beliefs, and to ensure that their graduate-training culture is not ideologically exclusionary.

Second, if this model is correct, it suggests that conservatives themselves have an important role to play in addressing their own absence from academe. When conservatives complain — with some merit — about discrimination in higher education, they need to be aware that young people are listening. To some degree, the belief that the social sciences and humanities are profoundly discriminatory has become a feature of conservative identity. Even if that belief were true (and I think, in a simple sense, it is not), there are real costs to encouraging young people to believe it.

This presents a paradox, of course, since pointing too eagerly to the presence of discrimination can help reinforce the very dynamic that conservatives want to disrupt. That is why conservatives and academic leaders may need to move simultaneously, with academic leaders committing to costly, visible signals of openness and conservatives accepting those signals and amplifying them rather than receiving them skeptically.

Teles does not think the creation of separate conservative schools and programs on campuses is the way to go:

Given the low and dwindling number of conservative academics at a time when the number of conservative think-tank positions has surged, it appears that exit options work mainly to reduce conservatives’ incentives to play the academic game. However, new institutions emerging within academe may change this calculus.

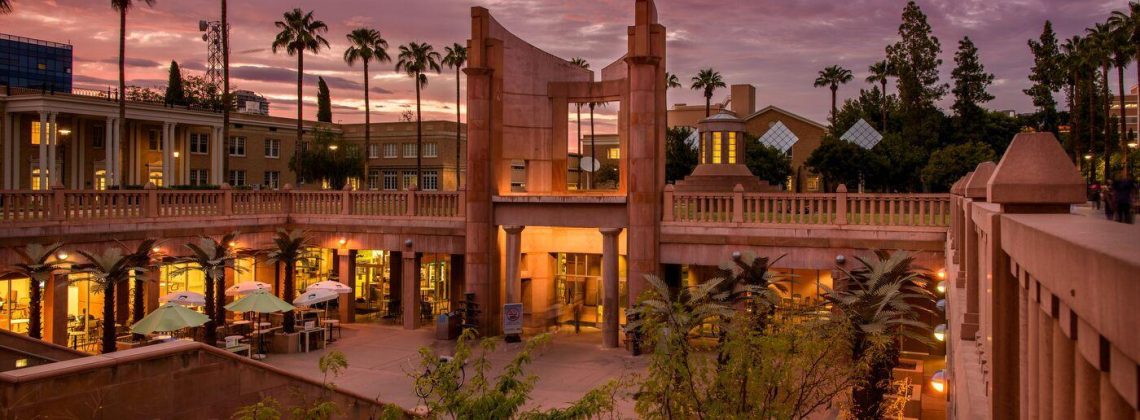

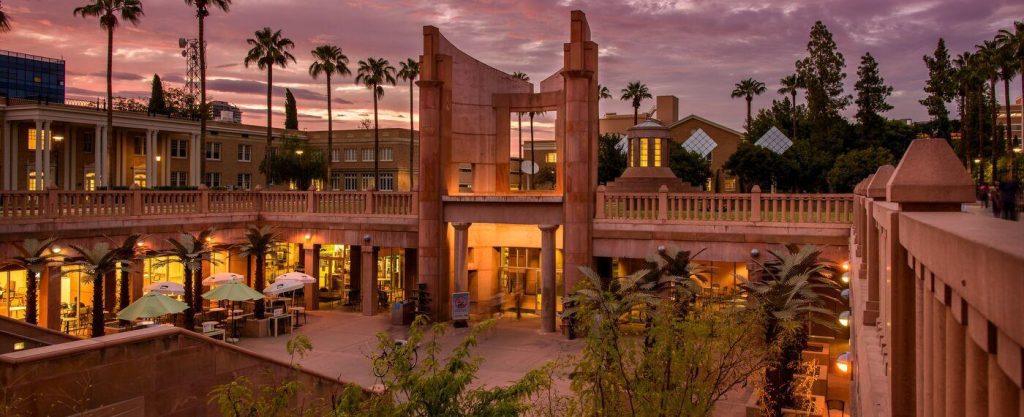

Public flagship universities in Republican-majority states are creating new schools — like the School of Civic Leadership at the University of Texas at Austin and the Hamilton Center at the University of Florida, both of which build on the original model of Arizona State University’s School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership — as fast as they can stand them up. These are a kind of exit option, at least from mainstream academe, that does not require leaving the university entirely to work within an ideologically hospitable institution.

The more such institutions are created, the greater the insurance policy conservatives have for attempting to enter academe. AEI’s Benjamin Storey and Jenna Silber Storey have recently argued that these new quasi-disciplines in academe will allow conservatives to circumvent the structural impediments in existing disciplines, to show that their approaches can generate scholarship that will receive recognition even from mainstream scholars, and to potentially create a pathway back into existing disciplines. If it worked for scholars of gender and race, whose work is now a recognized part of the humanities and social sciences, it could work for “civic studies.”

Perhaps. The risk they run, however, is that these new, conservative-friendly disciplines will produce academic ghettos rather than pathways into the mainstream. Conservatives may end up creating their own feeder institutions for Ph.D. recipients, their own journals that are not cited beyond the world of “civic thought,” and schools that are isolated within larger universities. In the process, creating a parallel conservative higher-education universe may simply reinforce the polarization of higher education by letting existing schools off the hook for finding a place for conservatives within existing disciplines.

Read the entire piece here.

Teles is responding to Jenna Silber Storey and Benjamin Storey’s Chronicle piece, “Will Republicans Save the Humanities?” Here is a taste of that piece:

For the first time in decades, certain parts of the long-suffering humanities are a growth sector in higher ed. Even more surprisingly, this expansion is being driven by state legislatures and governing boards dominated by Republicans.

At public colleges in red and purple states like Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah, about 200 tenure- and career-track faculty lines are being created in new academic units devoted to civic education, according to Paul Carrese, founding director of the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership (SCETL) at Arizona State University. These positions are being filled by faculty members trained in areas including political theory, history, philosophy, classics, and English. Since there are only about 2,000 jobs advertised in all those disciplines combined in a typical year, the creation of 200 new lines is a significant event.

Because a political party intensely critical of higher education has backed the founding of those programs, some worry that they will debase academic standards, subject intellectual life to political imperatives, and constrain teaching within certain ideological limits. Others hope that this burst of hiring might help colleges better prepare students for civic life and rebuild interest in the humanities.

Criticism of these new programs is both understandable and premature. Most of them have just been founded and have yet to demonstrate exactly how they intend to fulfill the mandates that have set them in motion. They have not had time to create a track record by which they might be judged, and they will each develop in different ways. For now, understanding the motivations of the faculty members who join them may be the best way to discern where those programs are headed. Who are the academics working in these programs? Why have they moved from other colleges? How do they think about their responsibility to the legislative mandates that created these projects? And how do they plan to build academic programs with integrity under intense and conflicting political pressures, from both on and off campus?

Read the rest here.

Just yesterday we got this from Kevin Roberts, the president of the Heritage Foundation, one of America’s leading conservative think tanks, reacting to SCOTUS’s decision on presidential immunity:

“We are in the process of the second American Revolution, which will remain bloodless if the left allows it to be.”

Insofar as this kind of thinking is either representative of current conservative attitudes (it largely is) or is unobjectionable to conservatives who wouldn’t say it out loud themselves (that’s everyone else), it illustrates how hard it is to integrate contemporary US conservative voices into the academy.