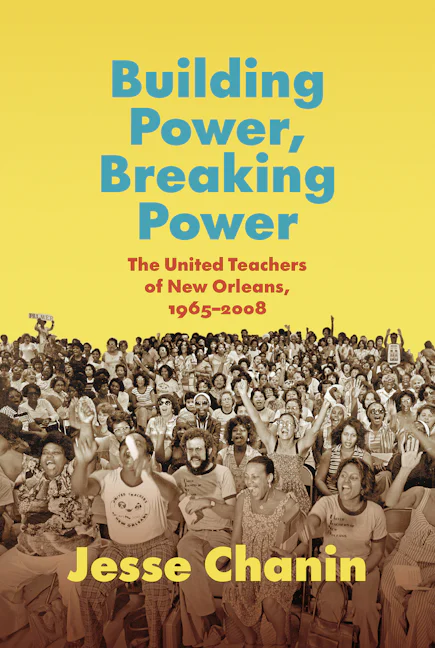

Jesse Chanin is a postdoctoral fellow at Tulane University’s Coalition for Compassionate Schools. This interview is based on her new book, Building Power, Breaking Power: The United Teachers of New Orleans, 1965-2008 (University of North Carolina Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write Building Power, Breaking Power?

JC: After teaching in a public school in New York City for five years, I was shocked by what I saw when I started working in New Orleans charter schools in 2013. In the schools I was in, I thought that both students and educators were treated poorly. I started to wonder about the impact of teachers unions (which I had taken for granted when I worked in the NYC schools) in protecting teachers and allowing them to do their best work.

When I started researching the United Teachers of New Orleans (UTNO), I was also surprised by how powerful and influential they had been. The post-Hurricane Katrina schools have been characterized by a lot of anger and sadness for people here, but I wanted to write a story that was not only about tragedy and loss. So I decided to focus on the union, which I think includes a hopeful story about what progressive organizing can look like in the South, and how that can occur when organizers work for racial justice and economic justice simultaneously.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Building Power, Breaking Power?

JC: UTNO achieved success by combining struggles for racial and economic justice and drawing on tactics and strategies from the civil rights movement (for example, participatory democracy and a reliance on strikes and protest). And secondly, the privatization-focused school reform movement is explicitly anti-union, anti-educator, and anti-Black; reformers intentionally eviscerated UTNO (and fired 7,500 educators) to create the all-charter district that we have today in New Orleans.

JF: Why do we need to read Building Power, Breaking Power?

JC: There is an urgent need to focus on the struggles of workers, especially workers of color, for rights and dignity in the South. We have seen how anti-democratic tactics and policies that prove successful in the South are then exported across the country. The charterization of the New Orleans public schools gives an example of this, laying clear the end goal of privatization within education nationally and the threats to democracy and workers that it presents.

At the same time, the book shows the potential of liberation struggles in the South as well. In the 1990s, UTNO was the largest local in Louisiana and wielded significant influence throughout the state—as a union comprised mostly of Black women. These stories should inspire us and remind us of what is possible, even amid oppressive political regimes.

Also, I think it’s just a very compelling story.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

JC: Though I received my PhD in Sociology, my dissertation, which became this book, ended up being quite historical. I think that it’s important to understand social phenomena in historical context, and the richness of that history can help sharpen our analysis. Looking back in time also helps us imagine other possibilities, alternative and liberatory paths that could have been taken—and maybe can still be taken today.

JF: What is your next project?

JC: I am currently doing youth participatory action research (YPAR) with middle school students in the New Orleans schools through the Coalition for Compassionate Schools. I am researching how elevating the perspectives of young people, and the data and stories they collect, can give us greater insights about how schools can better meet the needs of all students, especially those who have experienced trauma.

JF: Thanks, Jesse!