If George Whitefield was ‘America’s Spiritual Founding Father,’ the road ahead was bound to be rough

This essay is a Preview, an occasional feature at Current and a companion to our Review features. In Previews we publish short excerpts from new and upcoming books that tell a good story and fit our general mission of commentary, reflection, judgment. This essay has been adapted with permission from the publisher from Ownership: The Evangelical Legacy of Slavery in Edwards, Wesley, and Whitefield. Intervarsity Press, 2024. 240 pp., $18.00

***

On September 30, 2020, I spoke at Old South Presbyterian Church in Newburyport, Massachusetts, at a memorial for a man who never knew me. But I knew him.

George Whitefield died on that day, 250 years before, and his body is buried in a crypt below the church. Tom Schwanda, a theologian from Wheaton College, Mark Noll, a historian from Notre Dame, and I spoke at a (virtual) worship service to commemorate Whitefield’s life, legacy, and ministry. The event organizers had invited me to speak on one of Whitefield’s favorite topics: the new birth.

The event went well. I gave my talk, then returned to my other commitments. A month later, I received an unexpected package in the mail. It included a generous thank-you note from the church and a gift. I opened the small package with curiosity and was surprised to find a coin. The church had minted a commemorative coin for the occasion of the 250th anniversary of Whitefield’s death.

One side of the coin was embossed with the words Rev. George Whitefield over a portrait of Whitefield’s characteristic round face and crossed left eye. He is wearing his minister’s wig, robe, and preaching bands—the classic image of Whitefield.

On the other side of the coin, the outer ring stated, America’s Spiritual Founding Father. This declaration about Whitefield is common among secular and Christian historians of early America, and as we will see, its truth is both inspiring and chilling. But it was what was written in the middle of that side of the coin in small font that caught my attention. It was from a letter Whitefield wrote on July 12, 1749:

I am content to wait till the day of judgment for the clearing up of my character: and after I am dead, I desire no other epitaph than this, “Here lies G. W. What sort of a man he was, the great day will discover.”

One of the reasons Whitefield’s words caught my attention was that two months before the memorial, on July 2, 2020, the University of Pennsylvania decided to remove a statue of Whitefield that had been standing on the campus for over a hundred years. “In 2006 and and again in 2016 the university denied having any connections to the institution of slavery,” writes VanJessica Gladney, who with a team of researchers presented Whitefield’s enslavement of Black people and his successful efforts to legalize slavery in Georgia. The University of Pennsylvania revisited “what sort of a man” Whitefield was and came to their own conclusion. Whitefield may have been waiting for God’s judgment, but the University of Pennsylvania made their judgment much sooner.

Few Christians, if any, doubt Whitefield’s genuine faith in Jesus Christ. Yet many admirers have come to doubt aspects of “America’s Spiritual Founding Father’s” character—myself included. Still, 250 years ago, at Whitefield’s official memorial, one of his closest friends, John Wesley, didn’t publicize the doubts that the University of Pennsylvania and I have about his character.

The organizers at Old South Presbyterian Church addressed Whitefield’s checkered legacy in their 250th memorial of his death. They titled the several-months-long series of events “The Great Awakening Meets a Just Awakening.” This memorial was quite different from the one John Wesley spoke at shortly after Whitefield’s death. As we’ll see, this funeral was a pivotal moment in evangelical history regarding slavery. Old South Presbyterian Church designed their events to acknowledge the “gap between the inclusive gospel message that Whitefield preached and his devastating failure to embrace the full personhood of African Americans.” I was proud to be part of a series of events to admire the strengths of Whitefield while also acknowledging the harm he brought to the people he enslaved, the people of the state of Georgia, and so many others. The man who proclaimed the gospel of liberty from slavery to sin held Jeremy, Abraham, Abigail, Fanny, and forty-five other people as slaves to him—and upon his death gave all of them to his top financial donor.

I meet admirers of Whitefield who don’t know about his slaveholding or about his political and doctrinal support for its legality. I am quick to educate them on these details. Yet education is not enough. James Baldwin writes, “History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.”

