Give plain speech a chance

At the tail end of the 1960s and the early 1970s the American landscape was awash in countercultural artifacts. There were natural foods stores, with their creative calligraphy, rustic interiors, and exotic aromas. Women with wire-rimmed glasses and long hair and skirts floated about looking like they’d just emerged from the prairie. Psychedelically decorated VW buses were everywhere. Young families kept The Whole Earth Catalog around; more radical types might be reading Abbie Hoffman’s guide to living outside the law “in this prison that is Amerika,” Steal This Book.

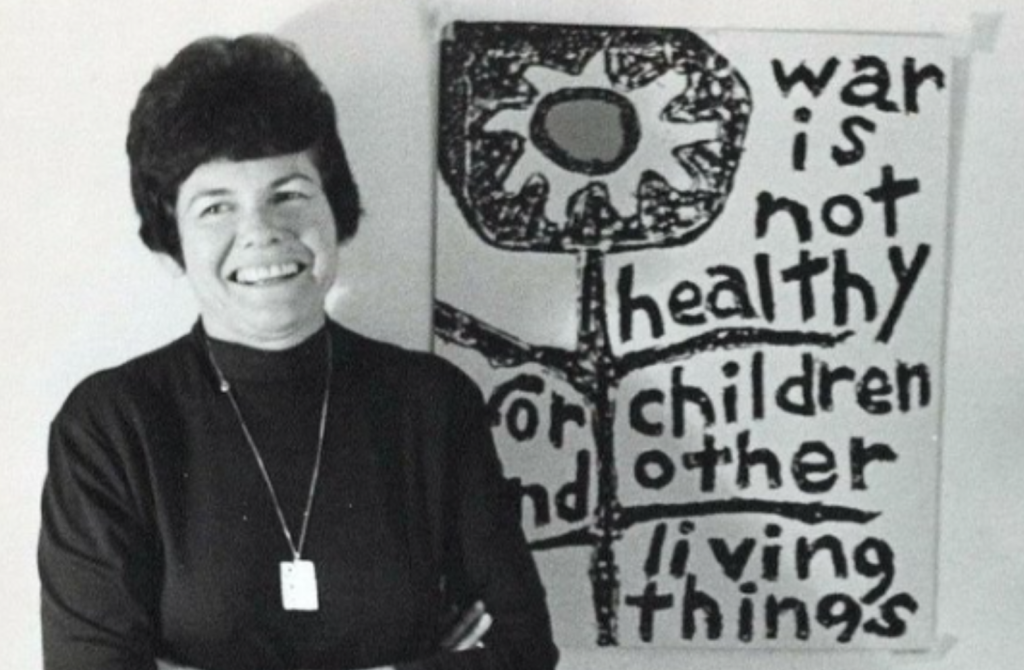

Everywhere—and by “everywhere” I mean everywhere—there was the poster. You saw it in the record store between images of Bob Dylan and Sitting Bull, at the coffee house above the wicker chair, at the health food store stuck to the cash register, in the kitchens of grad student apartments, and on buttons pinned to faded jean jackets. You might even see it at a Catholic church if it was the kind that offered folk masses. It was a simple yellow-and-gray rectangle, with one large flower and a phrase scrawled in neat but childlike lower case: “war is not healthy for children and other living things.”

In those days the culture moved fast. It seemed like light years had been traversed from the Beatles of 1965, with their unthreatening Edwardian jackets and their songs of puppy love, to the Beatles of 1967 and their shaggy beards, Maharishi-infused spiritual politics, and sitar-soaked songs about drugs and lovemaking in the streets. The 1970s were no less bewildering: The decade that began with moratoriums against the war and the Weather Underground bombing ROTC buildings shattered into a hundred more esoteric pursuits, on the one end, and a slinking back into bourgeois life on the other. As founder of the Youth International Party (their candidate for president in 1968 was a pig ) and Chicago 7 defendant Jerry Rubin recalled, one day his phone just stopped ringing. He got a haircut, bought a suit, and became a stockbroker.

The poster—with its flower and its simple child-like observation—was a casualty of this cultural devastation. Politics was out, causes were out, idealism was out, caring was out, flowers were out. By the 1980s, if you wanted to get a quick if bitter laugh you only needed to recite the poster’s message in a supercilious voice, conjuring a whole cosmos of outdated hopes and dreams. “Peace and love” was the past. The future was money and finding ways to get it—even if that meant feminists joining the military-industrial-complex.

Only recently did I learn the story behind the poster. It started as a work of art. It was two-by-two inches, submitted to a competition in 1965. The judges thought it was trite. Its title was Primer. Soon after, a group of women was meeting in California. They were concerned that the anti-Vietnam War movement was being dismissed as composed entirely of fringe elements: guys in beards and sandals, leftists, radicals. They wanted to give voice to respectable Americans who opposed the war. Led by Barbara Avedon—a television writer who had written for The Donna Reed Show—they formed Another Mother for Peace. Their motto was “No mother is the enemy of another mother.”

We “wanted the Congress to know they were dealing with an awakening and enraged middle-class voters,” she later recalled. They decided to send Mother’s Day cards to Congress. “For my Mother’s Day gift this year I don’t want candy or flowers. I want an end to killing. We who have given life must be dedicated to preserving it.” Lorraine Schneider—the artist who had created Primer—agreed to let AMP use it on the card and other materials. It soon spread throughout the world.

Schneider was born in 1925 and grew up in the diverse immigrant neighborhood of Boyle Heights in Los Angeles. In the 1930s and 40s she was surrounded by Russians, Mexicans, Japanese (until Pearl Harbor), and her own Jewish community.

Her mother Eva was an artist also; she had come to America with her family to escape a pogrom in Ukraine. She later tried to contact her family left behind but “the whole shtetl was gone,” killed by the Nazis during one of their early extermination campaigns in the East. Lorraine grew up surrounded by her mother’s sculptures of mothers and children, and the stories of loved ones lost to war.

Primer nodded to her Ukrainian heritage with the prominent sunflower that stands next to the simple message. The flower seems to embody the qualities of the mothers in Eva’s sculptures: vigilant, protective, but very much mortal, just like the children and other living things that inhabit the places men turn into killing fields. Lorraine died of cancer in 1972, leaving a husband and four children behind.

Recently I was reading the prophet Isaiah. One translation has God chiding his people in language that could be ripped from today’s headlines: “Wicked nation!” God cries, “Destroyer of children!” Later Isaiah shares his vision of the world restored to innocence, with children and babies cavorting safely with lions and bears. “They will not hurt or destroy,” God promises, “on all my holy mountain.” Some commentators think it was this passage Paul had in mind when describing creation’s suffering in Romans 8, its yearning to be released from the consequences of men’s sins. Witnessing the horror of those consequences all the Holy Spirit can do is “sigh,” because even the Holy Spirit, says theologian N. T. Wright, is sometimes “lost for words.”

Whether the Holy Spirit is in fact speechless looking at what we do—the pogroms, the napalm, the bombs, missiles, barbarity, terrorism, callousness, starvation and all the rest—is, as they say, above my paygrade. But I know I am. So often I have no words, not to offer others, not to say within myself.

Maybe we need to start over, learning to speak again, with clarity and honesty. Without evasions like “casualties,” or euphemisms such as “collateral damage.” We need to learn how to name concrete truths about our world, and about ourselves. “War is not healthy for children and other living things” isn’t a bad place to start. Maybe that’s why she titled it Primer.

John H. Haas teaches U.S. history at Bethel University in Indiana