The work of historical retrieval is, in a way, the easy part. The hard part is choosing how I will navigate, and own, what happens in my country, in my state, in my city, in my neighborhood, and in my home—today.

Few Americans are naive enough to think that slavery is irrelevant to our present condition. We recognize that personal and systemic race-based inequalities, beliefs, and experiences persist—these are not issues relegated to the past. While most modern Americans reject the ideology that supported slavery, some American Christians champion the history of American slavery as idyllic.

In 1996, Idaho-based pastors Doug Wilson and Steve Wilkins authored a short book titled Southern Slavery: As It Was. In their introduction, they wrote, “Southern slavery is open to criticism because it did not follow the biblical pattern at every point.” Regarding Southern slavery, they write, “There has never been a multi-racial society that has existed with such mutual intimacy and harmony in the history of the world.” They go on to claim that “slavery produced in the South a genuine affection between the races that we believe we can say has never existed in any nation before the [Civil] War or since”. These pastors, promoted by prominent evangelical media outlets, illustrated that slavery is not an issue of the past. In their view, slavery is an ideal social system to aspire to in the present, if done in the way they think aligns with the Bible.

When a 2020 Twitter post revived the opinion of Wilson and Wilkins, Wilson responded on his blog that he stands by the general premises of his initial claim. He added, “The problems [with slavery] became more pronounced as things moved toward the Civil War—e.g., slavery in Jonathan Edwards’s day in New England was not the same sort of thing as slavery in Alabama in 1850.” Wilson’s focus is on how to enslave people in a way that aligns with the Bible, rather than on an outright denunciation of the institution.

John MacArthur has pastored Grace Community Church in Los Angeles since 1969. He leads The Master’s University, The Master’s Seminary, and the international radio ministry Grace to You, and is the author and editor of over one hundred books. MacArthur teaches that Christians should revive a biblical understanding of the institution of slavery and put it into practice today. He explains:

[It is] strange that we have such an aversion to slavery because historically there have been abuses. . . . For many people, poor people, perhaps people who weren’t educated, perhaps people who had no other opportunity, working for a gentle, caring, loving master was the best of all possible worlds. . . . Slavery is not objectionable if you have the right master. It’s the perfect scenario. [Cited by Rick Pidcock.]

MacArthur believes that slavery is a part of “the best of all possible worlds” and “the perfect scenario” because, as he writes, “neither the Old nor New Testaments condemns slavery as such. Social strata are recognized and even designed by God for man’s good.” MacArthur celebrates that “the back of the black slave trade was broken in Europe and America due largely to the powerful, Spirit-led preaching of such men as John Wesley and George Whitefield.”

MacArthur’s understanding of Wesley and Whitefield’s role in the history of slavery is shallow and misguided, to say the least. MacArthur denounces how to enslave people—he is against the “black slave trade”—but believes that the institution of enslaving people is “best,” “perfect,” and “designed by God for man’s good.” New Testament scholar Esau McCaulley explains that slaveholders of the antebellum South maintained that the two options were “biblical slavery versus bad slavery. The problem was not slavery itself.”

While Wilson’s, Wilkins’s, and MacArthur’s views might represent a fringe opinion among American Christians, few modern people are looking to any White Christians to guide society in the right direction regarding race relations. Many people do not trust that White evangelical Christians have learned from their past. James Baldwin explains, “To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used; it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought.” Evangelical Christians like me can learn to use our past when we rightly understand the cold facts of our failures alongside the truths of our triumphs. Learning from the past can help us confront modern slavery directly (e.g., human trafficking, forced prostitution, forced labor, forced marriage) as well as learning how and when to be constructively critical of secular and Christian cultural assumptions in our world today.

____________________________________________________________________________

Taken from Ownership by Sean McGever. ©2024 by Sean McGever. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press. www.ivpress.com.

Sean McGever (PhD, University of Aberdeen) is an area director for Young Life in Phoenix, Arizona, and adjunct faculty at Grand Canyon University. He is the author of several books, including Born Again: The Evangelical Theology of Conversion in John Wesley and George Whitefield and Evangelism: For the Care of Souls.

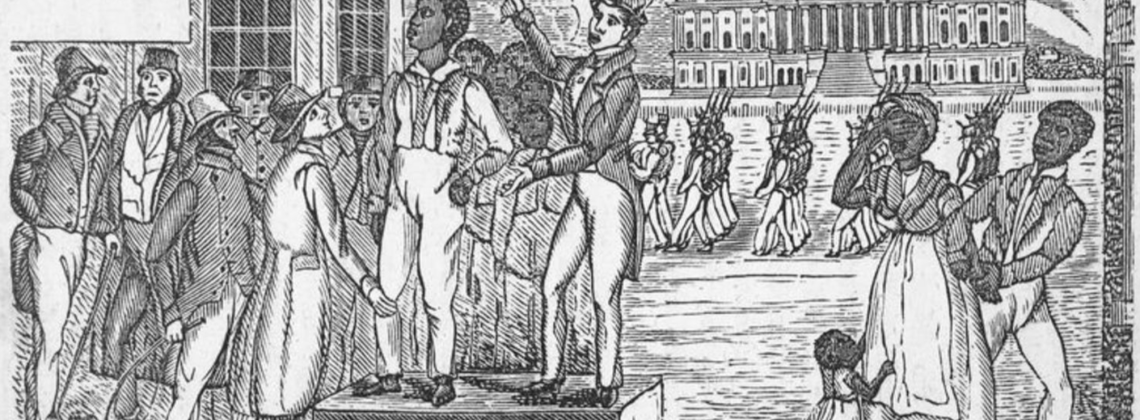

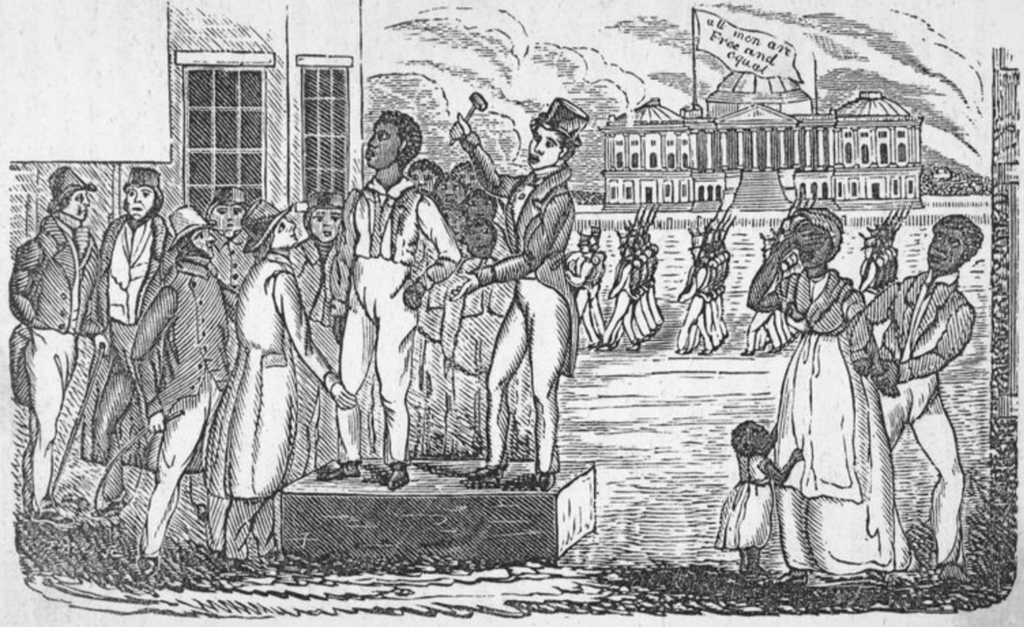

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Nice.